We’ll come to Hawke’s Bay in a moment; first the national context.

Emergency housing demand is greater than ever, waiting lists for social housing are longer, and the price of buying and renting continues to hit record monthly highs.

There are stories about working poor, made so by having to spend up to half their weekly earnings on rent, and how a whole generation of young New Zealanders will likely be renting all their lives, unlike their home owning parents.

Rack-renting landlords are getting a battering, and the Government is being criticised for doing too little to tether the boom.

Opinions on causes and solutions abound. Agreed by all is that we are a country obsessed with residential property ownership.

A popular trope is that Bob Jones planted the seed in 1977 with his book, Jones on Property, and with his ‘how to’ seminars that followed. When the Stockmarket crashed in 1986, many burnt investors turned to property, never returning to shares.

In January 2021, 30% of house buyers were investors, 21% were first home buyers, 49% were owner occupiers moving to a new house. (CoreLogic))

There’s no doubt investors skew the market and drive up prices, and as they compete in the same price range as first-home buyers, every purchase for rental deprives a first-home buyer.

If investors weren’t a component in the market, there would be 30% more supply of houses, and we wouldn’t be experiencing a property boom nearly on the scale we are today.

Lack of supply is the major factor in house price and rent inflation. And the reasons for there being more buyers/renters than sellers/landlords in the current market are: failure of successive governments to facilitate more house building, historically low mortgage interest rates, a decade of high immigration, Covid returnees entering the market, and for investors, rentals offer better returns than depositing in the bank.

Steps have been taken by Government to intervene in the market by increasing the deposit needed by investors to 40%, and they must own five years before selling, or pay income tax on capital gain. More restrictions on investors have been signaled but not yet announced.

The Government assists first-home buyers with First Home grants and loans, and the KiwiSaver first-home withdrawal scheme, with deposits as low as 10%.

So that’s the national context, now let’s look at Hawke’s Bay.

Land available

But if increased supply is the key to stabilising the real estate market, building more houses is what’s needed. That’s happening at speed on existing subdivisions in Hawke’s Bay, both in the private sector and through Kāinga Ora – Homes and Communities.

Land supply, while currently ample, is limited in the future by the need to protect the productive soils of the Heretaunga Plains.

Both Hastings District Council (HDC) and Napier City Council (NCC) are encouraging greater density within existing boundaries, and partnered with the Regional Council, in 2017 agreed to the current plan for future growth until 2045, the Heretaunga Plains Urban Development Strategy (HPUDS).

Mark Clews, principle advisor district development, started at Hastings City as a town planner in 1985, and has been involved in the evolution of urban planning strategy from the outset.

“After amalgamation in 1989 both Councils did twenty-year strategic plans for urban development. Napier had NUGS, and Hastings had HUGS. There were five-yearly demand reviews to see if we were on track, and the 2005 review recognised HUGS was coming to the end of its life.”

As a way forward, discussions seeking a collaborative approach were initiated between Hastings District, Napier City, and the Regional Council.

“Getting all the ducks in a row for the necessary implementation actions to be put in place,” took five years.

In 2010 HPUDS was established with the purpose of providing comprehensive, integrated, and effective growth management strategy for the Heretaunga Plains.

“The approach was to protect the soils by intensification within boundaries and move away from big greenfields developments like Arataki and Lyndhurst, but with some smaller greenfields to round off the boundary.”

With protection of fertile soils being a key aim of HPUDS, ring-fencing urban boundaries, “is what councils are working towards”.

Arataki and Lyndhurst subdivisions in Hastings, and Parklands and Te Awa in Napier, were well underway when HPUDS was initiated in 2010.

The latest update (30 September 2020) on availability of greenfields subdivision sections indicates the current supply of zoned and serviced land is likely to be sufficient for 10 years. The calculation, based on the five-year average building rate, might be optimistic, because greenfield development builds over the last year to 18 months are more than twice that of the preceding two years.

