Exactly what constitutes ‘social wellbeing’?

We probably all have different answers. Perhaps the major determinant for each of us individually is our economic comfortability, which might find one of us worrying about finding the next day’s meal, and another obsessing over Flight of the Concord tickets.

To our own personal situations, add our relative social consciousness, which is independent of incomes and status, and ranges from acutely aware and concerned to totally oblivious about the needs of others, especially those struggling to cope.

So for the community the definition is broad – adequate living standards, rewarding work, good health and education, safety, good prospects for our children, robust cultural amenities, enjoyable sport and leisure.

We toil as individuals and as institutions to improve our community’s wellbeing and spread it to all.

How well are we accomplishing that here in Hawke’s Bay?

By many accounts and measures, not well. Certainly not in every dimension. And certainly not for all.

This article, and several of those that follow, focuses on the part of our community that is neediest and having the most difficulty coping. Unfortunately, it’s not a pretty picture.

A sense of scale

In human terms, many o the indicators of social wellbeing in Hawke’s Bay are disturbing. [See chart on next page.]

As a region we have low personal incomes: a median of $22,600, and 5,219 receiving the domestic purposes benefit (DPB). Fully 53% of Mãori in Hastings (51% in Napier) have personal incomes less than $20,000, compared to 45% of all ethnicities in both districts.

We are struggling with employment: 1,834 receiving unemployment benefits, with many more looking for employment. Nearly one-third of our adult population has no formal education qualification. About one-third live in the three most deprived decile areas – with over 11,000 receiving an accommodation supplement, a further index of hardship.

As noted, if one looks at such figures for Mãori (and our much smaller Pacific Islander population), the socio-economic picture is significantly bleaker. For example, 63% of unemployment benefit recipients and 65% of DPB recipients are Mãori.

All of this hardship creates stresses that adversely affect physical and mental health, and even the physical safety of our families: reported family violence offences exceeded 2,600 in Hawke’s Bay in 2009 … and no one suggests that level is decreasing.

Against these ills, government deploys a blizzard of supports and targeted programs, delivered by a small army of bureaucrats and social service workers.

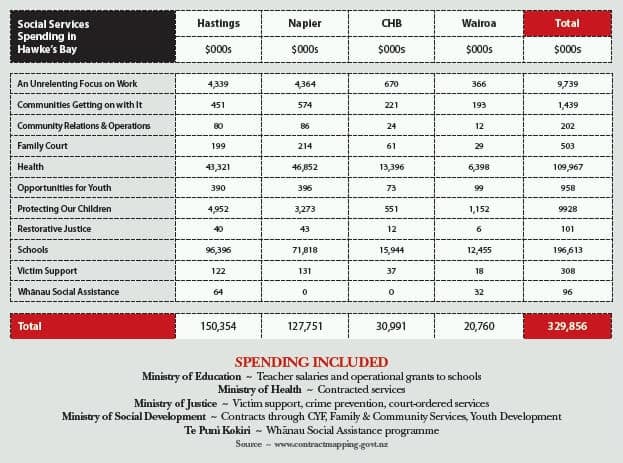

As our Social Services Spending chart indicates, the main service ministries spent about $330 million in Hawke’s Bay in 2011 contracting services on everything from employment assistance and training, to health and education, to family services and protection of children and other victims of violence.

Health and education consume over 90% of that spend, and while all of that contributes to community wellbeing, only a portion is targeted at the neediest in Hawke’s Bay. For example, 42% of Hawke’s Bay students attend schools in the lowest three deciles bracket. And spending specifically targeted at Mãori by the DHB totals about $7.6 million out of a budget of $438 million.

Add to the programme spending the hundreds of millions (a guarded figure at MSD) directly received by our 18,730 recipients (as of March 2012) as some form of ‘main benefit’.

So the scale of social service need, and spending, in Hawke’s Bay is quite significant. And the range of programme support quite diverse.

