Does anybody in Hawke’s Bay make money? Sure, everybody who holds a job ‘makes money’, but how many earn more than enough to just make ends meet? And what about the businesses they own or work for? How many are profitable enough to fuel expansion?

Does anybody in Hawke’s Bay make money? Sure, everybody who holds a job ‘makes money’, but how many earn more than enough to just make ends meet? And what about the businesses they own or work for? How many are profitable enough to fuel expansion?

The backbone of the Hawke’s Bay economy is primary production; growing sheep and cattle, fruit and veggies, grapes and trees. And (largely) exporting those as raw commodities or, with added value, processed consumables. Growing and processing stuff, and servicing those that do, accounts for as much as 40% of the region’s economy. Yet when one reads or hears accounts of the sector’s fortunes, the picture is one of dire straits. Farmers are drowning in debt, unreliable water supplies, depleting soils, uncooperative weather, less stock, biosecurity threats, high production costs, profit-killing exchange rates and overseas consumers becoming more demanding. Other than the increased agricultural production assumed from new irrigation schemes, few point to the ag sector as one promising dynamic growth for the region’s economy. Many workers in the sector receive relatively low wages while others are only seasonally employed, if they can get work at all, considering the recent loss of 300 boning plant jobs in Waipukurau.

Then there’s tourism which accounts for another 5-10% of our region’s economy. Local media and council papers routinely discuss the politics of who’s in charge of Hawke’s Bay tourism, who or what is to blame for stagnant (at best) visitor numbers; strategies for improving ‘bed nights’ by some infinitesimal number, and how much the industry should be subsidised by ratepayers. This is another sector where it seems, only the lucky few businesses – mostly catering to high-income visitors – actually make money, and which pays mainly low wages, reflecting low skills.

Then there’s the rest of the Hawke’s Bay economy; say 50%, quietly doing other stuff and mostly operating under the radar. Maybe they’re the ones making money without council subsidies of one sort or another? Maybe they’re the ones who pay higher incomes? Maybe they’re the ones who actually represent the region’s economic growth potential – on a sustainable basis – for the future? Does Hawke’s Bay in fact have two economies; one struggling to keep its head above water — the other quietly vibrant?

Regional economic profile

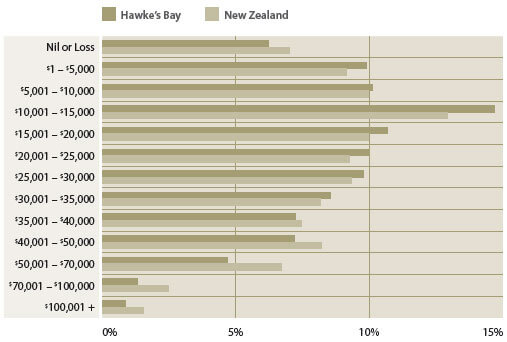

The official statistics remind us regularly that Hawke’s Bay is a laggard region economically. We have the third-lowest value regional economy, measured by GDP. We lost more jobs in the last year than any other region. And we have the third lowest incomes. As Hawke’s Bay Chamber of Commerce CEO Murray Douglas notes: “This is a persistent issue over many years, where we lag New Zealand in good times and have an inferior outcome in bad years.” (See Figure 1 for the basic structure of the Hawke’s Bay economy by sector).

Our present line-up of economic activity produces a lower income profile relative to the rest of New Zealand. While the median personal income (for people age 15 and over) across the country is $24,400, for Hawke’s Bay it is $22,600, just above Manawatu-Wanganui ($21,600) and Northland ($20,900). There’s little reason on the surface to expect significant improvement, given the sectors that presently dominate and the adverse population trends that lie before us. Overall, Hawke’s Bay’s population is projected to grow by only 3,500 in the next 20 years; hardly a runaway engine driving economic growth. Our percentage of ‘non-productive’ residents (in income-producing terms) will grow sharply as the Bay’s population ages. Nationally the median personal income of those 65 plus is $15,500. Meanwhile, the highest growth in working-age population will come from our Mãori segment, which presently has the lowest incomes, skills and education. The median personal income for Mãori in Hawke’s Bay in 2006 was $19,200. Of those employed, 35% were aged 15 and over and work as labourers; 45% of local Mãori aged 15 and over had no formal education qualifications.

