Earthquake and tsunami experts are using the East Coast as a giant laboratory, probing, listening and measuring the rumbles and shifts in the tectonic plates and wondering, not if, but when, the patient will have a seizure.

Apparently all the symptoms are there and the world is watching, with those of us who live along the coast urged to prepare for the worst; to train our muscle memory to grab the essentials and head for the hills at short notice if the spasm is long and strong.

There are few written records of tsunamis smashing into the Hawke’s Bay coastline, although there’s geological evidence it happens about every 900 years. Minor structural impacts were reported in 1960 and 2010 when larger than usual waves swashed our shores after high-end quakes struck Chile.

New Zealand has had 10 tsunamis higher than 5 metres since 1840, the Gisborne tsunami on 25 March 1947 was 10 metres high.

I was reluctant when asked on World Tsunami Awareness Day to write a feature about the latest science surrounding our neighbourhood Hikurangi fault and growing rumours of an overdue mega rumble sending a destructive deluge toward our coast.

I have an aversion to disaster movies, The Day After Tomorrow, San Andreas, Cloverfield, Towering Inferno, Jaws…the genre is a giveaway; it never ends well, although Hollywood always finds some cheesy romance to offset the destruction and adrenaline pumping tension.

TV, YouTube and Facebook clips of the aftermath in Sumatra in 2004, Samoa in 2009, Chile 2010, Japan in 2011 and Indonesia in September 2018 have shown clearly the destructive power of nature without having to fictionalise anything.

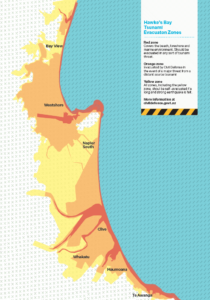

Despite living on the coast with evacuation zone signs around the corner and having seen large council maps showing the potential path of shock wave devastation, I was in denial.

Facing our fears

Being a diligent journalist, I was forced to face my fears. What was this new information; was the big one coming soon?

The HB Emergency Management team’s presentation to the HB Regional Council at the end of October was the start of an information tidal wave of links and reports I needed to wade through before interviewing hazard reduction team leader Lisa Pearse.

I was feeling a little edgy as days before my interview there had been a cluster of quakes off California’s San Andreas fault and a deep and wide 6.2 quake off Taumarunui that rocked my home office.

Was this a potential trigger for wider activity? That’s the question Pearse and her colleagues are pondering, since the swarms of quakes off Porangahau following the 2016 Kaikōura earthquake, something not seen for at least 15 years.

“Off the coast of Gisborne…Porangahau…Kapiti and Kaikōura… a slow slip or a series of slow slip events…lit up at the same time.”

Pearse is concerned we may have underestimated how tsunamis form and perform, particularly after the last one in Japan overturned a lot of assumptions about subduction zones. “It was a lot bigger than they ever anticipated, overtopping their tsunami defence walls.”

A main concern for her team and the East Coast Lab: Life at the Boundary project, which she and fellow scientists initiated in 2014, is the fact that the subduction zone south from Cape Turnagain is locked and pressure is building.

“That’s a worry because the plate keeps moving and putting pressure on that locked part of the plate boundary and one day that pressure will be released through a big earthquake.”

Assessing the risks

Subduction zones are where most of the world’s deadliest earthquakes, volcanoes and tsunamis occur, and scientists are signalling that we need to be aware of this risk.

Pearse says Kaikoura is at the southern end of that subduction zone which then flows into a network of faults including the inter-related Hope and Alpine faults.

The locked part sits right under Wellington extending through to the bottom part of Hawke’s Bay. “If we did have a big earthquake on that plate boundary the whole of the North Island would be affected.”

The “slow slip phenomenon” was uncovered by geoscientist and GNS Science project leader Dr Laura Wallace in the Hikurangi subduction zone 15 years ago.

Dr Wallace’s efforts have placed New Zealand at the global forefront of studies on tectonic plate boundary processes and resulted in more than $60 million in international research funding being raised to investigate what’s going on and the potential threat it poses.

Lisa Pearse, who’s worked in emergency management for around twenty years, says this increased scientific focus has resulted in a “fundamental change in thinking and in understanding what this fault is capable of”.

While attending the Transformation, New Zealand Emergency Departments conference in Taupō in September, she heard Dr Wallace describe the Hikurangi subduction zone as “the master fault in New Zealand”.

Unlike the Alpine Fault, its buried underwater like a hidden mountain range. “We don’t actually see it, so we probably tend to ignore it at our peril.”

Dire possibilities

She says science papers a decade ago mostly focused disaster risk assessment on the Alpine Fault, volcanoes and the Wellington Fault. “Hikurangi is almost mentioned as an afterthought when it came to the risk of tsunami.”

After Kaikōura there were forecasts about the increased risk of a quake around 7.8 on the Richter scale and while that concern has eased, no-one’s breathing easy yet as international evidence still hints at dire possibilities.

“That’s why the scientists are trying to get a better understanding what these things mean… the reality is, the risk is still 2.5% greater than when Kaikōura happened.”

