Where and how better to be amused than by attending meetings of our local councils, which were long accustomed to operating without any meaningful outside scrutiny.

At scores and scores of meetings, I was the only outsider in attendance. The dictum – ‘The smaller the issue, the bigger the debate’ – was proven over and over, providing ample grist for writing.

However, amidst the squabbles over speed hump placements and beautification plantings, serious issues were indeed brewing … and these became the staple of BayBuzz reporting.

The very first printed edition of BayBuzz in September 2008 included articles on these subjects: sewage in the Tukituki, plans to massively develop Ocean Beach, the proposed Regional Sports Park, and complaints of pollutants from the Whakatu industrial area in the Karamū Stream.

Without delving into all the pros and cons, here’s just a taste of the battles fought.

Tukituki water quality

Living along the Tukituki, just after moving here I took fly fishing lessons. I expected to eat my trout, but was warned off that by locals who educated me about the poo ponds down in CHB.

I joined the ‘downstreamers’ who wanted the Tuki cleaned up – and promptly – as required by an Environment Court edict won by two activist appellants, Bill Dodds and David Renouf. These two successfully challenged the limp wrists of both the Regional Council and the CHB District Council, setting in motion a tougher sewage clean-up regime that after ten years is still not completely satisfied.

More broadly, the Regional Council found itself under close scrutiny for its handling of the Tukituki for the first time. Outside consultants hired to ‘test’ the contentions of Dodds and Renouf concluded that the activists were indeed in the main correct. Pressure continued.

Finally, Plan Change 6 dealing with Tukituki clean-up and water allocation was formally in place by 2015, and nearly 1,000 farmers have prepared Farm Environment Management Plans that, when implemented, are supposed to yield better water quality. The verdict remains out on that.

Ocean Beach

About the same time, the ambitious plans of Andy Lowe to develop Ocean Beach, endorsed by the Hastings Council, came into full view. His plans for 1,000 houses at Ocean Beach generated close to 11,000 petitions against. Folks like Chris Ryan and Anna Archibald led the campaign, which began in January 2008.

By the end of 2008 the Council was budgeoned into submission and recanted its support. Lowe withdrew his plan.

BayBuzz wrote at the time regarding the withdrawal letter sent by Lowe’s then-general manger, Phil Hocquard: “In his letter, Mr Hocquard notes:

“There is no doubt that development at Ocean Beach will continue to occur …” Later he concludes: “For the moment, this particular plan change process is at an end.” That — and the ‘legal brief’ nature of the withdrawal letter — suggests we haven’t seen the last of Andy Lowe and Hill Country at Ocean Beach.”

Indeed, years later Andy Lowe has returned with a new scheme for ‘eco-development’ at Ocean Beach. The Hastings Council viewed this scheme favourably, including it in its own proposed District Plan. Lowe opposed conditions that would limit the extent of development and the matter went into Environment Court mediation. With HDC largely mute, objectors Future Ocean Beach Trust won some constraints on the scale of development.

Again, citizens mounting the defence. At this point, it is unclear what development will occur.

Regional Sports Park

In April 2008 the Hastings Council opened public consultation on its proposed Regional Sports Park.

Opponents objected to costs and revenue projections, and cited inaccessibility of the site, fears that the Sports Park would suck spending from neighbourhood sport fields and facilities, misuse of prime horticultural land for this purpose, and over-selling of claimed health and social benefits. And some preferred to refurbish Nelson Park.

BayBuzz wrote: “The case for the financial viability and economic benefit of the sports park rests on a host of ‘build it and they will come’ projections regarding participant usage, event hosting and visitor expenditures.”

Proponents carried the day, when a surprise overnight ‘conversion’ by one Hastings councillor swung the vote in favour of proceeding.

As it turns out, the Sports Park has proven its value in several key respects – excellent usage growth by our local sport community, ability to attract national and international competitions, and successful leveraging of external funding (at least to meet capital needs). And very importantly, Graeme Avery arrived to champion a true health/fitness and sports excellence capability at the park, but with tentacles reaching into the community, especially targeting our youth.