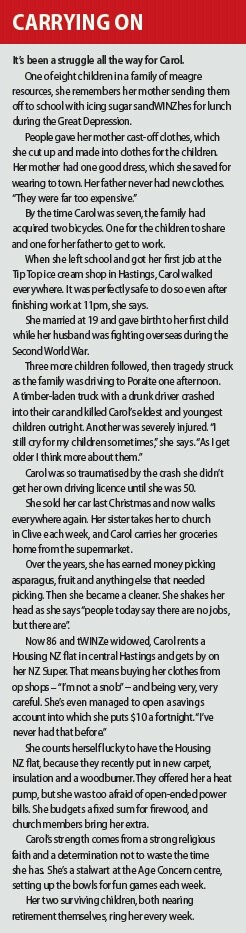

The individuals involved might ‘simply’ be temporarily out of work and struggling a bit; they could be socially isolated, fixed-income elderly with declining health; they could be mothers abandoned with children; or they could be victims of family violence triggered by systemic poverty or drug/alcohol abuse.

To get a more personal sense of who and what the statistics are all about, read through the three

‘profiles’ accompanying this article (names fictitious).

Where does help come from?

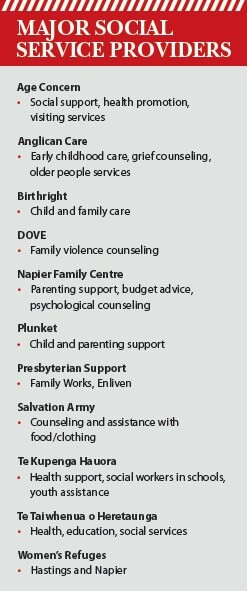

Help is provided by dozens of public and private agencies in Hawke’s Bay.

It’s an exceedingly complex network, as we found preparing our articles. And if it appears complicated and impenetrable to well-educated, calm and reasonably sophisticated, internet-savvy researchers, one wonders what accessing and navigating the ‘system’ must be like for the stressed out ‘client’, who might be barely literate and not even sure of what help they need or what in fact might be available.

Talking to frontline social service providers, the common refrain is that many, perhaps most, clients have multiple issues – drug and alcohol addictions, financial stress, ill health, psychological distress. Their ‘solutions’ might involve housing, medical treatment, counseling of various kinds, financial assistance, job training … through to an emergency food packet or temporary refuge.

Unfortunately, government bureaucracies are silos, not multi-taskers. They have great difficulty dealing with multiple-needs clients. Each agency has its own programmes, contractors, processes, and boxes to tick. Formal structures to coordinate services come and go.

At one point in my research, I was delighted to discover an entity called the Hawke’s Bay Social Sector Group, comprised of 11 government agencies working in the field. According to their web information, the Group, formed in early 2010, “acknowledged that the initial work needed to focus on the activity they do with each other before widening their operational activity to local government, Iwi, and community organisations, recognizing the need to address their own business together first.”

In less than two years, that Group has been disbanded. Apparently the challenge to integrate and cooperate was too great. Or as one insider commented to BayBuzz, too time and resource demanding in the face of personnel and funding reductions that force staff to focus on clearing away increasingly over-full workloads.

So if the problem is, say, youth employment in Hawke’s Bay, any cross-agency collaboration must be built from the ground up, drawing upon those willing to participate. Currently, this problem is to be addressed by the Youth Futures Project, with a group consisting of EIT, Hastings District Council, the Chamber, MSD and Business Hawke’s Bay. Asked why Napier City Council wasn’t involved, the answer given: “It’s a group of the willing.”

Representatives of various government agencies insist that cooperation indeed occurs at a working level, with senior managers estimating they spend a third of their time on coordination efforts, even if more visible over-arching structures are not in place.

