The Government recently released its first National Climate Risk Assessment, which will be updated every six years. Within two years, a ‘national adaptation plan’ must now be produced, and implementation of it will be monitored and evaluated by the new Climate Change Commission.

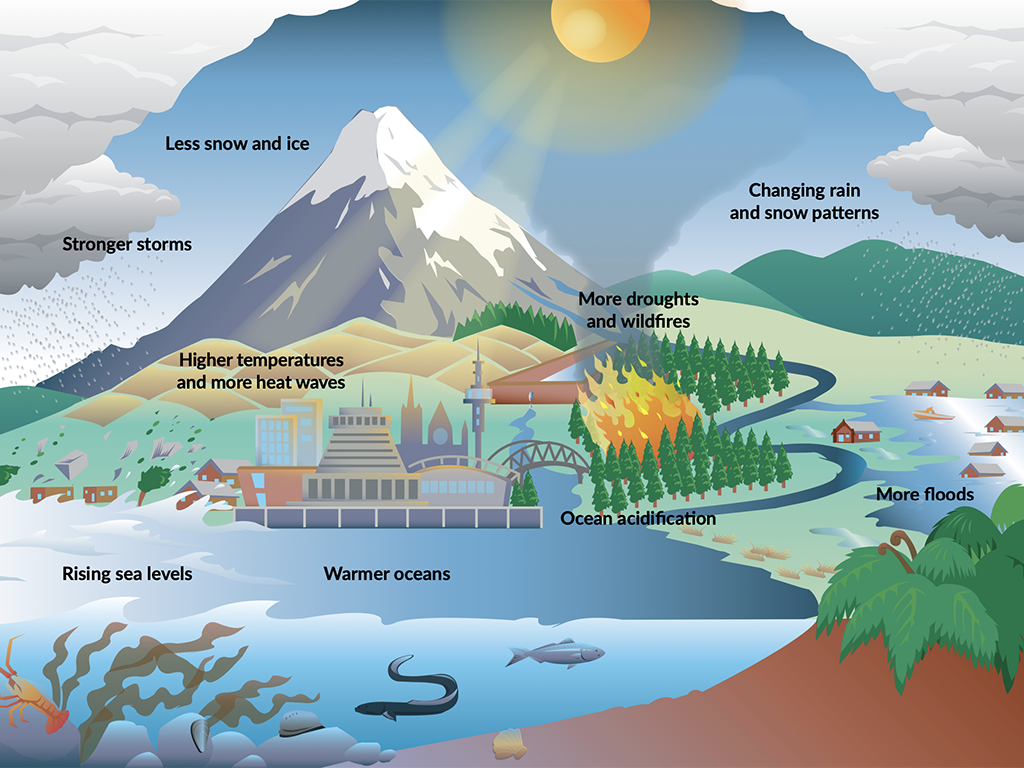

The Risk Assessment is predicated on these trends identified by NIWA:

- In the last 100 years, our climate has warmed by 1°C. If global emissions remain high, temperatures will increase by a further 1°C by 2040 and 3°C by 2090, with the greatest warming likely to be in the northeast.

- In the last 60 years, sea levels have risen by 2.44 mm per year. If global emissions remain high, sea levels will increase by a further 0.21 m by 2040 and 0.67 m by 2090.

- Extreme weather events such as storms, heatwaves and heavy rainfall are likely to be more frequent and intense. Large increases in extreme rainfall are expected everywhere in the country.

- The number of frost and snow days are projected to decrease.

- Drought is predicted to increase in frequency and severity, particularly along the eastern side of the Southern Alps.

- Wildfire risk is predicted to increase.

The Assessment identifies 43 priority risks; the ten most significant are described in this table:

The highest ‘Urgency’ rating is 94, with Urgency determined by the degree to which action is required in the next six years.

Of interest to an agricultural region like Hawke’s Bay, is Risk E3 related to the primary sector, given an Urgency rating of 81. Here’s the full description (I’ve left out the research citations that support these predictions):

“The primary sector faces risks from extreme events and ongoing, gradual changes. Climate change will reduce the quality and quantity of output across many areas including horticulture, viticulture, agriculture and forestry. Changes in temperature and seasonality influence maturation, length of growing season and the quality (size, shape, taste) of horticulture products; the distribution of pests and diseases and the efficacy of some pest control agents.

“The amount of land suitable for primary industries will decrease as sea levels rise and low-lying coastal areas become affected by inundation and groundwater salinisation. The impacts will increase over time. Some impacts are already being felt by the sector, for example, pressure on water availability. The Māori economy is focused on primary production industries like dairy, horticulture (especially kiwifruit) and forestry. Reduced production and profitability would have a significant impact on economic return to Māori landowners and Māori working in those businesses.”

The Assessment also noted as some opportunities from climate change, including these in the primary sector (again, with research citations deleted):

- Kiwifruit: Warmer summer temperatures are likely make more areas of the South Island suitable for cultivation. This is likely to be offset by some areas becoming less productive.

- Apples: likely to flower and reach maturity earlier, with increased size, especially after 2050.

- Grapes: Central Otago is currently the southern margin for cool-climate wine production. Wine grapes in this region will benefit greatly from warmer, drier conditions.

- Horticulture: New species may become viable.

- Plantation forestry: Growth rates (mainly Pinus radiata) are likely to increase due to higher CO2 levels and wetter conditions in the south and west of New Zealand. Warmer temperatures can also stimulate decomposition of soil organic matter and mineralise more nitrogen to further boost the nutritional status of trees. However, fast-growing timber can reduce timber strength.

- Pasture: Seasonal pasture growth may increase under some scenarios and in some areas. Seasonal average growth rates show consistent, large increases in winter and spring, as expected with warmer conditions and an extended growing season.

- Fisheries: Increase in primary productivity in shallower surface layers is likely in southern New Zealand waters.

“Productivity yields may increase for certain species due to more optimal growing environments. Higher average temperatures are associated with faster maturation, leading to an earlier harvest. Higher CO2 concentrations will increase crop growth rates.

“However, these scenarios assume a system where nutrients and water supply are not limited, and do not consider complicating factors such as pests, extreme events and competition for dwindling resources. Increased crop yields would result in an increased demand for water, creating a greater reliance on irrigation systems. A change in mean average temperature may also allow for the extension of existing species range and the introduction of new types of crops, although, as noted for kiwifruit, this may be offset by some areas becoming less productive. There may also be an opportunity for diversification into new areas and/or species of mahinga kai (food provisioning).”

This is it folks … the Government’s best estimate of how climate change will affect us. Daunting? Perhaps we best just deny it’s all happening.

Highest rated risk (coming in at 93) – water supply. Hopefully HBRC has a comprehensive programme of work to support an appropriate and balanced suite of solutions and interventions to address this.