Sacking the DHB

In late 2007, then-Health Minister David Cunliffe (Labour) sacked the Hawke’s Bay District Health Board, just weeks after their election, and appointed a team of commissioners, led by a new chairman, Sir John Anderson.

All hell broke loose, with the region’s elected officials uniting in support of chairman Kevin Atkinson and the rest of the ‘sacked seven’ elected board members. Our five councils mounted a challenge in the High Court. The issue simmered for months. BayBuzz wrote extensively on the issues, drawing upon the Court evidence to support restoration of the elected board.

A new National Government was elected in late 2008, and by February the new health minister, Tony Ryall, had reinstated the elected members alongside the three commissioners. And importantly, the DHB CEO who triggered the groundless controversy resigned.

The odd arrangement worked amically enough and the story ended happily, with an elected board – no commissioners – resuming responsibility after the October 2010 elections.

And finding itself amidst a new controversy.

Cranford Hospice

Throughout 2010 the iconic Cranford Hospice was in siege mode.

The clinical staff had revolted against the management team installed by then-owner of the hospice, Presbyterian Support East Coast (PSEC).

Former and present clinical staff alleged that quality of care was suffering in an environment of insensitivity and misplaced responsibility at best – and bullying and intimidation at worst.

Their concerns first arose in 2008 and were championed by Dr Libby Smales, who had served as Cranford Hospice medical director from 1985-2000, and her successor, Dr Kerryn Lum.

BayBuzz broke the story of deep dissension in February 2010. Dying in Hawke’s Bay is one of the most in-depth series BayBuzz has published. Writer/reporter Mark Sweet and I spent at least sixty hours pulling it together, interviewing seventeen knowledgeable insiders in depth, some repeatedly, and an equal number informally. We reviewed a range of documents, public and privileged.

BayBuzz received a fair amount of criticism at first given the reverential status Cranford held with most of the community. But our facts held up.

As coverage continued, by mid-2010 PSEC’s management role vis-a-vis Cranford had been severely criticised by those most informed, as well as by independent auditors. PSEC’s former chair and CEO both resigned to pursue other opportunities.

At the same time, however, the DHB, who provides the bulk of Cranford’s funding, oversaw a ‘house-cleaning’ of Cranford medical and nursing staff. The handling of this was not a high point in DHB integrity. One official involved termed BayBuzz a “vehicle for menopausal shit-stirrers”.

Confirming the seriousness of what was going on, in-patient care at Cranford Hospice was suspended.

The situation was resolved at a governance level when Mayor Yule brokered an arrangement where PSEC withdrew from its role and a new independent trust was established, with strong community leadership, to own and manage Cranford. A new Board was named in July 2010.

Eventually, on 15 March 2011, the mistreated nurses were vindicated in an apology advert published in HB Today by PSEC.

Amalgamation

As contentious as these issues were, they barely held a candle to the two most politically divisive issues of the past decade – amalgamation and the Ruataniwha dam. These two issues probably consumed more pages of BayBuzz than all other issues combined, including editions totally devoted to the proposals.

The amalgamation debate stretched over six years, starting in August 2009 when Mayor Lawrence Yule – immortalised as the Hero of Heretuscany by BayBuzz pundit Brendan Webb – announced he would stand for re-election in 2010 with amalgamation as the central plank of his campaign.

A Better Hawke’s Bay, a citizens group chaired by Rebecca Turner, was launched in 2011. It championed amalgamation and submitted a reorganisation proposal to the Local Government Commission, the body that subsequently put a specific plan – combining all of the region’s five councils – to the public for a vote.

BayBuzz strongly endorsed amalgamation. No space here to rehash the pros and cons. Would amalgamation save money or not? What efficiencies would it generate (or not)? Would it stifle localism or enhance accountability? Were there alternative ways to achieve the objectives? Suffice it to say the campaign became quite intense and personal at times.

After a huge 62% turnout, the deciding referendum results – 66% opposed region-wide (88% opposed in Napier) – were announced on 15 September 2015.

