Leading Change

Even as a die-hard coterie of global warming deniers, greenie-bashing farmers, and oil & gas advocates hang on to the past, events in the real world are outpacing them and rendering them irrelevant.

In every sector of economic endeavor, from high finance to on-farm practices, the smartest movers are embracing the realities – and opportunities – afforded by the accelerating transition to a new economy based on renewable energy and environmentally sustainable land use, business practices and consumer preferences.

Card-carrying ‘environmentalists’ have led the way, but now critical leadership is coming as well from hard-nosed capitalist investors and financiers, major corporations, and formerly vilified institutions like the World Bank (which in December announced it would no longer finance oil and gas development).

I’m hopeful that we here in Hawke’s Bay – joining leading players in New Zealand – will play our part, reaping the benefits of a moral imperative. There’s nothing wrong with doing good and doing well.

I’m re-publishing here two examples of NZ leadership thinking, both first published by Pure Advantage (pureadvantage.org) … a beacon of provocative ideas.

The first is a group essay – a manifesto, really – written by Sirs Stephan Tindall and Mark Solomon and other trustees of Pure Advantage. They issue a clarion call for a NZ green economy … Our Chance to Lead.

Then follows Change Afoot Down on the Farm by Rachel Stewart. She gets down to ground level, looking at the exciting farming transformation underway at Crown-owned Landcorp – now branded Pāmu, Naturally New Zealand – which owns or manages about 125 farms on nearly 400,000 hectares throughout NZ.

What does the Pāmu brand promise? Among other things – “We never feed imported ingredients like palm kernel expeller (PKE) synthetic or artificial feed, GMO or antibiotics. Natural means there is no need for artificial flavours or additives to our products…”

There’s the future path of NZ farming.

Helping to bring that future to Hawke’s Bay farming will be the mission of the Future Farming Trust just initiated by the HB Regional Council.

In a nutshell, this project is about innovation, lifting the bar, and improving long-term competiveness – all in a Hawke’s Bay context. The Future Farming Trust, led by HB practitioners, will collect evidence of how leading farmers and growers in our region are achieving positive, balanced and integrated outcomes for their land and businesses. And translate this evidence into proven, accessible and achievable HB-relevant options that can help other HB farmers/growers to better their environmental performance while improving on-farm economic returns and resilience.

I have championed this initiative and will write more about it as the project gets underway.

Meantime, I hope this ‘big picture’ inspires you.

Our Chance to Lead

PURE ADVANTAGE TRUSTEES: ROB MORRISON (CHAIR), SIR STEPHEN TINDALL, SIR MARK SOLOMON, KATHERINE CORICH, PHILLIP MILLS AND GEOFF ROSS

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern made waves in the lead up to the 2017 election when she labelled climate change her generation’s ‘nuclear free moment’.

She’s right, of course. There’s never been a stronger moral imperative to tackle one of the greatest challenges humanity has ever faced. But taking action on climate change also presents enormous opportunities for New Zealand to build a thriving green economy and stay ahead of the curve as the world transitions.

The Government’s recent announcement to ban new offshore oil and gas exploration is just one step – but a bold one, and in the right direction. A lot of the negative commentary on the ban has largely ignored the game-changing opportunities an economic strategy based on the renewable energy industries of the future will offer us.

These opportunities are material. The Business and Sustainable Development Commission (BSDC) estimates the opportunities in the emerging clean energy sector to be worth US $605 billion to the private sector globally, by 2030. BSDC further estimates new opportunities in forest ecosystems globally represent up to $365 billion per year through 2030, electric vehicles represent $320 billion in the same time period, and energy efficiency in the building and construction sector is estimated to be worth up to $770 billion by 2030.

