Hawke’s Bay is a food basket of New Zealand. Down most of our rural arterials you will find roadside fruit and vege shops. We have bustling farmers’ markets. We produce milk and honey, meat and eggs. For those who know how to fish it up there’s white bait in our rivers and kahawai in our bay. But every day there are children in Hawke’s Bay going hungry.

Receiving much publicity nationwide is KidsCan’s mission to feed all those children who need food in low decile schools. Alongside this is Labour leader David Shearer’s ambitious plan to feed all children in all low-decile schools (primary and intermediate) whether they need it (want it) or not.

So, what is the situation in Hawke’s Bay? How many children need more food than they’re getting at home?

And, can we, in the Fruit Bowl of New Zealand, fix the problem?

Mouths to feed

First, the numbers: Often quoted are the 230,000 children across New Zealand who fall below the poverty line. Focus in: There are 35,880 children (those under 15) living in Hawke’s Bay. Of those, statistically, 20% fall below the poverty line, that’s over 7,000. In terms of the food debate, 9,000 Hawke’s Bay children attend low-decile primary and intermediate schools.

KidsCan is the national organisation that has taken on the task of feeding hungry kids through schools. The charity works with over 200 schools nationwide and has another 100 on its waiting list.

Julie Chapman is KidsCan’s chief executive: “We operate on an estimate of one in every ten children in low-decile schools require our help.” But in reality Chapman believes the rate is higher.

“I would suggest it’s probably more like one child in every five or six needs assistance.”

In Hawke’s Bay that means 900 children at a conservative guesstimate. But the number could be as high as 1800. KidsCan is currently feeding 120 Hawke’s Bay children every school day.

“We provide a framework and it’s not a cookie cutter approach. Some schools have a kai basket, some have food available for children in the office, some do lunch box checks and top up food from that point,” says Chapman.

Chapman also explains that a few schools don’t want to be charged with feeding their students. “Some schools don’t feel they can fill that role. Some principals don’t want to feed their kids, they don’t see that as part of their job.”

Hungry Hawk’s Bay

KidsCan currently supplies food to 14 schools in our region, one of those is Flaxmere Primary.

Principal Robyn Isaacson says the school uses KidsCan contributions in its existing schemes such as its breakfast club. In the decile 1a school with its roll of 462, about 10-12 children a day access the programme and the school keeps a list of who attends. In that way they can monitor who is requiring food and how often. If there are concerns, a social worker connected to the school makes contact with the family.

“I have never struck a parent who doesn’t care,” says Isaacson. “It is other factors at play. In the minority of cases it may be issues with budgeting, and sometimes we are talking about quite big families with lots of children of different ages.”

Providing a meal at school also helps teach children what good nutrition means, and it helps build a foundation of healthy eating through life and making good choices about food.

“Breakfast is a really social time here,” says Isaacson. “We put out table cloths and cutlery, we do it properly. The kids enjoy the social interaction. And fundamentally they need to know that we care enough to feed them,” says Isaacson.

Targeted

Robyn Isaacson doesn’t believe there is a stigma around accessing food through school, something backed up by research.

Julie Chapman from KidsCan: “Research out of Massey University in 2007 and 2010 tells us there’s no stigma attached to food programmes. It doesn’t create a sub-class and that’s one of the reasons it works so well. It provides food when a child needs it, and it’s a very adaptable programme that schools can adjust to suit their particular needs.”

KidsCan is very clear on its objectives: “This is a targeted group and we offer a targeted programme. The aim is not to feed every child attending low-decile schools, just those who need it,” says Chapman.

Isaacson feels that although there is certainly a place for food in schools, it’s right to target the response.

“We have a lot of families at our school who are more than capable and very caring, and if you feed their kids for them you are taking away a responsibility that they are enormously proud of.”

“We will feed any kid who walks through our gates hungry, but that is never all that’s going on,” Isaacson says. “I feel very strongly that if you have kids who are hungry you have to look at what is happening in the family and at home.”

Food skills

“How do we grow healthy kids? First, our kids should be eating regularly – three meals a day and two snacks – but also kids need lots of water and exercise. Those are the basics.”

Lucinda Sherratt is a Hawke’s Bay based clinical nutritionist who works specifically with families and children.

“When a child lacks nutrients they get sick because their body doesn’t have all the good stuff it needs to grow and be healthy.” says Sherratt. “On top of that hungry kids find it difficult to concentrate, and they are often anxious and fidgety.”

Julie Chapman agrees and believes the impact of a lack of food is far reaching: “Hungry children get sick more often, they are more susceptible to cold and flu, to skin and respiratory infections.”

But she also knows hunger can lead to nutrient and vitamin deficiencies, issues with brain development, social issues, bullying and anti-social behaviours, like stealing food, all effects that can impact those people in adulthood.

For Lucinda Sherratt, starting good eating habits early is the key to ensuring children maintain those habits throughout their lives.

“Sometimes it is a money thing but I really think it is also an education thing. How you teach your kids about food in the first place is really important,” says Sherratt, who advocates for education around where food originally comes from. “We have to show our children that food doesn’t just come from supermarkets. I’m a great believer in vegetable gardens.”