Pearse says geological evidence suggest New Zealand faces similar risks to Japan, but they’re far better prepared. “We have to learn from science what Japan has now committed to long-term memory over 1,300 years, including historic markers along the coastline.”

The force of the last big one resulted in an international collaboration of tsunami scientists, and the formation of the Geodynamic Processes at Rifting and Subduction Margins project or Geoprisms.

The US-based project chose three global sites where scientists are now working together – Cascadia in the west of North America, the Alaskan and Aleutian margin, and the Hikurangi margin extending from Poverty Bay-Gisborne down to the lower North Island.

A key reason Hikurangi was chosen was the Earthquake Commission’s investment in the nationwide GeoNet system which allows scientists to use GPS to locate what’s happening with our land mass.

From October, as part of a multi-year process, a number of research ships have placed instruments off the coast of Gisborne, Hawke’s Bay and Wairarapa with local scientists joined by those from Canada, the UK, the US and Australia to better understand the earthquake and tsunami potential.

Off the coast of Hawke’s Bay two ships including NIWA’s R/V Tangaroa deployed “a whole bunch of really expensive, internationally funded, equipment”.

Sensing the seafloor

GNS Science project leader Dr Wallace says the research is a priority for New Zealand scientists with the instruments recording hundreds of small earthquakes that cannot be accurately located with land-based technology.

Among the instruments are 19 seafloor pressure sensors, that record upward or downward movement of the seabed and can detect slow motion earthquakes offshore. There are also eight ocean bottom seismometers and two precision arrays of seafloor transponders tracking horizontal movement of the seafloor.

All of this is to ensure we are better prepared for the worst-case scenario. Concurrently every effort is being made to strengthen and streamline our risk management, including the GNS Science open-all-hours geohazard risk monitoring centre.

The emergency mobile alert system that can reach cellphone users based on their geographic location and risk…if the phone’s on and within coverage…is also being enhanced.

The baseline though is the Civil Defence PR campaign launched in 2016 – if it’s “Long or Strong, Get Gone”, which carries an important sub-text. We cannot rely on sirens, loudspeakers, the radio, the web or our neighbours … we’re on our own if the big one lets rip.

We’re told 90% of coastal dwellers have got the message, but Pearse isn’t convinced, with evidence showing too many people fuss around looking for things and waste precious time.

The fact is we may only have 15-20 minutes before the wave impact pummels and pushes through coastal communities and that’s a real life challenge for anyone, particularly the elderly and infirm.

There’s talk of community evacuation plans but that conversation is still evolving, and even emergency services are being advised to get out quickly so they can be available in the aftermath.

If the quake is strong enough to make you unsteady on your feet; there’s a sudden sea level fall or rise, or the sea is sounding like a jet engine, don’t join the ‘oooh aaah’ crowd thronging to the beach for a selfie, evacuate all coastal zones for higher ground or as far inland as possible.

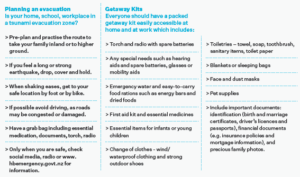

Plan by having your essentials – including medication, torch, radio, phone, documents – in a grab bag. Rehearse the journey by bike or on foot during the day and night so your escape is more intuitive.

If and when the rock ‘n roll nightmare eventuates, at least you can say you’re prepared. As for me, I can no longer bask in the safety of my own ignorance.

I have to wonder where the heads of NCC are at, when they are prepared to spend approximately $4m on building a “revertment” (effectively a sea wall) to protect 10 properties at Westshore. That they can take a business case that says 95% of benefit to private landowners and 5% public and flip it to 95% public 5% private.

Given the environment we are in is this the best use of public funds?

Are they truly considering what is really needed in terms public benefit and safety?

Are they spending money in a way that will best save lives and promote resilience in the face of inevitable natural disasters?

I note that majority of significant roads lie approximately on a North / South axis. Cross multipe creeks and streams.

How is Napier placed to evacuate 40,000 people based on the risk maps?

Should we be continuing to allow housing developments below 10m above sea level?

There is a reason why the Japanese in coastal areas have for decades built schools in the hills.

Would be good to see some discussion and commitment to addressing these issues by NCC and Regional Council Candidates in the upcoming local body elections later this year.

Pj is right. NCC, or rather Hawkes Bay Emergency management have absolutely no clue in regards to preparing people for community resilience. In fact, a large proportion of the population believe that the sirens will sound for a tsunami, when in fact they won’t. According to HBEM website, the sirens will only be used to warn people to tune into a radio station to find out what the emergency is and that could be anythingnfeom a volcanic eruption to civil unrest. This needs to be addressed, and urgently it seems.

Get Gone!!

To where ask the 130000 Hawkes Bay folk.

Given an earthquake has triggered local tsunami waves from Hikurangi trench the roads will be impassable. And where exactly are we to be Got Gone at? Bluff Hill seems about 2 to 3 times expected wave height but it’s access is first in line and that 5 to 8 minutes will go very fast. What does tens of thousands of people streaming towards the bowl of hills behind the wave collection basin we live and work in, look like?