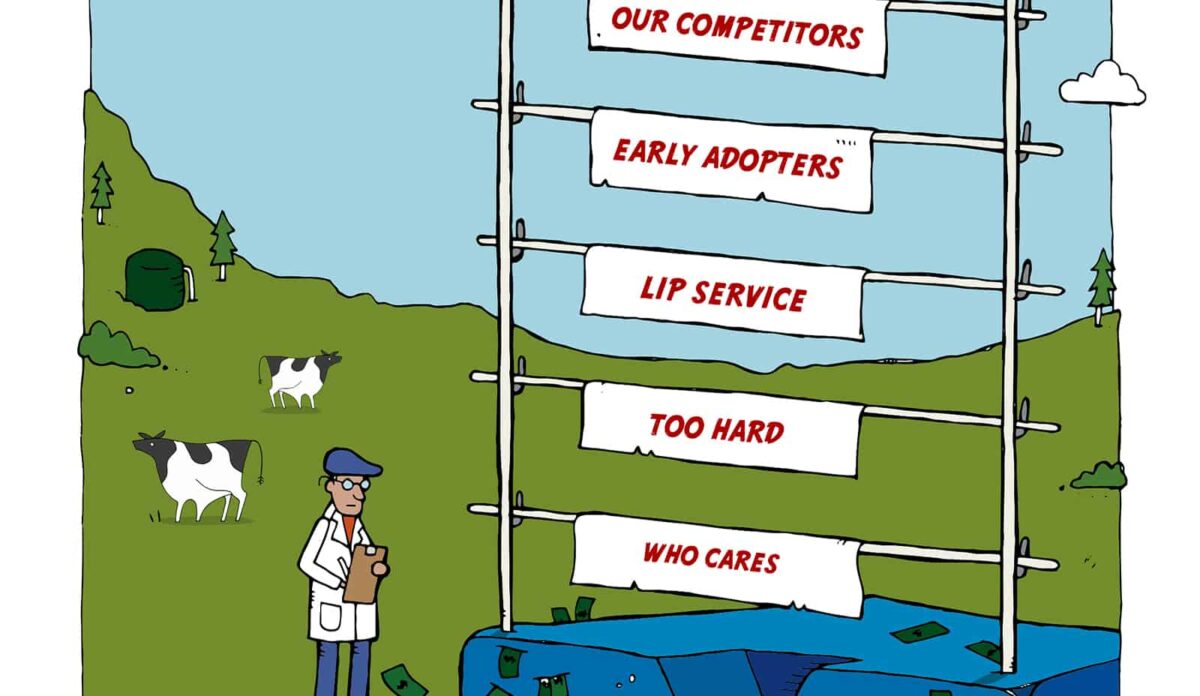

The report also estimates that first movers seizing these opportunities will have a five to fifteen year advantage.

Looking longer-term, PWC’s estimates for the World Business Council for Sustainable Development suggest annual sustainability-related investment opportunities in food and agriculture and forestry totaling $1.2 trillion per year and $200 billion per year, respectively, by 2050. According to the World Bank, if every country is to meet their Paris Climate Agreement commitments there is a $23 trillion dollar global investment opportunity.

By taking a strategic approach, New Zealand can lead in developing the industries that will contribute to the global economy of the future as well as drive our own prosperity, and at the same time show kaitiakitanga (guardianship) for our environment and encourage innovation and resilience in our people.

Some of our greatest economic opportunities lie in areas where we have core strengths and relative advantages, for instance in renewable energy, high value regenerative agriculture, biotechnology and forestry, biofuels and bio-products, in improvements in the built environment and infrastructure, transport, across the board efficiencies and electricity grid technology. The Productivity Commission’s draft report examining how New Zealand can transition towards a low emissions future while growing incomes and wellbeing found that the “emergence of new technologies and firms in the low-carbon sector will provide opportunities for employment, exports and productivity gains”.

There are also risks in remaining reliant on a high-carbon infrastructure. Fossil fuels are increasingly being seen as a financial liability. Conservative models indicate US $2.5 trillion will be wiped from global financial assets, between stranded assets and climate impacts. Major investors are making moves to reduce their exposure to climate risk as well as reduce the overall impacts of climate change. The Norwegian sovereign wealth fund, the world’s largest, has already begun divesting from high-carbon projects, and is making plans to remove all oil and gas projects from its portfolio. Last December, the World Bank announced that they’ll be ending financial support for oil and gas exploration.

In the New Zealand context, Westpac bank recently released a study in partnership with Vivid Economics and Ernst Young demonstrating we will be NZ $30 billion better off if we respond to climate change sooner rather than later. Chief Executive, David McLean, said: “This research demonstrates the importance of taking immediate steps to cut our greenhouse gas emissions. The alternative is waiting and taking action later, but that is likely to require more drastic changes in behaviour and over the long-term hit people harder in the pocket.” Westpac itself is reducing exposure to fossil fuels and investing in renewables, echoing a clear trend in the global finance sector.

The low carbon transition represents enormous opportunities and helps us manage enormous risks – but it must be done in a way that protects our people and communities. Ensuring that this transition is socially just and leaves no one behind will require careful planning, long term thinking, and sufficient runways for communities and sectors to transform. This position is supported by the New Zealand Council of Trade Unions (NZCTU). Executive Sam Huggard said: “The science is clear that there is no long-term future for oil and gas, that’s inescapable, and the quicker we can have a plan in place for transition, the outcome for the workers will be much, much better.”

The low-carbon shift comes with significant opportunities for employment, including boosting regional jobs. Around the world, countries investing in renewable energies show that job growth in the sector far outstrips that of future oil, gas and mining sector opportunities. The International Renewable Energy Agency has found that solar PV creates twice the number of jobs per unit of electricity as coal or gas.

In the US solar jobs are growing as much as 12 times faster than the rest of the economy. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, the two fastest growing occupations in America are solar photovoltaic installers and wind turbine service technicians. One in every 50 American jobs created in 2016 was in the solar industry, according to the Solar Foundation. Furthermore, solar installation and maintenance jobs are by their very nature local jobs, which can provide a necessary boost to regional employment.