A further reality is that the typical wages associated with industry sectors that dominate our economy are generally low. If one assumes that the benefit of growth is generating higher incomes for our population, it would follow that any strategy for economic growth in Hawke’s Bay must address these fundamental structural realities. Not to do so is effectively choosing to remain poor.

Our alternative economy

No one disputes that any near term strategy to improve our region’s economic performance must begin with extracting more (but sustainable) productivity from our land and water resources. Every ‘official’ discussion of economic development in Hawke’s Bay begins from that premise. The Chamber’s Murray Douglas writes: “With some partnering through our tertiary institutions, some key skill development and some fine tuned investment, we can be more confident about building up the quantity and quality of our agri-food and rural support processes.” Hawke’s Bay has unique IT and engineering skills associated with fruit handling systems, innovative packaging and other food technologies. In the right environment, he says these “can be leveraged into the global market”.

As Michael Bassett-Foss, Hawke’s Bay Regional Council’s economic development manager, puts it, “the economic power is on the fringes of the momentum already created by primary production.” The implicit point is that not all activities associated with the primary sector are low wage, and our farm output need not be satisfied to earn commodity-based revenue. The HBRC has just updated its regional economic development strategy, with input from a wide array of stakeholders. The resulting document says: “CRIs, central government agencies and universities are keen to be involved in implementing science in the primary sector, assisting with commercialisation and export growth – this is an area that has been lacking in Hawke’s Bay.” And: “Continued innovation and productivity improvements such as livestock genetics, water management and bio initiatives have allowed further on-farm gains to be introduced, although there are barriers to getting uptake of these improvements.”

By far the largest local government infrastructure investment under consideration in Hawke’s Bay – potentially involving more than $200 million – is a series of water storage and irrigation schemes. There’s no question where HBRC is looking to place its economic development bet. The second largest local government ‘bet’ is being made on behalf of the region’s tourism sector. The most visible investment is the regional council’s grant of $2.55 million over the next three years to Hawke’s Bay Tourism, the region’s new tourism promotion agency. But that amount will be matched – and more – by funds spent by Hastings and Napier councils promoting their own identities and attractions. But Murray Douglas argues, leaving aside the inherent dysfunction of a multi-headed tourism promotion effort, tourism “… on its own is simply the ‘hotel on the farm’ concept – useful but not a hugely productive investment for Hawke’s Bay’s future.”

At the most recent gathering of the HBRC’s stakeholder group, an interesting mini-debate occurred, with some asking for even more emphasis on boosting the primary sector, while others were looking for a different emphasis looking to the future. The latter view, because it is newly emerging, was not as clearly articulated. It revolves around building or attracting ‘knowledge-based’ businesses and the individual entrepreneurs and more educated technical workers and professionals associated with such businesses. Many of these people are assumed to be younger, helping to fill the Bay’s ranks of 30-50 year-old peak earners.

Sir Paul Callaghan, a much-honoured scientist and Kiwibank’s New Zealander of the Year, argues that New Zealand needs to focus its growth aspirations on entrepreneurial companies looking to fill small technology niches. He identifies ten such companies that presently have export sales of nearly $4 billion … and asks why not 100 such companies? Leading BayBuzz to ask … why not more of those in Hawke’s Bay? Our region typifies what Callaghan argues is the wrong path – stubborn emphasis on primary production and tourism. The HBRC’s strategy paper, while solidly behind the primary and tourism sectors, at least nods at the importance of diversification, saying: “Hawke’s Bay is inappropriately perceived as a location with limited economic opportunities outside of its core industries of agriculture and food processing. There is business diversity although more is needed.”

A campaign is proposed to “build on our centres of excellence and target new innovative industries to diversify our economic base”. This campaign would include tapping the region’s expat community to recruit businesses, entrepreneurs and investors; co-odinating ‘red carpet’ treatment for businesses considering moving into the Bay and leveraging the broadband deployment now occurring, to attract knowledge-based businesses. Of course, Hawke’s Bay already has many companies like these, congregated around software, IT, communications and marketing/advertising, applied engineering, and niche technologies. These businesses are staffed with higher earning, well-educated professionals and high-skill technicians. However, they are generally tiny, and their growth potential lies in exporting their services far beyond Hawke’s Bay. In theory at least they are perfectly positioned to do this, since they are chiefly selling highly scalable brainpower and ‘lightweight’ components (low weight relative to value).