Despite an embarrassing loss, Yule was re-elected mayor a year later, while chief antagonist Bill Dalton was crowned without opposition. BayBuzz ate crow, but continues to see wisdom in its position, as our councils continue to spend wasteful energy and ratepayer resources in outright warfare and behind-the-scenes competition, blurring accountability at every turn, creating yet another ‘Joint Committee’ each time a serious issue arises. But I digress.

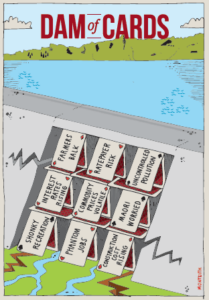

The Dam

Over the same period, passions were equally enflamed over the proposed $330 million Ruataniwha dam. The proposal germinated quietly within HBRC in 2009, leading to a formal feasibility study accepted by the Regional Council in October 2012. Beginning in early 2010, a two-year stakeholder process was also conducted, but its outcomes were ultimately rejected by its environmental participants (including me) in 2012.

The dam issue became far more visible when a government-appointed Board of Inquiry (a process designed to avoid Environment Court scrutiny) heard 27 days of evidence and submissions in late 2013 and early 2014. The Board’s initial endorsement of the dam in June 2014 merely began the full-scale political and legal battle over the proposal.

By then, four councillors – Rex Graham, Rick Barker, Peter Beaven and myself – who had campaigned as critics of the proposal, had been elected as a minority of four on the Regional Council.

Once inside the tent and able to fight for information, the deficiencies of the case for the dam became ever more apparent. But it took another election in 2016 to deliver an HBRC majority opposed to the project. Finally in July 2017, following a series of legal setbacks for dam proponents, the final backbreaker came when the Supreme Court disallowed the DoC land swap needed for the dam reservoir.

Politics of purity

Attaining purity in any situation is challenging. In our local politics, the debates around purity have focused on drinking water – overall safety, chlorination and flouride, the threat of fracking – and GMOs.

Of course, the real issue is impurity. The gastro outbreak in Havelock North in August 2016 set in train, first, a shower of cross-accusations as the Hastings Council, the Regional Council and the DHB each sought to minimise their culpability.

BayBuzz devoted most of its Nov/Dec 2016 edition to examining the issues.

A Board of Inquiry apportioned blame across the three, with HDC bearing the brunt of its criticism. No heads rolled over the calamity, which apart from its severe health impacts imposed a $21 million cost on our economy. The public had its chance in the 2016 elections, but, apparently in a forgiving mood concluded simply that ‘s**t happens’.

Indeed, political intensity over what to do next seemed to overtake the demand for political accountability regarding those officials responsible for the gastro outbreak in the first place. The issue: to chlorinate … or not.

At a recent meeting of the Hawke’s Bay Drinking Water Governance Joint Committee (known by insiders as the HBDWGJC), we received an enthralling presentation on animal feces and the microscopic bugs and viruses who call that home.

The public health expert had calculated that to infect the individuals who had suffered from the 2016 Havelock North gastro outbreak, 50 campylobacter bacteria would need to have been ingested per person. Surprisingly, the amount required to infect all 6,500 people could be found in just 11 teaspoons of sheep feces … a teacup’s worth.

He introduced us to the other bugs and viruses that travel through water to cause human health problems, noted that New Zealand has a poor track record on such incidents, and showed the connection between our huge cattlebeast and sheep population, their even huger volume of excrement (the equivalent of 464,400,000 humans) and the resultant threat to our drinking water … be it drawn from waterways or aquifers.

While he didn’t explicitly advocate for particular mitigating measures, he left no doubt that, in a beef/lamb/dairying economy, controlling land-use practices alone could not provide the drinking water safety modern society expects.

Chlorination anyone? UV treatment? It turns out that some microscopic water-borne threats to our gut can be killed by chlorination; but others must have their breeding blocked by UV radiation … and vice versa.

I suspect that any public official receiving that briefing (the video is online on the HBRC website, search: Agendas) would find it extremely difficult to oppose water treatment.