Importantly, the benefits of the low-carbon transition go beyond employment and GDP. For instance, the Productivity Commission report identified the enormous opportunity that technological innovation holds in creating “dynamic and creative improvements in national wellbeing”. These include cleaner air, reduced rates of respiratory illness, cleaner water, less harm to biodiversity and of course avoiding catastrophic climate change.

The shift to a clean-energy future will touch every aspect of our economy – every product and service must know its carbon footprint and find ways to achieve neutrality. This means there are myriads of economic opportunities for all sectors. The Government’s recent decision to end offshore oil and gas exploration has created a much-needed signal to investors and businesses alike that the future is going to be low-carbon.

There is no question: the time is now. It is up to us to decide the best way forward. As Lord Ernest Rutherford said, “We don’t have much money, so we have to think”.

Change Afoot Down on the Farm

RACHEL STEWART

Farming in New Zealand has never been put under the transformation pump quite like it is right now. Change is afoot, and is being led by some of the more unusual suspects.

As one of this country’s most ardent critics of farming’s impact on the environment – particularly water – it may surprise many to know that I am heartened by the quiet revolution taking place behind the scenes.

Let’s talk to Landcorp. While the company is owned by the Crown, it operates on the same playing field as all other public and private farming entities. It owns or manages 140 farms throughout the country, and is expected to return a profit to its shareholders.

The rhetoric from CEO Steve Carden has been the finest out of the rural sector since forever. Anyone can spout marvellous platitudes about environmental sustainability, but it’s his actions that have really made me – and others – sit up and take notice.

Establishing an Environmental Reference Group (ERG) in 2015 – designed to advise senior management on environmental activities with absolute independence – was a smart move.

Appointing freshwater ecologist Dr Mike Joy to it was an even smarter move. If nothing else, it’s a good look. As was appointing veterinarian, ecologist, and farm advisor Dr Alison Dewes. Along with Joy, she has been a firm critic of New Zealand’s traditional farming model. To then appoint her as Landcorp’s head of environment, a newly-created position within the state-owned enterprise, was nothing short of genius.

The emphasis on the environment had been signalled for some time. In August 2016 Steve Carden announced that their farms would stop using palm kernel expeller (PKE) as a supplementary feed by the following year. The ERG had been discussing it with the organisation for some time.

The move demonstrated Landcorp recognises that consumers are placing more importance on where their food comes from and how it is produced. Even more than that, it sent a really loud message to both dairy farmers and Fonterra – a purveyor of PKE – that solutions to protect the environment are also commercially sensible.

The other big environmental win for Landcorp came partly from the ERG’s focus on their massive dairy farm conversions near Wairakei, above Lake Taupō. Conversions from forestry to dairy began in the early 2000s. There was a large public outcry about the impacts of the conversions on Lake Taupō.

Wairakei Estate comprises 13 dairy farms with 17,000 cows over 6400 hectares. Originally, it planned to run 43,000 cows on 39 farms by 2021 but the plans have been scaled back.

“We’re acutely aware that we do not want to create any legacy issues for sensitive water catchments in the communities we operate in, anywhere around the country,” Steve Carden said.

So scale it back they did, and they’re now planting about 1000 ha a year of forests on the property instead. In terms of riparian planting, significant setbacks, up to 242 metres in one instance, have created buffer zones between the pastoral land and major waterways. The average setback is 75 metres, which well exceeds the required distance.

This is what I call quietly getting stuff done. And because Landcorp’s an SOE, leading by example environmentally is both smart and strategic. While I’ll never agree with them on every issue – they use irrigation, for example (and that’s a whole ‘nother column) – I applaud their foresight and vision.

Because if New Zealand is to have any real chance of solving the environmental crisis that is modern-day agriculture, we’re going to need farmers and their apologists – DairyNZ, Fonterra, Federated Farmers – to start thinking and, more importantly, acting like Landcorp. Is that possible within a relatively short time frame? Because time’s running out.

Farming’s social licence to operate has been close to expiring for a while now. But further to that, the ongoing and insidious degradation of our soil, our water, and our biodiversity continues to creep along in a manner that is not terribly noticeable on a day-to-day basis, but which is steadily destroying our native flora and fauna.

Cutting back on cow numbers, decreasing fertiliser use, slashing back chemical applications, and planting more trees are all on the table. But when will farming’s leaders openly accept that their industry has to change?

Agriculture is the industry most dependent on a healthy environment and most at risk from the effects of climate change. It generates the majority of our export earnings and has an international reputation not only for quality products, but also for being clean and green – despite the fact that that’s now been proven to be a myth.

It’s also an industry starting to suffer animal welfare issues with increasing intensity. Mycoplasma bovis is just the latest.

It’s a pivotal time down on the Kiwi farm, and if farmers don’t get with the programme soon, I fear for the sector. We’ll know when they start embracing change because they’ll start thinking, talking, and acting like Landcorp.

On this, I am holding my breath.