What is an EOC?

Many of these contaminants are not new or ‘emerging’ at all. Indeed they have been part of our everyday lives for decades. New compounds are created through the fusion of chemicals or changes in the use or disposal of existing chemicals.

Carefully disguised in personal care and ‘life-style’ products, domestic cleaning products, pharmaceuticals, veterinary medicines, industrial compounds and by-products, pesticides, herbicides, steroid hormones excreted by humans and animals, and food additives (to name a few), these contaminants have simply avoided the limelight. The extensive range of ‘everyday’ or High Production Volume (HPV) chemicals that enter our environment is uncontrollable, unregulated, and unmonitored … and they steadily accumulate.

The US Geological Survey has defined an EOC as “any synthetic or naturally occurring chemical or any microorganism that is not commonly monitored in the environment but has the potential to enter the environment and cause known or suspected adverse ecological and (or) human health effects.”

Found in nanogram to microgram per litre concentrations, EOCs have been historically difficult and expensive to identify. However, through a combination of growing concern, and advances in analytical testing technology, scientists are now able to detect EOCs with increasing accuracy.

International and New Zealand-based studies, although primarily focused on wastewater streams, biosolids and sludge, have revealed the frequent occurrence of EOCs throughout our environment. They have been detected in soils, air, surface water, groundwater, storm water, sediments, fish, marine environments, and humans.

Recent studies in America found traces of eighteen unregulated chemicals, which included perfluorinated compounds (PFCs), herbicides, solvents, caffeine, antibacterial compounds and a commonly prescribed anti-depressant fluoxetine (Prozac), in more than one-third of US drinking water utilities.

These findings led the US Environmental Protection Agency to place four of the identified contaminants on the list for consideration for future drinking water standards. These priority contaminants are perfluorinated compounds, PFOS and PFOA (Scotchgard and Teflon), the metal Strontium (extensively versatile – pyrotechnics, treatment of osteoporosis, an ingredient in sensitive teeth toothpaste, used to process sugar, CRT monitors, colour television sets), and the herbicide Metolachlor. All these contaminants are known to cause adverse human health effects ranging from cancer to thyroid disease.

Closer to home

Research into EOCs has been slow and relatively unsupported in New Zealand, but the concern is valid and growing. Sally Gaw, Senior Lecturer in Environmental Chemistry at the University of Canterbury explains: “EOCs are a burgeoning and extremely diverse class of naturally occurring and synthetic contaminants that are not routinely monitored. Many of these would have been present in the environment for a long time. They have the potential to have adverse ecological and human health effects.”

In addition, EOC contamination of our water could jeopardise markets that are dependent on our water’s ‘purity’ – both as a ‘pure’ product for direct sale and as a key ingredient in value-added foods from infant formula to juices.

We are all long-term consumers of chemicals. We may not have the same ‘problem’ chemicals as in the US, but we will have our own unique set. This concern was addressed by Graham Sevicke-Jones (former Science Manager for Hawke’s Bay Regional Council) in 2011 when he was granted approval from council to commission a report from Cawthron that focused on the risks and impacts EOCs potentially could have in Hawke’s Bay.

Sevicke-Jones, who now has the same role at Greater Wellington Regional Council, says: “There are huge knowledge gaps in New Zealand regarding EOCs. There is no strategy, and no national direction, there is no government determination to do something; EOCs are simply not there!”

“The report was commissioned as a document that could be used again, a useful perspective, and an opportunity to review the current available data in New Zealand. It enabled us to get a feel, an insight, as to where New Zealand ‘stood’ in regards with EOCs.”

The report reinforced the concerns held by Sevicke-Jones. It reiterated the knowledge gaps regarding occurrence, concentrations, persistence, environmental fate, and the potential risks EOCs could have on human health, New Zealand’s unique ecosystems, and Hawke’s Bay’s local economy.

It emphasised that Hawke’s Bay is really no different from any other part of the developed world. The concentrations of the limited number of EOCs measured in New Zealand are similar to those from overseas studies, and that it is likely the concentrations of those that have not been measured are similar to those reported overseas. The report indicated that the impacts and pressures observed in other developed countries will be comparable in Hawke’s Bay.

Similar studies conducted by NIWA focused on receiving environments around Auckland have made the same observations.

Passionate about being ‘proactive’ rather than ‘reactive’, Sevicke-Jones believes: “We urgently need a nationally organised group with an advisory capacity for future policy. We need to get better connected internationally, which will enable us to stay up-to-date with new research. With a coordinated, bottom-up approach we can share costs, as research in this area is expensive. New Zealand has got some great brains in this space! Enthusiastic and highly knowledgeable!”

HBRC Resource Manager Iain Maxwell agrees that EOCs can be seen as an additional environmental stressor. However, he feels that regionally there is not a great deal we can do about it: “At the moment we simply do not have the knowledge or the financial resource to look at it properly – we have to prioritise, and EOCs are currently ranked lower than other environmental concerns such as sedimentation”.