Former Saatchi & Saatchi New Zealand chief executive and Bay resident Kim Wicksteed says: “These people are very dynamic and intelligent. They need to network and increase their visibility … they could well give us a competitive edge.” Bassett-Foss refers to this as ‘clustering’ – excitement and momentum begets more of the same. As BayBuzz sees it, once organised, this cluster should seek to influence the direction of Hawke’s Bay no less than Federated Farmers or HB Fruitgrowers or the sports fraternity.

Attracting companies and workers like these – businesses and people who could locate anywhere – requires delivering a lifestyle and amenities that can compete respectably against our urban centres. The creative and cultural community contributes importantly to the ethos necessary to attract more cosmopolitan (and maybe more energetic?) migrants. As Kim Wicksteed notes: “These people are young, vibrant, up-to-date…they are Hawke’s Bay’s future.” They enrich the social fabric of Hawke’s Bay, adds Bassett-Foss. “But these educated, skilled people, and their spouses, need more than a job, good schools, good lifestyle and climate; they need culture, entertainment, and excitement.” He talks of marrying business and social diversity. Localising the refrain of Paul Callaghan: We need to build the Hawke’s Bay where talent wants to live.

Hawke’s Bay’s Mãori economy

The younger rising professionals we are just talking about might as well be on another planet, when compared to another key group in Hawke’s Bay to be reckoned with.Half of Hawke’s Bay’s Mãori population is under age 23; 36% are under the age of 15. As noted earlier, of those employed, approximately 35% of those age 15 and over are labourers and 45% have no formal education qualifications. Is this a group consigned to provide low wage labour forever, staffing the Bay’s fast food outlets and fields? A permanent under-class? If so, this is the income distribution that will persist. Some powers-that-be, talk about a sort of ‘demand-pull’ solution. If we irrigate enough, and grow more stuff, we can process more stuff and there will be more jobs to fill that demand higher skills and pay better. But is that more than theory or wishful thinking?

The recent announcement by Heinz Watties that it was shifting significant food processing business to Hastings doesn’t offer much hope. According to chief operating officer Michael Gibson, while a small number of new positions will be created, “the Hastings facilities have the infrastructure to absorb the additional volumes into current operations.” Murray Douglas notes that young Mãori could represent fully half the Bay’s entire workforce by 2021. He says the primary production jobs “will always be here in Hawke’s Bay”, and expresses hope that ten years is enough to improve education and training opportunities.

However, it’s not at all clear who might drive an initiative to up-skill young Mãori or present them with opportunities greater than those available to their parents. Jason Fox, chair of Hawke’s Bay’s Mãori Business Network, says that role modelling is critical. He’s advocating a physical centre that would bring together the best Mãori minds in the region into one place, where they would be far more visible. “The alternatives need to be easy to see” for young Mãori. Not that he has anything against teachers, lawyers and accountants, Fox hopes more of the smartest kids can be enticed into business. Beyond that, he suggests that more Mãori need to move from the ‘employed’ to the ‘self-employed’ mindset, starting their own micro-businesses, like most of the existing 130 businesses in the HB Mãori Business Network.

Nationally, the Mãori economy is estimated to be worth $37 billion. Mãori enterprises generate about 8% of our income and account for $9.5 billion in assets (all figures from BERL). But there’s little evidence of that wealth in Hawke’s Bay. Local Treaty claimant groups will receive an estimated $300 million compensation. How those funds might be used to uplift the skills, competencies and aspirations of young Mãori in Hawke’s Bay is, well, a million dollar question.

Paths to explore

Effectively maintaining the economic status quo in Hawke’s Bay is choosing to be poor. While healthy ‘debate’ might occur between those wanting more focus on the primary sector and those advocating more diversification, one thing is crystal clear, changes are required. Distilling from the debate, here are some paths forward.

Improve agricultural productivity and profitability

Many observers believe that significantly more income can be generated by the Bay’s primary sector. Says local economist Sean Bevin: “We can’t dismiss the natural advantages we have, those are unchanging; but we must generate a greater economic return from them… Not enough thought has gone into product development and marketing.” In theory, it’s simply a matter of adopting best practices to improve productivity, applying technology to add value, and better marketing the end product. Nice aspiration, but where will the leadership come from to bring more ag science into the Bay, and then get slow-moving (and aging) farmers to embrace it?