That said, those who are opposed to being forced to ingest chemicals with their water are numerous and passionate. So the political battle lines are drawn, with a sizable constituency deeply resistant to chlorine treatment.

Before chlorine came flouride. A campaign to remove flouride from the Hastings water supply came to a head in 2013, when 64% of voters in a Hastings District referendum supported keeping flouride in, making Hastings the only district in the Hawke’s Bay area with a fluoridated water supply.

Another perceived threat to Hawke’s Bay water surfaced in 2011 when potential oil and gas exploration in the region raised the spectre of fracking that might contaminate the Heretaunga aquifer or its freshwater catchment with toxic chemicals. Initial feasibility studies projected that as much as $100 million might be spent by oil companies on exploration across the East Coast Basin, and significant production could inject up to $255 billion into the region’s economy over 50 years.

But in 2012 the Parliementary Commissioner for the Environment issued a cautionary report on the risks of oil and gas development in New Zealand, in which the Hawke’s Bay region was singled out as particularly risky because of its geologic instability.

By then, the environmental community – led by Don’t Frack the Bay and Guardians of the Aquifer – had risen up strongly in opposition, supported by growers and others concerned about the integrity of their water supply.

In response, the Regional Council in 2016 triggered investigation of a potential Plan Change that would bar any oil and gas development that might endanger water supplies, putting HBRC on a collision course with then-Energy Minister Judith Collins. That initiative has been placed on simmer, as the new Government’s decision to bar new development, coupled with oil company abandonment of East Coast permits, have lessened the urgency for local action.

While protecting our drinking water was getting all this attention, another campaign was underway, initiated by Pure Hawke’s Bay in 2011, to keep the region GM-free. Armed with a Colmar Brunton poll finding that 84% of respondents favoured GM-free status for HB, and backed by a ‘Who’s Who’ of HB’s growers and farmers, by 2015 Pure Hawke’s Bay had convinced the Hastings Council to, in its District Plan, block genetically modified food production.

This led to protracted legal battle with Federated Farmers, which finally ended this August when the Environment Court found in favour of HDC and Pure HB, confirming HDC’s right to regulate in this area.

Baubles

When it comes to ratepayer funding of amenities, one resident’s passionate, urgent ‘must have’ for the district or region is another resident’s needless, wasteful bauble. Over the past ten years we’ve seen this play out over and over. Whether we’re talking sports park, velodromes, Opera House, swimming (or canoe polo) pools, sports and health centre, aquarium, museum, the pattern is clear …

There’s a gleam in the eye of a passionate vanguard … they win the attention of a council champion (mayor, chief executive) … a feasibility study is commissioned … it projects fantastic utilisation, revenue and external funding prospects (i.e., miracle leveraging) … a battle for the hearts and minds of average punters begins, perhaps around a desultory consultation process.

As the project simmers and gets examined more closely, costs tend to escalate, revenue seems to decline, erstwhile funding partners come and go. Always, there are passionate advocates and equally passionate opponents. Other than perhaps older fixed-income residents being more fiscally cautious, there is no set political fault line on such spending, the line gets re-drawn project by project. Such is politics.

The numbers confronting ratepayers are formidable (even accounting for risky external funding): regional sports park ($50m+), sports and health centre ($15m), velodromes ($21m Hastings, $22.9m Napier), Opera House strengthening ($11m), canoe polo pool ($1m), Napier aquatic centre ($41m), Aquarium expansion ($53m). Total of this list is $215m.

As noted, ‘external’ funding (Government, trusts, sponsorships) is always projected ambitiously for such projects. And some champions, such as John Buck and Graeme Avery – are more successful fundraisers than others.

In recent years, some projects have made it through this gauntlet – Opera House refurbishment, MTG, Regional Sports Park and the fitness centre; some fail – two velodromes; some twist in the wind as debate continues – Napier’s aquatic complex and Aquarium enhancement. Such battles will never end.

To some in the community, the cosmetic appeal of such projects means they consume too much resource (councils’ time, energy, money and political effort) to the neglect of more urgent and overdue infrastructure (water supply, storm and waste water systems) improvements. This would seem to be validated by the very substantial infrastructure spending all councils in the region included in their most recent Long Term Plans – reflecting a political shift that is perhaps the one good outcome of the gastro outbreak and lesser Napier scares.