Maxwell takes a somewhat philosophical view: “Emerging organic contaminants are a ‘wicked’ problem, a problem in which the solution does not fit in with our current conventional modes of thinking; it is a complex issue, and problems so complex need an entire society to solve.”

A ‘flush and go’ society

Jason Strong, an environmental consultant based in Napier, is currently working on a PhD focusing on EOCs found in wastewater treatment plants. “It is the most comprehensive sampling analysis in New Zealand of wastewater. I am analysing the wastewater for over a hundred different chemical compounds, including fragrances, detergents, parabens, triclosan, insect repellent (DEET), flame retardants, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH’s) to name a few. Unfortunately, this is only tip of the iceberg stuff”.

Strong explains that the number of chemicals synthesised and marketed yearly is increasing exponentially. “There is little or no information regarding the potential hazards and environmental fate associated with a large number of these chemicals. Many of these are in everyday use. Worryingly, it is not just the parent compound we need to understand, it is the breakdown products. These can be more toxic than the original compound!”

“We are a ‘flush and go’ society, says Strong. “All waste ends up somewhere, just look at history – chemicals are not a new problem, take DDT and PCBs for example. Despite these chemicals being banned, they continue to show up in the environment years later. The problem is, chemicals are added to the environment in such small concentrations, and it is only recently that technology has been able to measure these things. However, if you keep adding a little at a time, eventually it becomes a heap”.

This ‘showing up years later’ is characteristic of EOCs. A number of these compounds can stay persistent in the environment decades after they have been flushed away. They can bioaccumulate in aquatic organisms, and sediments can act as a sink in which EOCs can later be released. The nature and degree of natural attenuation of EOCs is poorly understood and difficult to predict. Though many EOCs do break down naturally through photodegradation and biodegradation, it is the ongoing discharges that can result in environmental damage.

The Cawthron report indicates that our region is comparable to other provinces in New Zealand, and that New Zealand is comparable to the rest of the developed world, so where are these EOCs ending up, and could they eventually show up in our water supply?

Getting into the water

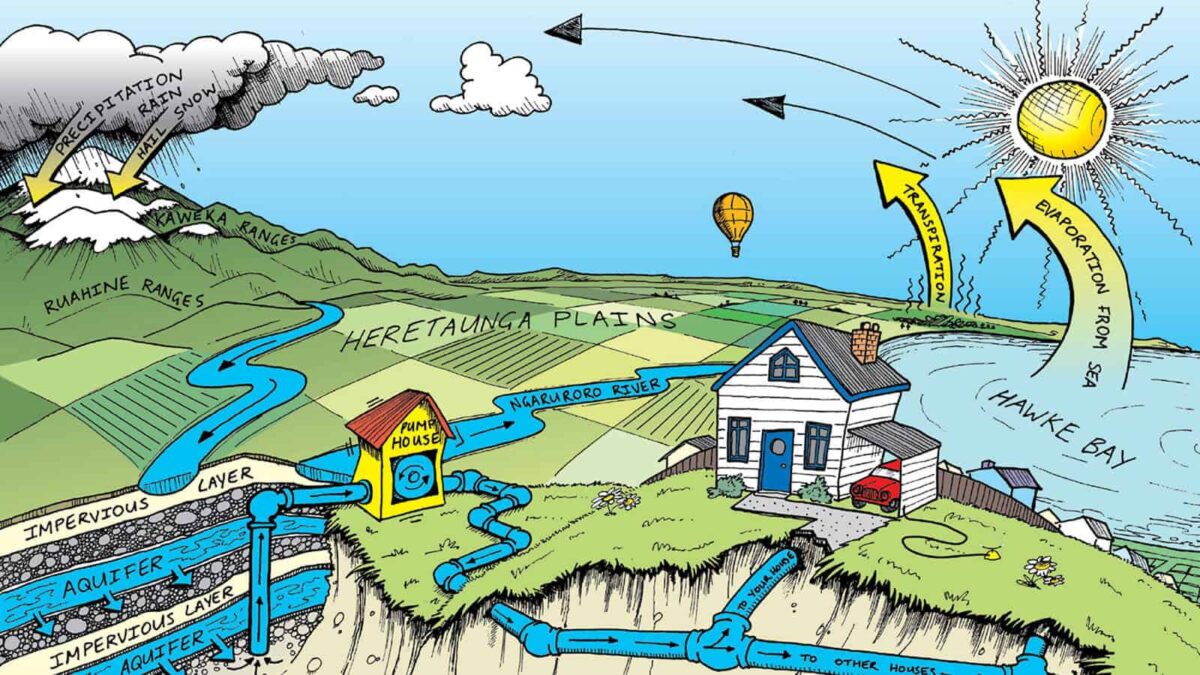

The major sources of EOCs into the environment come from wastewater discharges, stormwater discharges, landfill leachate, incineration, agricultural wastes, run-off from the land, manure application to the soil, horticultural activities, solid waste disposal, old leaky septic tanks, and atmospheric deposition. Indirectly EOC’s can find their way into groundwater through the interaction of surface water with groundwater, aquifer re-charge zones, soakage pit drainage, and other land-use activities over unconfined aquifer systems.