Some growers in the Bay believe the challenge is in smarter positioning and marketing of our produce as pure and premium, including ‘GE free’. John Bostock of Pure Hawke’s Bay advances that view elsewhere in this issue.

Expand the Bay’s technology sector Sir Paul Callaghan says New Zealand needs to deploy its human capital against far more lucrative enterprises than primary production and tourism. Tourism, he notes, generates around $80,000 in revenue per job. Just to maintain our current GDP, each job must generate $125,000. Fisher and Paykel Healthcare, with $500 million in exports, generates $232,000 per job. To Callaghan, it’s all a matter of deploying human capital against the most productive sectors, which he expects will be niche technologies. We don’t have a Fisher and Paykel Healthcare in Hawke’s Bay, yet. However, we do have tech-based firms that fabricate and manufacture — and export beyond the Bay; precision electronic controls, restaurant fittings, software, welding components and frost protection windmills, to name a few.

Educational leadership

The strategy advocated by Callaghan assumes educational priorities that motivate and develop the skills that match up against the high value opportunities. EIT and our high schools are key players in any Hawke’s Bay economic development strategy. “They need to be leaders in this debate,” says Murray Douglas, who worries about future workforce capabilities. Callaghan mentions three steps that seem relevant for our region’s education leadership; get kids and teachers visiting the smart businesses, significantly boost science and mathematics education, and build school programmes in entrepreneurship.

Everybody must export

So obvious, but sometimes overlooked as a challenge to ‘growing the Bay’, is our tiny market size. If a business really wants to make money, it needs to export outside the region and outside the country. Murray Douglas would like to see Hawke’s Bay ‘embassies’ in Auckland and Sydney. “Every single business in Hawke’s Bay must be an exporter…selling in Taupo, Auckland, Sydney and Shanghai.” There’s an aspiration! And we have businesses that do it. Like Furnware, ABC Software, Southern Lights Ventures, Future Products Group, Blue70. Most Hawke’s Bay consumers have never heard of these businesses, precisely because they are focused on exporting their goods and services and quietly returning wealth to our region.

Who will lead regional economic growth?

Local politicians can provide critical infrastructure; allocate land and water; subsidise this or that industry; market the region as a whole to visitors, investors and outside businesses. They can lobby for central government largesse and coordinate region-wide amenities like cycle ways. Local education leaders and institutions can study and help us understand our regional economy and its many sectors, prepare young people to be competent in whatever role they aspire to, provide more occupation-specific training, and by their reputation for excellence, help attract migrants. The business community, including agri-business, is the engine. Individual entrepreneurs, some world-class, create enterprises and generate jobs across all sectors. However, they can compete against one another commercially, thereby complicating collaboration for the ‘greater good’ of Hawke’s Bay.

Collaboration is an essential ingredient for creating the tide that lifts all boats. The Bay is too small and resource-thin to duplicate efforts to promote itself to the outside world as ‘the place to be’. Similarly, collaboration is needed to focus responsibility for other initiatives within the Bay; building infrastructure, identifying and meeting training needs and networking within sectors, to strengthen our competitive advantage. Business Hawke’s Bay offers a new structure, potentially, for much of the business community to coalesce around common growth objectives, and then to collaborate with local government, iwi and education, who bring their own perspectives and responsibilities for achieving them.

Murray Douglas, shepherding the Business HB initiative, sees it as a way to capitalise on the Bay’s most accomplished entrepreneurs, who can help entice others to the Hawke’s Bay party. “We need to much better harness the energy of people in the Bay who have done it, like Ray McKimm and Robert Darroch. That’s one of the strategies Business Hawke’s Bay will pursue.” Ultimately, any economic growth for the region must occur within a broader framework of sustainability and social equity. That framework, and any ratepayer investment in economic development, must be determined and overseen by our local elected leaders. As for our elected leaders, perhaps the greatest contribution they might make toward advancing Hawke’s Bay’s prospects would be unification, which deserves to be fully explored. And soon

Hi Tom, I came across this article and wonder if you think we are still ‘Choosing to be Poor’ have you considered this argument since?