For example, Work and Income is proud of its initiative to convert several of its service centres in the region into physical hubs where clients can access multiple service providers, both governmental and not-for-profit organisations. The new centres are called Community Link, and are functioning in Napier, Flaxmere, Wairoa and Taradale, with a new facility opening in Hastings in August. Services might vary by centre, but generally include child, youth and family services (CYF), budget advice, legal help, student loans, health care referral, and youth employment.

However, one observer commented: “WINZ is the worst sponsor of something like that. Clients don’t like going to WINZ. They’re inherently suspicious that their benefits will be challenged.”

Planners versus providers

Compounding the bureaucratic silos, coalface service providers argue that clients don’t get heard by the bureaucracy’s planners.

As one veteran service provider commented: “The priorities and the design of services are developed by people whose masters are, eerily, largely themselves. It is a massive industry – the prioritising and design and funding of social services. People don’t know what works; because often they don’t ask the people to whom they provide the services – and if they do, it is token. … I’ve watched endless models of care, endless acronyms, come and go in the past decade, while the need to listen grows concomitantly.”

This observation is illustrative of many I heard in researching this article. The ‘alliance’ between government agency funders and the actual providers of service is a tenuous one. Most won’t speak about it on the record.

Simply put, providers see planners as aloof from the real world, committed to their own pet theories (seen as unsupported by evidence), narrow gauge instead of holistic, afraid of risk (providers regard risk as inherent, given the clients being served), and penny-wise, pound foolish.

Housing NZ’s recent decision to pull staff from the field and channel clients through toll-free phone intake is cited as a classic bureaucratic blunder, given the complexity of the application process, language barriers, and the technical illiteracy of the affected population. “A system designed to put off clients and reduce the lists,” complained one observer.

Another comment to BayBuzz: the system “spends an awful lot of money trying to ward off any blame. So there becomes a policy for this thing, a policy for that thing … lots of money that could be spent on services to an individual gets spent on protection against doing the wrong thing. This occurs in all areas of social services – it is the story of ‘box ticking’. It is the elephant in the room of social and health services.”

Another senior provider agreed that “there’s never just one problem”. But government programs get more narrow and prescriptive in terms of what services they will fund. Using the example of family violence, she argued that to prevent such violence required teaching a perpetrator “entirely new coping skills … a new way of being in the world,” but also supporting the individual to deal with a “whole raft of issues … housing, financial stress, parenting skills, legal problems.” But this holistic type of support isn’t funded.

Again, with respect to family violence, the Government spends money effectively on a public awareness program (It’s Not OK), but then won’t fund treatment for self-referrals the program generates, which can now be half of those seeking help. Funding is limited to only those referred by the justice system, people who have already committed the offence. Likewise, funding is moved away from community education and prevention to working directly with clients. All examples of trying to fix problems at the bottom of the cliff, as one practitioner observed.

The providers attempt to deal with fragmented government programs by their own networking and informal coordination and referrals. Because the providers actually deal with real-live clients, they believe they are more aware than the funding agencies themselves of the fragmentation. One put it strongly: “We have too many funders not talking to one another. We have health, education, welfare and justice … all need to be linked so that we get a more coordinated approach and an integrated funding and planning framework … We have systemic failure because we are not coordinated.”

But again, the time devoted to such efforts is not publicly funded. Charity fundraising must cover the cost, and those dollars are getting scarcer as well. Moreover, as providers compete for increasingly limited contestable government and charity funds, even their incentives to cooperate are diminished.

Are services keeping pace with demand?

Said one provider: “The need is great right now for those who are most at risk physically, intellectually, emotionally, spiritually – the vulnerable in our midst. That is obvious. What is really scary is we are not only becoming desensitised to abuse, but we are almost becoming bystanders because there appears nothing we can do to stem the tide.”

And another: “We’re not getting results. It’s getting worse and worse. Systemic issues are not being addressed.”

Government agencies are straining; individual providers are straining.

Said one: “Demand is up; our ability to deliver and meet that demand is down.”

