Child poverty has received much focus recently in New Zealand, with the Child Poverty Monitor indicating up to a third of the country’s kids now live below the poverty line – defi ned as NZ households earning less than 60% of the median national income; so below $28,000 per annum or $550 per week.

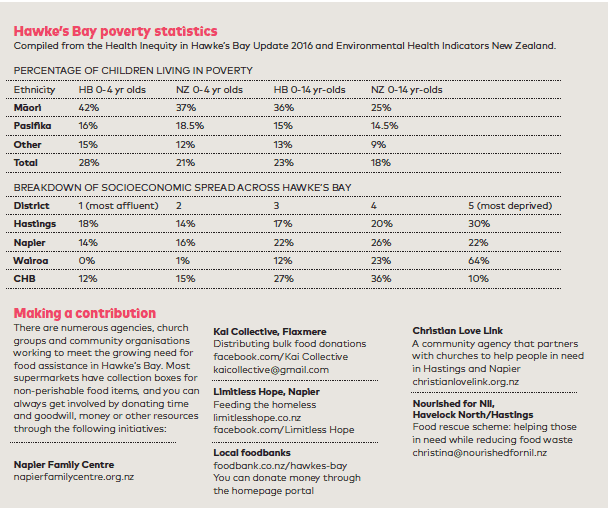

Hawke’s Bay’s median annual income is $29,000, and as the HB Health Board reported in October, 28% of all Hawke’s Bay residents place in the lowest deprivation quintile; 8% higher than the national average. (See table.)

Putting food on the table

While poverty indicators may vary, the reality is that for many of our families, making ends meet is a grinding challenge.

While my own quick survey of local primary schools suggests that a raft of government, sponsor-supported, and charitable ‘food in schools’ programmes (creatively adapted and inclusively integrated into each school kaupapa) are ensuring no child need go hungry at school, on the home-front it’s often a diff erent story with parents not always able to put food on the table.

Dame Diane Robertson, former CEO of Auckland City Mission, initiated the Family 100 Project to counter what she perceived as a paucity of work being done to understand families in poverty. For the ACM study, 100 Auckland families were interviewed by on-the-ground staff every two weeks for 12 months over 2013-14.

Hawke’s Bay’s median annual income is $29,000, and as the HB Health Board reported in October, 28% of all Hawke’s Bay residents place in the lowest deprivation quintile; 8% higher than the national average.

They found that families in poverty spend 60% of their time food-seeking, as they trek through the hoops of multiple agencies, and the rest in a cycle of managing debt, with little energy left for work or creative solutions. Of those doing the “hunting and gathering”, says Robertson, 90% are women without partners who support them, however that might look officially on paper.

Margot Wilson, services manager at Heretaunga Women’s Centre, suspects the situation in Hawke’s Bay may be similar.

Getting food assistance

Figures for Work & Income food grants for the East Coast region (from CHB to Gisborne) show that while numbers spiked towards the end of 2015, applications approved for WINZ food assistance across Hawke’s Bay have remained relatively consistent over the last three years, with 18,711 grants given in the year ending September 2016, to the tune of over $2 million.

The main community foodbanks in both Hastings and Napier show similar consistency, with around 4,500 and 4,220 people assisted in 2015-16, respectively, and the number of emergency food parcels (about 2,600 combined) on par with the previous few years.

The Salvation Army, however, reports that the downturn in the rural economy and an increase in housing costs have led to a rise in the number of people needing food parcels from their service. Across Napier, Hastings and Flaxmere, the number of food parcels distributed by the Salvation Army went up 32.5% in 2016, compared to pre- Christmas fi gures in 2015, with 550 new families requiring assistance.

Waipukurau Foodbank, which served 1,176 people through 400 or so parcels (2015-16), notes more families with young kids are seeking food assistance, and the size of family units requiring food are noticeably bigger. “We’re seeing homeless in CHB which we haven’t seen before; there are waiting lists now at the motor camps.”

To receive food assistance, people are usually directed fi rst to WINZ for a food grant (the fi rst two can be done via telephone, thereafter in person). While you don’t have to be on a benefi t to apply, you do have to be an NZ citizen or permanent resident and have a fi xed abode. The food vouchers are income and asset tested.

If you have been declined by WINZ, there are a number of foodbanks to approach, each with their own structure, criteria and opening hours. Some can only be accessed through agency referrals, or a budget advisory service; most request a letter from WINZ. Some are strict on the typical cap of 2-3 parcels per family, per year; others more fl exible. You may have to apply in person in the morning and then return in the afternoon to pick up a parcel, or it may be delivered to you. It’s harder without an address.

Then there are other smaller, less formal food collections, charitable groups and neighbourhood initiatives who may help, and a couple of regular drop-in meals: Tuesday evenings at the New Hope Community Church in Hastings, Friday every fortnight at the Sallies, Green Meadows.

