The election noise is thankfully over. Time to settle back into three more years of ‘head down, bum up’ ongoing work. One of the projects keeping our public servants busy is the review of the Hastings District Plan.

Development rulebook

The District Plan (DP) is a document legally required by the Local Government Act to define the nature of development for a district or city council. In essence, it is a set of rules dictating what we can and cannot do as of right in our backyard. It sets trigger points for council involvement via resource consent processes, as well as defining good practice and criteria for assessment.

“The Hastings District Plan provides the means for the people of the Hastings District to manage the effects of the use, development and protection of the natural and physical resources within the Hastings District. It guides and controls how land is used, developed or protected in order to avoid or lessen the impact of any adverse effects.”

By law every statutory authority must have a DP and must review it every ten years to make sure development rules remain current, are reflective of community aspirations, as well as allowing for a sufficient land supply for both residential and commercial/ industrial activity, economic development and employment growth.

It is an opportunity to integrate strategic vision and community aspiration in a statutory document.

The review process

A draft version of the revised DP was presented in meetings around the district in April into June. 312 submissions were received and public presentations to a hearing committee were encouraged. Comments were taken on board where council officers saw merit and each submitter was entitled to a written response.

“As a draft, the Plan has no legal status under the Resource Management Act. The reason for releasing a draft, is to give the community a feel for the direction that the Council is proposing to take in its review, and provide an opportunity to comment on an informal basis.”

A daunting piece of work on all accounts, but a box has been ticked and the process has moved a step closer to becoming law.

The ‘official’ draft DP will soon be notified with all revisions based on informal comments in place. The public will then have the chance to make formal comments on the document and go through a formal hearings process.

The timeframe for comments is 9 November through 14 February, just in time for some holiday reading. Any aspects of the plan that are not submitted on become operative by default. A process follows where submissions are reviewed, a few more boxes are ticked, and – presto – the District development direction is cemented for the next ten years.

Development is the word

The draft DP is no lightweight bedside reading! It’s a copious volume of policy and rules focused on what is and isn’t allowed in our built environment, compressed into a whopping 1,088 pages.

That’s too much to examine in any detail in this article. Instead, I will try to highlight from my point of view – as a Hawke’s Bay-based, internationally trained, urban designer – some of the key areas of change worthy of consideration, scrutiny and applause, as appropriate.

To get a taste of the draft DP, I conducted a word search to identify some of the key focus areas in the document.

The prize for most used word goes to ‘development’ – 2,372 instances, which rightly confirms that the theme of the plan is district development! No rocket science there.

The word ‘amenity’ is counted 1,071 times – the counter to development and a key concern of the plan and those authoring it.

The balance between development and amenity is what the document, in the end, is charged with brokering. This in itself highlights a fundamental conundrum. Development and amenity have a strained relationship at the best of times – control versus the free market, rules versus freedom, the opinion of technocrats versus individual taste, and of course, the right of the individual versus the greater good.

Other notable words include: manage (1,039), design (873), parking (722), quality (252), mitigate (229), control (233), density (212), sustainable (210), urban design (128), and fences (135).

Some interesting ‘laggards’ include: balance (62), versatile soils (49), architecture (6), and productive soils (5).

New directions

For the last thirty years, the district has had a ‘one size fits all’ system for controlling residential development in urban areas – an ‘any development is good development’ approach that is past its use-by date. The same rules have been applied to a residential property whether in Central Hastings, Havelock North or Flaxmere. That is about to change significantly.

A new regime of residential zoning rules is been launched, the objective of which is:

“To enable residential growth in Hastings by providing for suitable intensification of housing in appropriate locations.”

However, the horse has already bolted on unsuitable infill, which has conspired to destroy the garden city aspect of the district over the last thirty years. It is difficult to find a street in Hastings that hasn’t been peppered with infill to the benefit of a baby boomer’s retirement fund. Low minimum site requirements of 350 m2 have allowed for some fairly high density, low amenity areas to develop.

Density of housing development is measured in Dwellings per Hectare (DPH). Traditional pavlova paradise has been around 12-14 DPH, but infill development under current rules has allowed up to 28 DPH.

Infill development is an issue much bigger than the Hastings district; it is at the core of a national debate around housing affordability and Kiwis’ cultural attitudes to property and housing. ‘Urban intensification’ is also an issue of national scale. A term that has caused much nimbyism, political wrangling, closed door dealings and PR billings.

Aiming to solve issues of national significance is optimistic at best for a district the size of Hastings. Shouldn’t issues of national scale be left to central government to solve, leaving local government to get on with what they are best at? We have national standards for all kinds of things, why not design?