The Heretaunga Plains unconfined and confined aquifer system is the main groundwater resource for people living on and adjacent to the plains. Primarily the aquifer is recharged by the Ngaruroro River. However, evidence shows that some Havelock North wells are recharged by the Tukituki River. The Tukituki River receives ‘treated’ sewage from the four wastewater treatment plants in Central Hawke’s Bay.

Hastings District Council and Napier City Council both reinforce that our cities’ water supply is ‘secure’. Secure means that no treatment is required. Areas that do require treatment (not secure) include Esk/Whirinaki, Waimarama, Waipatiki and Omahu Township.

Dylan Stuijt, HDC water manager: “The council manages the HDC’s various water supplies in accordance with the New Zealand Drinking Water Standards 2005 (2008 Edition). The DWS sampling requirements are listed in the standards and are very prescriptive. The source and reticulation have extensive routine sampling requirements. Areas of sampling include Bacteriological, Protozoa, Viruses, Cytotoxic, Chemical and Radiological.”

Stuijt emphasises that only in exceptional circumstances is water treatment needed, as most of our water comes from a depth of over 50 metres. Recently Havelock North experienced one of these ‘exceptional circumstances’ when the supply became contaminated by E.coli and a bore was shut down. It is confirmed that the aquifer in that area can become contaminated by old primary septic tank in-ground trenches which discharge over and into the Heretaunga Plains aquifer. The high rain fall experienced recently may have exacerbated this.

This is the not the first time residents of Havelock North have had their drinking water supply contaminated. In the year 2011-2012 the annual drinking water survey confirmed that Havelock North had one of the highest number of E.coli transgressions in New Zealand, swiftly dealt with through chlorination. But chlorination (and many other forms of treatment) are ineffective in removing EOCs, which, combined with chlorine, can produce undesirable by-products.

‘Pure’ enough for export?

Water is understandably a hot topic in our region, and the focus on the Heretaunga aquifer has been largely on quantity – allocation issues. However, quality is equally as important, especially if your branding depends on this. For both Trevor Tailor (managing director, Elwood Road Holdings) and Paul O’Brien (general manager, One Pure) ‘purity’ is the essence of their bottled water brands destined for the Chinese market – ‘New Zealand Miracle Water’ and ‘One Pure’.

Taylor says: “It is essential that the land is not contaminated to ensure our underground water does not get contaminated. In regards to EOCs I feel it is a central or local government ‘fix’; I am no scientist but our water is considered ‘pure’.”

O’Brien at One Pure says: “We routinely test our water for 33 different things, this is above and beyond the necessary requirements for the export of bottled water; in reality, there are very few regulations surrounding this. Medium to large outfits are encouraged to belong to a food and beverage trade association, but there are many cowboys out there. We are not testing for EOCs, but if this became an area of consumer interest we would certainly consider it”.

O’Brien notes that existing tests taken from a bore in Awatoto that extends 50-60 meters down reveal some interesting results. “The water from this bore is over 42 years old and seems to come in batches; results remain consistent for a duration of time, then they change, but remain the same for another duration of time. It is like the aquifer is living and breathing.” O’Brien strongly feels we need to take a precautionary approach: “If the aquifer is struggling, let’s find out!”

Clearly, EOCs are a ‘cross agency’ concern – the environmental implications overlap with human health. Dr Nicolas Jones, Hawke’s Bay District Health Board medical officer, says EOCs have been on the radar for a considerable time. “In New Zealand we rely on the results of overseas research. It is hard to legislate to control the levels of EOCs until we have the relevant data; currently it is very difficult to take any action.”

He sees that Hawke’s Bay’s agricultural, horticultural and industrial activities, some of which take place directly over the aquifer, could be contributing EOCs into our environment, but with a small population, “on an international scale [these amounts] could be considered tiny. Our cities’ wastewater plants discharge directly into the ocean, where many chemicals will be diluted to a safe concentration rapidly.”