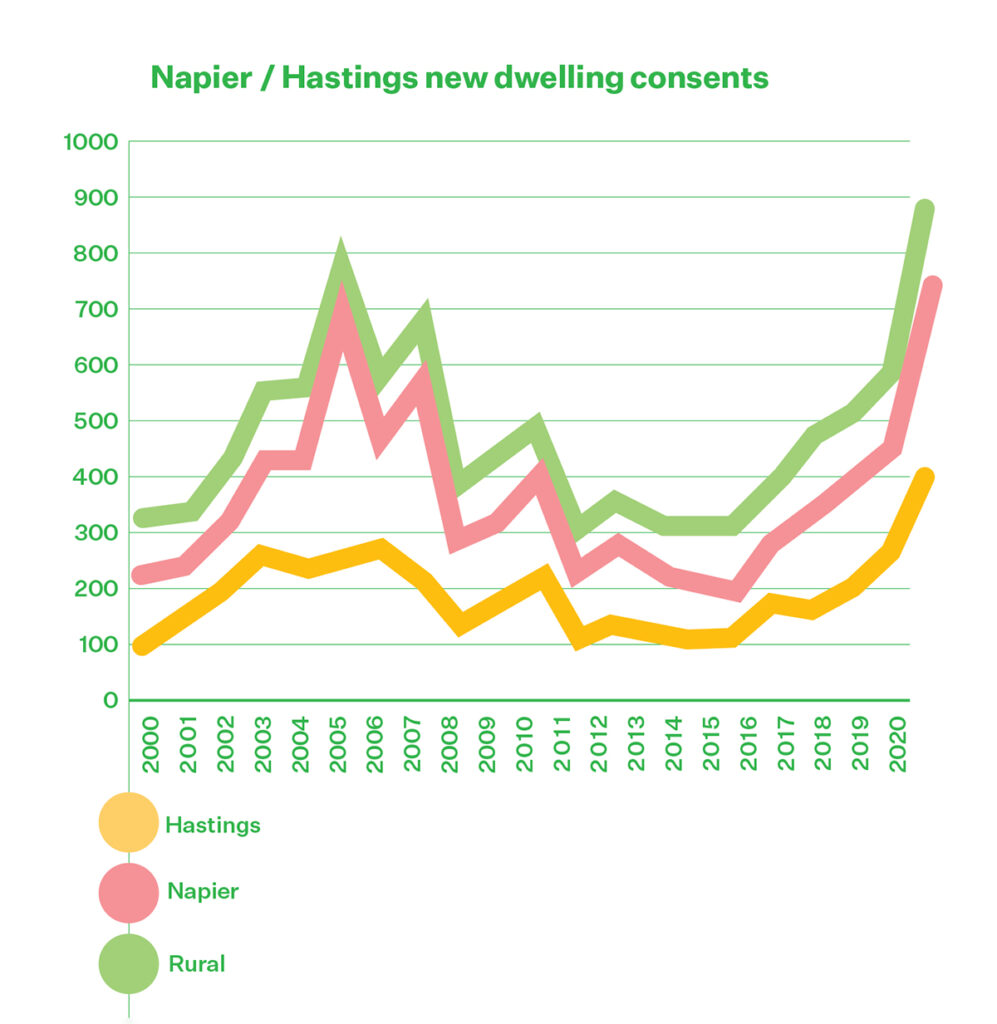

Mark Clews confirms, “There’s more growth than we expected,” and points to the 2020 building consents “being the highest for 20 years”.

Currently there are 225 sections available for building in existing greenfields subdivisions, and the capacity on land already zoned residential (but not yet to the stage of titles being issued) is 1,393 standard residential allotments.

Additional large capacity brownfield subdivisions (within existing boundary) planned for Hastings in the next two years are 340 lots in Iona Road, Havelock North, and 290 in Howard Street, Hastings.

In Napier, Richard Mennuke, director city strategy, recognises the importance of protecting productive soils, but points to other factors that must be considered in Napier.

“We’ve got a tsunami hazard and we’ve got liquefaction problems. All of the flat land is not ideal land for residential.”

He’s referring to Te Awa subdivision in Napier South, which is below sea level, and Parklands in Tamatea, which was a tidal swamp before being heaved up in the 1932 earthquake.

Napier City Council inherited Parklands from the Harbour Board in the 1989 amalgamation. Unable to find a developer for the subdivision, NCC assumed that role, which “has been good for the ratepayer because it’s an income other than rates”.

Mennuke inherited both subdivisions when he joined NCC in 2015. “We have to finish Te Awa and Parklands (10 years’ supply). Then we would like to go to the hills.”

Mission Special Character Zone was created in a district plan change in 2017 covering 289 hectares of land behind Mission Estate Winery.