A January media release from Napier Family Centre reported: “Our annual results to 30 June last year showed over 1,900 people accessing our services … and in the last six months we have already had over 1,200 people participate in our programmes. This level of demand means we will easily exceed our contracted levels with government agencies.”

Hastings Budget Advisory Service dealt with 521clients last year, and has already seen over 700 this year. HB Today quoted the Service’s Greta Wham regarding a $3,800 top-off grant from MSD: “It will go some way to alleviate servicing the increased number of clients we are seeing.”

A provider familiar with need for services for the disabled estimates that demand exceeds availability of services by 3-4 times.

Statistically or anecdotally, there’s nothing to indicate that economic hardship and its associated stresses are diminishing … or will anytime soon. In its superb report earlier this year, The Growing Divide, the Salvation Army noted that real wages and salaries have not increased nationally in inflation adjusted terms for the past two years. A recent University of Otago study found that approximately two-thirds of people with a low income at any one point-in-time, remain chronically in low income. And as described earlier, household financial duress leads to other problems: domestic violence and adolescent crime, undernourished and unhealthy kids, and poor educational performance.

Then the cycle renews.

From food banks to mental health counselors to employment trainers, no one BayBuzz spoke with expects things to improve any time soon.

What is needed?

The shortest answer, but the longest to deliver, might be more jobs. Jobs for the unemployed. Jobs for the under-employed and for those discouraged from even entering the labour market.

Not just any jobs, but better-paying ones. In December 2011, nationally, the average hourly earnings of the highest paid sector (finance and insurance, at $37.64 per hour) was 2.3 times more than those in the poorest paid sector (accommodation & restaurant, at $16.43). We all realize that Hawke’s Bay has far more baristas than bankers, more seasonal workers than knowledge workers.

And our secondary schools and EIT need to be in synch with the region’s job market … conceptually a no-brainer, but fraught with practical challenges, as Keith Newman explores in his article.

The social scientists and planners say society will be get by far the best return by investing in children – getting them well-parented, healthy and safe in their homes. The Children’s Commissioner, Dr Russell Wills (see his article in this magazine) has pointed out that a child with a poor start in life will cost up to $1 million across the course of their life. Every Child Counts argues that low and ineffective public investment in the early years of childhood (NZ spends just half the OECD average) costs New Zealand dearly – approximately 3% of GDP or $6 billion.

Among other programs, and to the government’s credit, the Social Workers in Schools programme (SWiS) is rated as very promising, identifying and acting upon kids’ diverse support requirements, from shoes and warm clothing to family intervention and health referrals.

Even staid BusinessNZ has chimed in: “There is a growing recognition that the issues affecting children should be the concern of all New Zealanders. Many of these issues are beyond the scope of families alone to tackle, including solo parenting, financial insecurity, difficulties in school, and young people ending up ill-equipped to contribute in the workplace. Families, communities, business and government all have a part to play in addressing these issues.”

Jobs, education and training might be seen as the systemic response. However, while longer term programs gain traction – hopefully in time for Hawke’s Bay’s pending boomlet in kids and youth – there is still plenty of need to help people today to improve their personal and family wellbeing.

That brings us back to the blizzard of social service programs du jour. Here the recommendations from those actually doing the hard yards are consistent.

More funding. All providers would like to see more funding. But as one said: “There is not enough money in the country to resolve the problems we have. Therefore we have to get our thinking caps on and collaborate, partner up and work with others.”

Better coordination. All complain of too many silos, too much turf protection, both by funding agencies and service providers. Opinion is divided as to whether there are too many providers, some without the scale to be effective. “There have been too many in the past. There are probably still too many. Government current thinking seems to be that they will contract with services who are getting results … I think they will be looking for larger and more financially viable services.” Countered by: “The big organisations always think they know best and should be bigger.”