Emergency relief

Napier Community Foodbank’s ‘four-day emergency relief’ packages are “well- balanced”, and tailored to the size and needs of each family, director Maggie Ronchi explains. The foodbank buys in perishable food items like fresh vegetables, eggs and UHT milk, but no meat products – “too risky”.

They also put together food parcels for those “living rough”, catering accordingly with food that doesn’t have to be cooked and with items like can-openers and plastic cutlery.

This past year, Kiri tells me, there have been “more kids than we’ve ever seen. We get kids walking in from Maraenui for a feed; they’re not necessarily homeless, but they’re hungry.”

The foodbank (established 1988) doesn’t have any direct contact itself with applicants, who are referred by health and welfare agencies for consideration. The agencies themselves distribute the parcels, and the depot is at an undisclosed location, mainly to protect the wellbeing of the 70+ volunteers.

Working from a comprehensive data base, “We have a fairly good feel for who the people in need are.” People can access up to two parcels a year if they have entitlements, and a third through an accredited budgeting service.

“It’s not a perpetual hand-out,” Ronchi insists. The parcels are “just to take the pressure off ” while other solutions are found.

Ronchi believes 90% of applicants are “genuine cases” who are usually extremely, even tearfully, grateful for the assistance.

Funding comes through personal donations, the support of Napier City Council, Lotteries and organisations like the Hawke’s Bay Foundation, bequests, community groups and the involvement of all the local churches.

“We operate in a really generous community,” says Ronchi, with many people donating items at supermarkets and other collection points, and some paying regular automatic payments each week.

Feeding the homeless

Kiri Swannell is the Warehouse National Community Hero 2016 for her work with the vulnerable in Hawke’s Bay, namely the homeless and mentally unwell. She began Limitless Hope in 2013 to provide emergency shelter in Napier; last year she helped 90 people off the streets.

On Monday evenings, she and her husband, Kevin, with a crew of volunteers, run a soup truck in Clive Square, which caters for up to 70-80 people per week, sometimes 120, once 200.

When they began, they were funding it for $120 per week from their own pockets, but they now receive grants and donations, with plans for the soup truck to be fi nancially self-sustaining.

This past year, Kiri tells me, there have been “more kids than we’ve ever seen. We get kids walking in from Maraenui for a feed; they’re not necessarily homeless, but they’re hungry.”

“Generally people are not too bad, they can get by. We notice an increase in need when the season’s finished and they start to run out of the dollars they’ve stored and get caught in the welfare rigmarole.” Pastor Andrew Reyngoud, Flaxmere Baptist Church

As we were there, a woman queued for her first Limitless Hope meal, taking food for her three kids who were waiting in the car – her plan for the night involved parking up on the beach.

But “It’s a lot more than meeting someone’s physical need,” explains Kevin. The soup truck fi lls a gap in connectivity. Regular volunteers include a nurse, a mental health worker, a social worker, a doctor, who use the opportunity to check in with their clients, “meeting them where they’re at and on their terms.”

“When we started four years ago, one of our objectives was to bring awareness and engagement to the community on the issue of homelessness and hunger.” Another was purpose – one of the young volunteers dishing out, queued himself for a year before being in a position where he could turn around and help others.

As for genuine need versus those just in it for a free meal, Kiri’s answer is simple: “Everyone has a need, and it may not be food. You have to give unconditionally; you can’t keep going otherwise.”

Building community resilience

Pastor Andrew Reyngoud, who is active through the Flaxmere Baptist Church in a number of food initiatives, believes that to eff ect change, you have to have “ladders for people”, which means collaboration and inclusion, not segregation.

He points to the five acres of community gardens adjacent to Te Aranga Marae. Set up by the U-Turn Trust in 2009 on the back of Henare O’Keefe’s ‘Enough is Enough’ hikoi, the gardens have been enormously successful in both nourishing people and engaging the Flaxmere community to rebuild itself.

The Flaxmere ‘food cupboard’, homed at Reyngoud’s church, is a combined Baptist and Anglican eff ort. “We have a broad protocol: if you’re local and in need, you come”, no WINZ letter required, and while, ideally, people would receive at most one food parcel per month, “if circumstances are diff erent, we’ll do it. We put safeguards in place so we don’t get too ripped off , but we’ll never turn people away.”

They give out about 500 basic food parcels per year, and Reyngoud observes a clear correlation between demand and the fl ux of low-paid, seasonal work. “Generally people are not too bad, they can get by. We notice an increase in need when the season’s fi nished and they start to run out of the dollars they’ve stored and get caught in the welfare rigmarole.” And again, when school starts back in February and the packhouse jobs are just starting up; people have to come off the benefi t but regular shifts haven’t yet kicked in.

Flaxmere Baptist Church also runs a six- week basic cooking class per term, cleverly timed to coincide with the foodbank slot on a Thursday morning so people can smell the cooking and be inspired to learn. “Food parcels help with the immediate need” but the aim is for people to be able to help themselves

The classes are free, the ingredients (and start-up equipment kit), are provided, and people take the meal and dessert they’ve cooked home to share with their families. It’s been “very well received,” says Reyngoud. “You see in people the confi dence they gain” and the eff ects “cascade down”. The best advocates are enthusiastic kids who love what their parents have cooked, and the people who have been on the course themselves, including one of the current cooking-class coordinators.