“Council entered into a partnership, or memorandum of understanding, with Mission Holdings and used a design-led plan change to develop up to 600 sections. Next step is the development plans, which include subdivision design, roading, and provision of all services.”

Mennuke expects there will be “a mixed typology of housing” that might include high-density town housing on the land closest to the city, to large sections with panoramic views attracting premium prices.

A novel aspect of the development is a catchment basin for stormwater, which feeds a subterranean river flowing to the Heretaunga aquifer, eliminating the need to connect with Napier’s stormwater infrastructure.

HPUDS’ latest quarterly report estimates that the Mission, Iona Road, and Howard Street developments will likely provide a further 5-7 years’ capacity, while the remaining HPUDS capacity is expected to add another 15 years to the supply.

Intensification

It’s obvious supply of land is not a factor in the current property price explosion; however that availability is mostly in greenfields subdivisions, where sections average $300,000 and to build a three bedroom home costs $400,000. This sector of the market is well catered for, and construction on subdivisions is booming, but the entry price is prohibitive to most first-home buyers.

In an effort to encourage affordable housing, both Napier City and Hastings District Councils are promoting intensification in existing suburbs.

Napier’s Richard Mennuke points to “intensification on the fringe of the city within the walkable zone, so people can live their lives enjoying the city.”

He envisages 3-5 story apartments and town houses on the CBD fringe.

In an effort to pin down where such building is suitable, NCC is “entering into a spatial planning exercise which will basically be a big map showing what is going where, so we can consult, and reach agreement from all the stakeholders.”

Consultation on the spatial plan is in process and will be merged with the district plan currently under review.

Hastings District Council is actively encouraging residential intensification in existing neighbourhoods through Design Guide 2020, launched at a Building Industry and Land Development Forum on 10th February 2020.

The Guide provides useful ideas and solutions to common design and development challenges. By following the Guide, development concepts are more likely to have a smooth passage through the consenting processes.

Unlike Napier, where the CBD is compact with limited suitability for intensification, Hastings’ commercial zone sprawls along Heretaunga Street and fringes, with many buildings no longer fit for purpose.

HDC is encouraging developers interested in retro-fitting commercial buildings to residential, with incentives, including a proposal to provide some funding.

Napier-based architect, Sol Atkinson, is involved in several intensification developments, not only designing the houses, but also subdivision design.

“Increasingly we’re designing a subdivision layout working in cooperation with the client, surveyor, and planning consultant to optimise section sizes and the layout of sections. For example, orientating sites to the north with access from the south to maximise best use of the site.”

In Te Awa Fields he has designed “a little node of eight duplex houses which act as a keystone” to the entry to the subdivision. A bigger development is, “28 two and three bedroom duplexes, built by a private developer in contract with a social housing provider”.

As an example of intensification providing affordable housing on existing sites, he points to a 1600 m2 section in Hastings, where an existing four bedroom villa in disrepair is removed, and replaced with seven two-bedroom houses, four being duplexes. Another achieves eight houses on a corner site with similar sized plot of land.

“From one household of four bedrooms we achieve seven households with fourteen bedrooms.”

Building-cost efficiencies are achieved “through duplication and by leveraging the design and technology we have to make it as efficient as possible to do design variations and changes”.

Affordability

Affordable housing, both for ownership and rental, is the desperate need. Currently in Hastings, there are around 600 households on the social housing waiting list, and 1,700 people are in emergency housing, mostly motels, costing around $9 million last year.

An idea, born at a hui at Waipatu Marae in April 2018, and officially launched in December 2019, has made significant progress in delivering affordable housing.

Hastings Place Based Plan is a pilot scheme, the only one in the country to have all the relevant agencies sitting at the table: Hastings District Council, Ministry of Housing and Urban Development, Ngāti Kahungunu, Te Taiwhenua o Heretaunga, Kāinga Ora, Te Puni Kōkiri, Ministry of Social Development, Hawke’s Bay District Health Board and the Department of Corrections.

Iwi representation is a vital component in the success of the Hastings Place Based Plan as Māori disproportionally figure in those in need of permanent housing. Having iwi and hapū embedded in the urban regeneration process is a game-changer in providing homes for whānau.

The Ministry of Housing and Urban Development is responsible for policy, monitoring, and advising Government on strategy.

Kāinga Ora, formed in 2019 by merging Housing New Zealand, Kiwibuild, and HLC (Home, Land, Community) is focused on providing public housing, with a mandate to undertake urban development on its own, or in partnership with others.