Opinion is also divided as to how to achieve better coordination. Most are fatalistic, believing that as long as separate but overlapping programmes are designed by a handful of ministries acting unilaterally in Wellington, confusion and disorganization at the coalface is inevitable. All further complicated by changing strategies as governments and ideologies change. Many providers are unhappily resigned to needing to devote significant time to fashioning their own networks and informal coordination, at a significant cost against time spent actually delivering services.

Embrace client-centered, holisitic approach. The practitioners all see the need for this, as they are acutely aware that many clients present with a complex of needs that require flexible and comprehensive treatment. But dedicated programs and funding streams thwart a holistic strategy, and coalface providers mostly feel powerless to change thinking originating at the top of ministries. Furthermore, with everyone starved for funds, no one wants to rock the funding boat.

Invest in children and youth. Fortunately, there’s a policy and practitioner consensus here. Most agencies and providers agree that the most bang for the buck would be achieved by focusing on the young, where good patterns can be established, and bad ones more readily broken and mitigated. Interventions must begin at birth (and even before) and run straight through to keeping teens in school, helping them transition to work, and teaching parenting skills to young parents.

How to rock the boat?

In March this year the Government announced a reform programme for councils. Currently the Local Government Act 2002 gives councils a remit to provide for social wellbeing in their communities, but the Better Local Government report says this gives the public false expectations. The report – now translated into proposed legislation – recommends that councils should instead be tasked with “good quality local infrastructure, public services and regulatory functions at the least possible cost to households and business.”

“I welcome central government giving us more clarity around our role, but if they give us clarity and they don’t pick up the need, what will happen to our community?” asks Cynthia Bowers, Hastings deputy mayor. “The public say to us ‘Someone’s got to do it and we want you to.’ Local government is best placed to understand local community needs, but does that mean we have to solve everything, and pay for the solutions? … The dilemma for council is to what extent should we be solving and to what extent should we be drawing a line and saying ‘No, that’s a central government issue.”

Hastings Councillor Wayne Bradshaw sees council’s role as a facilitator: “There’s enough groups and agencies helping out there, we want council to help them collaborate.” He’s a proponent of community-specific plans throughout the area, but adds: “Councils should allocate a budget for each community to spend to achieve their aspirations. That will provide some do and not just talk.”

Mayor Yule observes: “The interaction between central and local government is not ideal and many responsibilities get blurred … The Government is sending signals about reducing local governments’ roles in this space. The obvious and yet unanswered question is: ‘If local government doesn’t or isn’t allowed to provide some assistance in this space, who will?’ No minister has been able to answer this question, other than to say that government departments need to be more accountable. History tells us that councils get lobbied to do things in this space by concerned communities when government agencies have often failed.”

And Mayor Barbara Arnott seems in agreement. She believes in supporting community groups to carry out programmes within the infrastructure provided by local government. “We want our community organisations to be sustainable and resourced. Community development is about funding and facilitation, it’s about putting people together.”

Council, the mayor believes, has a unique position in being able to take an overview of need and resourcing. “We can see where the need is from a big picture view and we can give people a hand where it’s needed.”

For Mayor Arnott, envisaging a community where council has removed itself from all areas except infrastructure is beyond possibility: “I can’t think of anything more appalling,” she says.

So, our elected local leaders appear to believe they have a role to play in securing our community’s social wellbeing … if for no other reason than they feel the heat when things are going wrong.

After all, how many readers of this article would even know that there’s a Regional Commissioner for MSD here in Napier, or what he does and doesn’t have authority over? How many could identify the top official in our region for Child, Youth and Family Services? Or the regional head of Housing NZ? [Actually, there isn’t one.]

This bureaucratic anonymity – our inability to pinpoint responsibility – is a guaranteed recipe for unaccountability for meeting the social wellbeing aspirations of Hawke’s Bay.

If our mayors were to get on the plane to Wellington, and take on – as a high priority – the mission of convincing Government that their system is broken, an army of social service providers in Hawke’s Bay would jump to their feet and cheer.

It’s time to rock the boat.