In early December, the church is transformed into a hub of bustling goodwill, as food is packaged and presents wrapped for the annual HDC Christmas Cheer Appeal, which serves 550 families throughout the Hastings district, involving 20 diff erent agencies – there’s a similar programme in Napier. Originally organised by Hastings District Council (still the main funder), the Christmas hampers are now coordinated by the Baptist church; Reyngoud’s wife, Jo , does the logistics.

Kai Collective: grassroots distribution

Andrew Reyngoud is also coordinator of the Kai Collective, a cross-agency organisation “connecting source with need” that facilitates the distribution of bulk donations of food around Hawke’s Bay: a glasshouse of tomatoes – “before they let the pigs in they let us in to harvest what was left”; pallets of produce from Wattie’s when there’s been a labelling error, for instance; the remainder from a fruit and vegie shop in liquidation.

“We then scale our stuff depending on size,” explains Reyngoud. “We use the ‘Little Red Hen principle’: the people involved doing the work [the various church and community groups], their organisations get the fi rst cut. Then we’ll kick it out a little wider, if it’s a bigger donation, to the food banks, Women’s Refuge etc, and then widen out further still. Once we got given a truckload of vacuum- packed corn, 10 pallets. We ended up taking it round to the marae, and it was all gone in a couple of hours.

“It’s a strength-based approach: you look at what you have and how you can apply it to the need presented.” The fluid, ad hoc nature of Kai Collective enables plenty of autonomy for the agencies involved: “The only rule is they can’t sell the food on, but it’s entirely up to them how they distribute it within their own protocols.”

Kai Collective, established in 2012, and supported from the side-lines by Hastings District Council, has been a successful model of grassroots organisation and an important piece in the picture of community resilience.

“The sense of hope and possibility in Flaxmere is huge,” says Reyngoud. “If there is something I would want to turn the volume up on, that would be the one: hope.”

Food rescue project

Meanwhile in Havelock North, Christina McBeth, who sits on the Napier Foodbank board, is hoping her food rescue project, Nourished for Nil, will be up and running in February, with the objective to help those in need while also reducing food waste.

Inspired by the Free Store, which operates out of a shipping container in downtown Wellington, and using the prototype of Just Zilch in Palmerston North, McBeth, her co-pilot Louise Saurin and their volunteer team will be sourcing leftovers from cafes, caterers, bakeries, supermarket perishables, and surplus or imperfect produce, to stock the shelves of their central Hastings ‘shop’.

They plan to open fi ve evenings a week, 5-7.30pm initially, and will welcome anyone, no judgement, says McBeth. For no one is immune from times of hardship, however they present.

“Food is premium, but we’re not taking away from existing initiatives,” she assures me, “we’re just creating another avenue.”

While premises and funding options are still in the pipeline, support so far has been “huge”, with Havelock North eateries, for example, overwhelmingly positive in their response. McBeth is quietly confi dent Nourished for Nil will have “a snowball eff ect”. “It’s been a very successful model, both around New Zealand and overseas; there’s so much potential.

“I know food hand-outs are not the answer to poverty, but it does create some security around the most vulnerable in our society: the children. If it means parents aren’t so stressed and can feed their kids, then we will have made a small dent.”

Run on volunteers and kindness

In the face of hard statistics and diffi cult realities, it is heartening to hear of the work being done by those quietly committed to making a diff erence, however small, and to sense the thrum of goodwill behind these initiatives, all of which are run on volunteers and kindness.

It is clear that the Hawke’s Bay community cares about hunger and is not prepared to sit back while others go without. Behind the scenes there are hundreds of volunteers right across the region busy collecting, cooking, distributing food to those most in need.

And it would appear, that while the chronic issues of poverty are a real and pressing concern, the immediate need for food is being met, one way or another, on a case-by-case basis, through charitable organisations, church groups, iwi, the generosity of neighbours, creative resourcefulness, and collaborative process.

But food is an ongoing, everyday necessity, and the struggle for many continues.

Kylie duffy need help with food plz can u ring me on 0226900903

hi everyone!!in need of any help and support for food assistance please would be so grateful for anything thank you for taking the tome to read my messages.

big thanks

Hi just asking do you do food parcel an delivery to people I am finding it how to get food for me and clothing for me and linen for me like you’re not going through wins will not help at all

For food assistance, try Nourished for Nil, with locations in Hastings, Napier, Flaxmere, Camberley: https://www.nourishedfornil.org

For other assistance, try Heretaunga Women’s Centre: https://heretaungawomenscentre.nz

Hi I am asking about a food parcel I need help with food I am a single person but I have kids on the week end I don’t drive a car