Currently Kāinga Ora have around 150 homes completed or under construction in Hastings, and 31 new houses are being built in Maraenui, Napier. More are in the consenting process.

A model example of the coordinated agency approach is the 120 dwellings, Waingākau Village, at Te Aranga Marae in Flaxmere.

Hastings District Council is the consenting authority and infrastructure provider. Te Taiwhenua o Heretaunga (iwi social services provider) is the developer. Te Puni Kōkiri is offering pathways to home ownership with funding and rent-to-own schemes, and Government has provided funding to HDC to assist with infrastructure costs.

Waingākau offers a unique concept of co-housing, where dwellings range from one to three bedrooms, with the opportunity for intergenerational occupancy.

Clustered around communal open space, with vegetable gardens and a food forest, Waingākau aspires to be a village embracing Māori values of community.

Papakainga is another pathway to delivering homes for Māori by building on ancestral land. This ishappening apace at Waipatu, Waimarama, and Waiōhiki.

Another component of supply, which has for many years taken rental houses out of the market, is the provision of accommodation for the 4000 RSE (Recognised Seasonal Employer) horticultural workers from the Pacific Islands.

In August 2020 HDC addressed this with a variation to the proposed district plan to allow greater scope for employers to provide accommodation. Self-catering clusters on the sites RSE workers work can be greater than the previous 125m2 limit, and larger buildings will be allowed on industrial zones to house seasonal workers.

On yet another front, how much existing house stock will come to the market by retirees buying into the 800 homes currently being constructed in retirement villages in Napier and Hastings is difficult to determine. With a minimum entry point over $600k it can be assumed most of the new residents will be selling homes at the average sales prices or above.

Population growth

Lack of house supply in the marketplace is shared by every metropolitan area in the country.

In Hawke’s Bay, the current growth in the economy and population was not predicted. Addressing housing supply was not a council priority.

As Richard Mennuke points out, “For years Napier and Hastings were flatlining in terms of growth, and we responded to that.”

In 2009, Hawke’s Bay’s economic growth was minus 1.5%, sluggish for the previous and following years, recovering to 2% in 2020. Population growth 2006/2013 averaged 0.5% a year. In 2020 growth was 2%, the greatest increase on record.

Planners rely on data and, with the compromised 2018 census, no one foresaw the growth.

“We’re flying blind to some extent. It’s very hard to build a picture with anecdotal facts rather than real statistics.”

Mark Clews concurs. “The 2014-17 stats didn’t project massive growth.”

Council wheels turn slowly, restricted by rigid urban planning rules and consenting processes, making it hard to respond to rapid change.

However, with initiatives like the Hastings Place Based Plan, and Napier’s inclusive spatial plan, the councils are addressing the affordable housing supply.

Both Councils are currently reviewing their district plans, and enabling affordable housing by making it easier for developers, be they private or public, to build new, and reconfigure existing buildings, through more flexible planning rules.

However, Richard Mennuke casts a warning. “Fundamentally I see my role as a planner is to try and make a great city for everybody, and that means not just pleasing the developers, or the real estate sector, or even a desperate demand for more housing. We have to balance everything. There are lots of different pressures. We need to plan wisely and thoughtfully. But it strikes me it could easily flip into the opposite if we’re not careful.”

Back to the Beehive

So, if local councils are proceeding with felt urgency, what about Government? Here’s my view.

In April 2019, the Coalition Government rejected the Tax Working Group recommendation to introduce a Capital Gains Tax (CGT) on all property except the family home. In doing so they threw away a useful tool for dissuading speculating investors.

CGT was so unpopular, Jacinda Ardern neutralised it as an issue in the 2020 election by saying it wouldn’t happen while she was Prime Minister. That New Zealand is the only country in the OECD to not have CGT is an indictment on political courage. New taxes are never popular, but like the introduction of GST in 1986, concerns soon fade as the policy beds in.

There is a way the Government could introduce CGT by stealth: extend GST to include all capital gains, except the family home. Labour is sitting on a pile of political capital. It’s time to spend some in bringing fairness to the housing market. That speculators can buy and sell without paying any tax on their unearned profit, is grossly unfair to every wage and salary earner who pay tax on their earnings.

The hope for first-home buyers is that the market stabilises, and with Government intervention doesn’t spiral out of control again. In the meantime, increasing wages, without house price increases, will make home ownership more achievable.