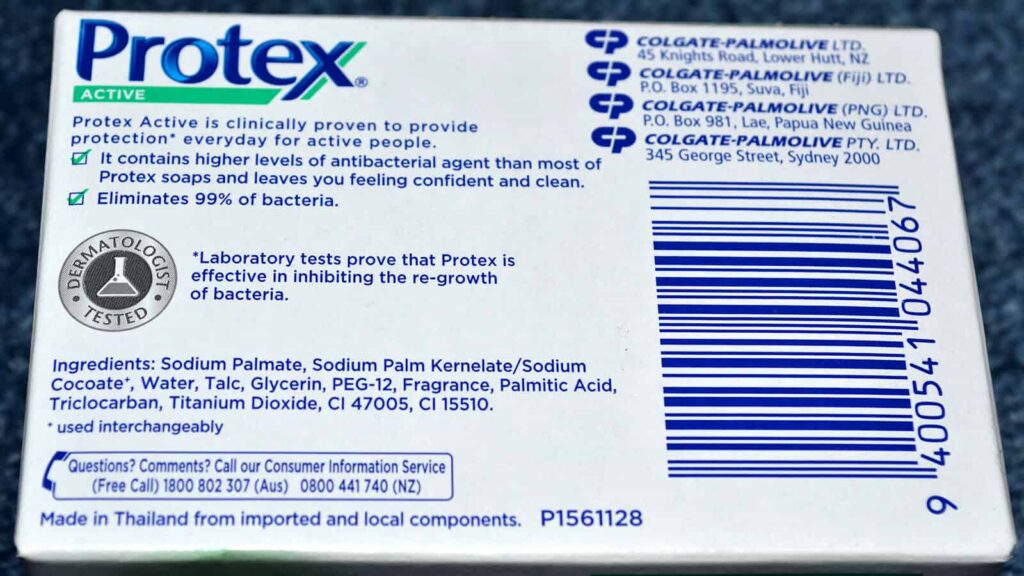

Jones has major concerns around endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) and personal-care products that contain antibacterial agents: “It is well documented that low-dose EDCs can have adverse impacts on both human health and aquatic organisms. They are widespread and found in many goods, including antibiotics, hormones, steroids, disinfectants, sunscreens, fragrances and insect repellents”.

Antibacterial agents, such as Triclosan (still found in many products), have been shown to impact soil microbial activity which effects soil biomass and function. Products containing theses agents are considered a factor in the emerging human resistance to antibiotics and Jones says they’re mostly unnecessary. “It’s advisable to wash your hands with something antibacterial when you are caring for someone who is being sick or has diarrhoea, but on a day-to-day basis I simply use a natural soap and water”.

Jones believes: “It is unrealistic to think we could stop using chemicals over night, but we do have some tools to hand. These include us, the community, and taking responsibility for what we flush down the drain, put into our wastewater systems, and septic tanks.” These solutions are known as ‘Up the Pipe’ Solutions [see sidebar].

With unlimited use and diversity, EOCs will pose a real threat to our region’s fresh water bodies and aquatic ecosystems that cannot be ignored. NIWA gets the last word: “The effects of EOCs on people and our unique environment and ecosystems are still barely understood. There is a clear need for a national strategy to manage the risk of EOCs to the New Zealand environment.”

Up the Pipe Solutions

While EOCs will probably be addressed by drinking water standards, environmental quality criteria, and groundwater threshold values in the future, it is better to be proactive and practise as many of the ‘Up the Pipe’ solutions in the interim as we can.

- Think before you pour something down the sink or toilet

- Return all unused prescription medicines back to the pharmacy

- Correctly dispose of hazardous household products

- Reduce or eliminate personal care products that contain antibacterial compounds

- Maintain home septic systems properly

- Do not over water your garden

- Try to limit the use of chemical fertilisers, pesticides and herbicides

- Decrease impervious surfaces around the grounds of your home

- Plant native species that thrive in the region’s natural climate and soil type

- Recycle and dispose of all your rubbish properly

- Compost kitchen waste

- Maintain your car well (avoid oil and fluid leakage)

- Be ‘green’ when washing your car

- Think before you make a purchase – is this really necessary? Is there a natural alternative?

This is of major concern as most of these chemicals are residual and could merge with, yet to be brewed, wonder products . The diagram, preceding this article, is one we should all recognise, as it was a regular lesson in Hawkes Bay classrooms for years.

The biggest concern we in the bay face, is the continued issuing of oil prospecting licenses and the spectre of TPPA. This Corporate instigated, so called, trade agreement would allow the worlds worst polluters free range to “frack” and pump their caustic mixes into our aquifers, with no concern for the environment. All for the minimal 4% of profits that has been negotiated.

We, could not, can not, control, or restrict, these Multinationals in their pursuit of the elusive “fossil fuels”. Of which there are enough known reserves world-wide to drown us all now, according to the Climate change theorists.

An excellent article, Sarah. These compounds will, sooner or later, be tested for in our primary industry products, with very bad consequences for our international exports. Overseas consumers are becoming increasingly conscious of pollutants and it is in our national interest to get ahead of the game, not wait until something serious happens. Our “clean and green” image is already somewhat shaky.