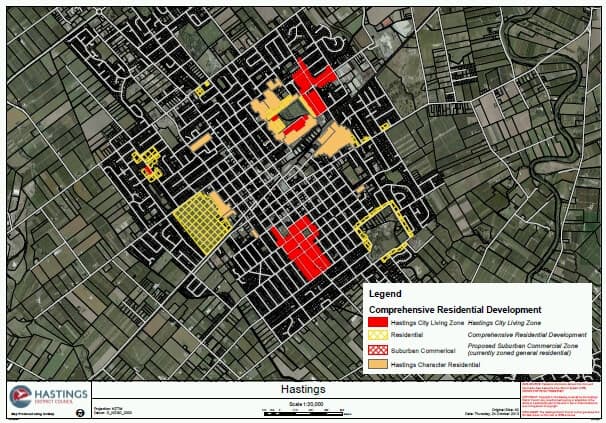

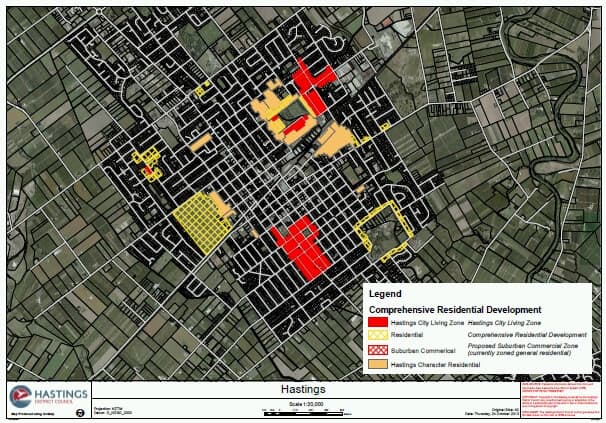

So now, perhaps thirty years too late for Hastings, rules are about to be put in place redefining what ‘character’ is and what you can or can’t build where. The District Plan review has thankfully highlighted the need to maintain ‘character’ in certain areas of Havelock North and Hastings and has established specific zones of residential character.

Hastings has 13 proposed Character areas to which varying degrees of protection apply. They have been identified based on technical reports and consultant feedback and are generally interested in maintaining pre-1950s character.

Alongside and overlapping with areas of character are two other new zones affecting residential development – the City Living zone and Comprehensive Residential zone. A general residential zone remains in place, but minimum lot sizes increase from 350m2 to 400m2.

Planned intensification

Driven by the regional policy statement (RPS 4) and the Heretaunga Plains Urban Development Strategy (HPUDS), the DP review has come to the party to lay the groundwork for a housing intensification programme.

“‘Planned intensification’, to assist with meeting future demand for housing in Hastings is to be provided for.”

In the name of protecting the precious soils, a regional push to counter sprawl has predicated areas where higher density suburbs could be developed. This current District Plan review has taken the opportunity to put some detail into HPUDS to allow for ‘strategic’ implementation of policy and roll out in those HPUDS-specified areas. Some have been deferred, such as Haumoana/Te Awanga; some have been largely ignored, such as Hastings CBD; and others have been given a clear green light, like Mahora.

The choice of areas for intensification has been based on proximity to commercial zones, proximity to parks, as well as capacity of existing infrastructure to cope with increased loads.

Predictions on future demand are based on Statistics NZ data and a range of growth scenarios. Figures just released indicate Hastings District has grown only 5,820 residents since 2001 (from 67,425 to 73,245), or only 0.7% per year (485 people). The HPUDS assumption is a growth of 6.3% or 8,255 new Hawke’s Bay arrivals in the period 2015 of to 2045.

Creating density

A Comprehensive Residential Zone has been created to enable what it suggests:

“Comprehensive Residential Development’, where multiple residential units are planned in an integrated way and enable better amenity.”

Minimum lot sizes (250m2 per residential dwelling, or 40 DPH) are prescribed for comprehensive development to occur. The premise is that multiple sites could be purchased to create a super site (minimum 1400 m2) of enough scale to predicate an integrated development approach much like townhouses of yesteryear.

Assessment criteria have been proposed for projects in this zone including “Whether the development is an appropriate architectural quality, is aesthetically pleasing and contributes positively to the surrounding area.” Site orientation and project utilisation of passive solar capacity is one forward-thinking criteria introduced in this zone.

Methods for evaluation are not outlined, but there are many models to draw on. Urban designers and urban design panels are a valuable resource to other councils in this respect. It will be interesting to see how the council’s own development on Fitzroy Avenue will stand up to the new assessment criteria of “appropriate” quality, without being vetted for design quality.

“Comprehensive Residential Development can occur subject to meeting assessment criteria and evaluation to ensure it is designed to carefully fit in and respect the particular characteristics of that area.”

The City Living Zones are based on the idea of sites closer to the inner city being more suitable to higher density living. The zoned areas are located in close proximity to Mahora shops and Cornwall Park, and around local shops on Heretaunga Street East and the open space of Queens Square and are tagged to provide more choice than what the current market provides. Proposed site areas are 250m² average minimum with a maximum site size of 350 m².

“The City Living Zone is essential to the successful implementation of HPUDS in achieving a more compact urban area.”

These new residential zones sit in uneasy alliance. The premise of intensification around parks, especially Cornwall Park and Queens Park, is somewhat at odds with the retention of character.

Minimum site sizes are required for the comprehensive model, which will mean developers need multiple sites cleared to create a higher density product. This seems to pose a threat to the character of the area being developed. Will the assessment criteria and method of assessment be robust enough to prevent this from happening?

There is a risk the amenity of some character zones around parks will be compromised. The plan is trying to protect with one hand, while allowing an untested model with the other. That is the planner’s conundrum. Developers’ yields would potentially double, with no clear process for targeting development contributions back into the affected community. Meanwhile, existing public amenity can be seen as adding value to the developer’s project. Not a bad deal.

Higher density living definitely requires greater access to parks and public space than the ‘garden city’ model. However, this does not mean higher density housing should be located near existing parks and high public amenity areas. There is potentially a recipe for compromise.

Generally, intensification is targeted in areas with transport and commercial nodes or along arterials, with large brownfield sites prioritized. Developers should be compelled to provide quality public space as part of their planning, placing the responsibility for amenity on developers rather than the community.

Compact cities with a high regard for design and public space are by necessity the way of the future and the council should be applauded for taking this approach. The difficulty arises in ensuring quality. A medium density design guide is in the works; it will be interesting to see how it adds detail to the DP once published.

We need not approach urban intensification naively; rather we should take aboard the options, research and best practice examples and mistakes of the last thirty years. Ultimately the DP provides a great opportunity for the region to lead.

We need to be sure there is robust discussion and understanding of the issues the DP sets out to address in its proposed re-jigging of residential development rules, and that the idealism inherent in the planning profession comes to the fore providing the means for the people of the Hastings District to manage the effects of land use, and development.