Stabilising the rental market is easy. Introduce measures to control rents, which could include Rent Tribunal binding assessments, and increases in line with Consumer Price Index.

Aotearoa New Zealand has one of the highest income-to-house price ratios in the world. Simply put, it’s harder to buy a house here than most other countries. Decades of laissez-faire, free-market attitude towards the housing market by successive governments, has led us to where we are today.

Hopefully, the sixth Labour Government, can invoke the courage of the first, and regulate the property market.

After all, the Prime Minister has a photo of Michael Joseph Savage on her desk

If you buy your new home before you sell your existing one then the statistics will class you as an investor.

Excellent article wish other councils had this preparation

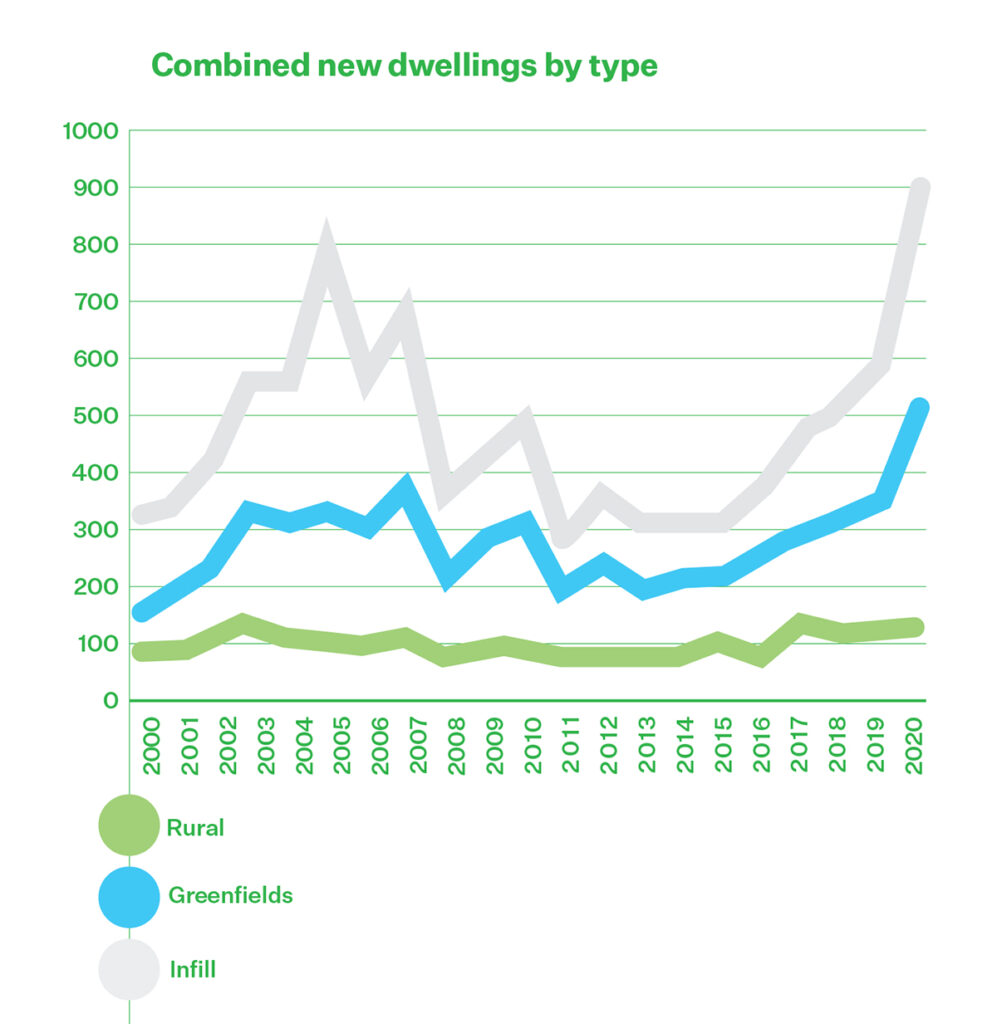

“Aotearoa New Zealand has one of the highest income-to-house price ratios in the world.” Surely this should be “lowest” income-to-house ratios. Otherwise a good and helpful analysis. Totally surprised to see the high level of infill housing right back to 2000, and the low level of HDC consents relative to Rural, given that so much of HDC is rural anyway.