Emotion

Some of our region’s political battles do not carry the life-and-death or macro-economic significance of drinking water safety failures or $330m dams.

Yet they nevertheless stir passions in the community because they touch deep nerves or challenge fundamental principles and values that some hold sacred. The battles around these kinds of issues can become highly symbolic and sow the most discord and energise more people … sometimes with facts as a casualty.

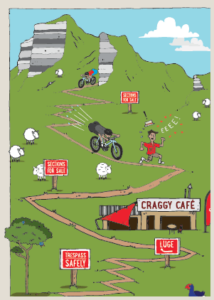

One might look at Napier’s Convention Centre/War Memorial dispute and Craggy Range Track as examples.

More than any actual physical outcome, Napier’s Convention Centre/War Memorial debacle is about disrespect, breaking of a commitment, dishonouring the past. Bureaucrats are particularly clumsy and tone deaf when it comes to recognising the importance of emotion in decision-making. Partly, that’s why we have politicians. Politicians are supposed to at least know better, if not feel genuine empathy. Of course they have to be listening.

And then, the Craggy Range Track. To thousands, a welcome amenity from a generous donor, for which we should be terribly grateful, even if the process doesn’t stack up. To other thousands, a desecration of taonga and a scar on an iconic landscape, inflicted without due process, for which we should be ashamed.

If the track were to be kept (now challenged in Court), there would not likely be a loss of life or 6,500 people seriously ill. If the track were removed, the regional economy would not collapse (nor would Craggy Range).

The intensity around this dispute is not about grave dangers, it again is about violation of deeply held values and principles – property rights, aesthetics, duplicity, the right to be heard, and Māori tikanga and taonga. In some cases, further fueled by blatant racial prejudice.

Issues like the War Memorial and Craggy Track stir deep antagonisms that carry on. They are unlike fights about velodromes or pools, which, while tempers might rise, simply stir spirited arguments, then end.

Coming soon

No doubt I’ve left out some important political squabble of the past decade. Delving into electoral politics – local MPs, mayors, councillors – would require another entire article. In a nutshell, Barbara Arnott abdicated at her peak, Lawrence Yule dodged bullets and optimised being likeable, the Regional Council make-up transformed, and CHB elected in Alex Walker the mayor it needed.

Some of the political issues noted above are unresolved and will carry into the future … notably anything to do with water. For example, the TANK outcome determining the water future of the Heretaunga Plains.

And the future will bring new political challenges as well. The three most consequential in my judgment will be coming to terms with Māori aspirations for co-governance in the environmental/natural resource realm, the future of Napier Port, and the need to address climate change.

The first is the evident dysfunctionality of the Regional Council’s Regional Planning Committee, whose Māori co-chair recently called for HBRC’s elected councillors to be replaced by commissioners.

The second involves how best to guarantee the future viability of Napier Port as a cornerstone asset, in a manner that also yields the greatest financial security and benefit for the ratepayers of Hawke’s Bay.

The third, coping with climate change, might require politically charged adaptive responses much sooner than we think (what we grow, our consumptive behaviour, protecting our personal property and community assets), even in the next decade, as the indicators of global warming impacts worsen and accelerate almost daily.

Each of these issues will be rationally and emotionally challenging to the public and their elected representatives.

And each will be covered in depth by BayBuzz. Stay tuned.

Political lessons:

1. The smaller the issue, the bigger the debate.

2. Persistence is a ‘must have’.

3. Citizens can win, but it’s up to you.

4. Courts are part of any strategy.

5. It’s better to be inside the tent looking out.

6. Sunlight is the best disinfectant.

7. Independent, fearless reporting is a ‘must have’.

8. Disputes over process are more bitter than disputes over facts.

9. Emotion trumps reason.

10. Or as Grouch Marx said: Politics is the art of looking for trouble, finding it everywhere, diagnosing it incorrectly and applying the wrong remedies.