The vegetable garden squeezed into the average suburban backyard is not the only option, with two community garden initiatives in particular aiming to feed some of Hawke’s Bay’s most in need families. Te Aranga Marae in Flaxmere and Aunty’s Garden at Waipatu are both excellent examples of a place where families can go to pick their own veges for a small koha.

Lucinda Sherratt believes strongly in teaching the process of garden to kitchen to table. “It gives kids healthy food skills and a sense of pride when they eat things they’ve grown themselves.”

“It is vital we educate all our children about food because it’s as if we have missed a generation of that kind of knowledge – growing food and what that means,” Sherratt says.

Robyn Isaacson is permeating her school culture with the same ethos: “I think part of it is, for some it’s easier to serve up junk than a good meal. People are busy and money is tight. But we have kids in our school who can cook really well and we are teaching our kids more and more food skills. In terms of our technology programme for example, we say ‘Let’s teach technology they can do something with’.”

Local action

Although KidsCan and the government’s Fruit in Schools initiative are both helpful programmes at a national level, a more direct local response is also required.

“One thing I have found is that we’ve got a lot of people calling us wanting to help,” says Isaacson, who admits to being, at first, overwhelmed by the generosity.

“We get people calling with excess fruit, we go to bakeries and get bread to distribute in our community. Recently we had a couple of farmers who have come down from Waikato who want to help us. But what it really needs is someone to coordinate it.”

Isaacson suggests that may be an issue for local government and questions the role of councillors, who she feels could perhaps lend a hand in a very practical way: facilitating and liaising with donors and recipients.

“There are two clear reasons why coordinating donations of food would be beneficial other than the obvious of providing people with a meal: It would give locals an opportunity to contribute to their own community, and none of us likes to see waste,” Isaacson says.

Connecting people can also help create a culture where healthy food is embraced: “I am totally astounded at how great the majority of our families are; however there is a minority of kids who aren’t connected to anybody, no Nan, no family, no one to teach them skills. Wider whãnau is all-important, as long as it’s well functioning whãnau.”

Isaacson feels her school is getting good quality support from initiatives such as KidsCan, but there are still holes. “What we need is someone to help in the family at a family level, because so often to just feed people is not enough.”

KidsCan claims they can feed all 16,000 hungry children in New Zealand with $4 million per annum ($250 per child). When you consider that every year New Zealanders send $100 million overseas to feed hungry children that sum doesn’t seem too great a hill to climb.

Julie Chapman: “I think people are becoming more aware that there is real poverty in New Zealand. I personally feel that yes, we should feed kids, because whichever side of the debate you sit on there are still hungry children. Meeting the immediate need is easy for us to do. Then we can let the government get on with addressing the underlying issues.”

Tiffin & Bento

Even for the most aware parent, filling a lunchbox (or three) every school morning year after year can become a chore soon lacking in inspiration and fresh thinking.

Nutritionist Lucinda Sherratt suggests we should be looking to other cultures to populate and invigorate our lunchboxes.

“There are lots of cultures in New Zealand and they have lots to offer us in terms of flavours and ideas around food,” says Sherratt.

“We have to look outside the sandwich box for inspiration. Fresh healthy food isn’t just sandwiches, it could be dahl and rice, sushi or Vietnamese spring rolls, or tortilla.”

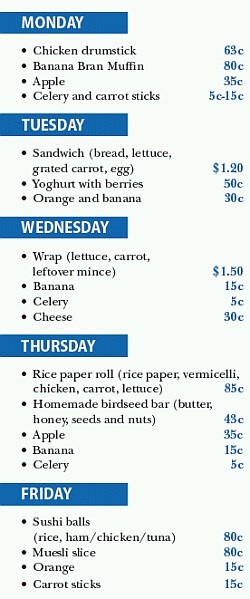

For this story Lucinda prepared a sample weekly lunch menu with a budget of about $2 a day.

Much of this requires home baking and bulk buying, and Sherratt advocates for eating seasonally and buying locally, or better still eating from your own garden. Involving children in the preparation of lunchbox contents can be beneficial, but it’s still vital parents keep control to ensure a balanced diet.

“Incorporating kids into the equation when it comes to what they eat is really helpful. But also, the more choices you give them the harder it is for them to make healthy decisions,” says Sherratt. “If you let them choose between fruit and cake it’s tough for them to make good food choices.”

Another lunchbox dilemma is this:

Do many of us really know what should be in lunch boxes in terms of nutritional content?

When Campbell Live infamously opened lunchboxes in decile 1 and decile 10 classrooms (TV3, August 2012), the nation was appalled to find very little for lunch in the decile 1 school. But in the decile 10 classroom, although the boxes were full and there was plenty of fruit, there was also an abundance of white bread, processed foods and refined sugar, in a myriad of forms.

Ministry of Health guidelines suggest children (aged 2-12) eat the following daily:

- 3 servings of vegetables

- 2 servings of fruit5 servings of breads and cereals, including pasta, rice and noodles

- 2-3 servings of milk and milk products

- One serving a day of protein, such as meat, eggs, nuts, seeds and legumes.

In those terms lunch becomes a big part of the day, believes Lucinda Sherratt.

“If you really care what goes in to the lunchbox it’s going to take time, preparation and thought,” believes Sherratt, but she adds that it doesn’t have to take a great deal of money to ensure kids are eating healthy

lunches every day.