From mountains to sea, the Tukituki presents economic opportunity, but only if it can be harnessed in an environmentally sound way, as Jess Soutar Barron reports.

For Kiwis, rivers are life-blood. Mauri. They feed our spirit, energise us. They are a place of recreation, a place to play, a vital link in our economic potential. For visitors who have been wooed by the 100% Pure New Zealand promotion, rivers and the recreation opportunities they conjure up, are part of the pull.

In Hawke’s Bay, the Tukituki runs 110km north and east from the Ruahine Ranges where the headwaters start in the same hills as the Manawatu River.

It flows past Waipawa and Waipukurau, into Hastings District, where it runs down Middle Road to Kahuranaki Road and then under Red Bridge, to Black Bridge. It meets the sea just north of Haumoana.

In many ways the Tukituki is our defining river, it is certainly the one that makes it into the photographs.

And what is our picture of a perfect river? Clean, clear, cool fresh water; fish, insects, birdlife. A setting for picnics, swimming, angling, kayaking. Traditionally the backdrop for our idyllic day by the river is pastoral: An orchard, a vineyard, a dairy farm.

Here is where we find ourselves walking a fine line between supporting a vibrant economy, enjoying sustainable recreation opportunities, and protecting nature’s intrinsic values.

The Tukituki is a playground, but it’s also a crucial part of our agricultural and horticultural spine. It is an integral cog in our infrastructure, an economic engine, and pivotal to our sense of place and purpose as a region. We ask a lot of our Tukituki. This creates a number of issues, with many people and interests involved: water allocation being one, runoff from farms and sewage discharge being others – what goes in, what comes out.

Ups and downs of water

Nearly 500 consents permit water to be taken from the Tukituki catchment by property owners, mainly for irrigation. But it’s accepted that too much water has been allocated, placing the river ecosystem and recreational values under stress. Certainly in high summer the low flow is too low. But rights are rights and resource consents are resource consents. Clawing back allocation is seen as tricky to navigate – who gets water and who misses out?

The journey to resolution begins close to where the Tuki’s own journey starts, in the Ruataniwha plains. Here, Hawke’s Bay Regional Council is proposing the construction of a $200 million dam and distribution scheme, which will ultimately require $300 million or more when on-farm costs are included.

What farmers want is security of water supply … already an issue, and one that will worsen as global warming begins to take its bite. So to farmers, the ‘promise’ of the dam is increased and more reliable water supply. HBRC’s aim is that consent holders will be migrated to stored dam water for their irrigation, leaving the Tukituki to flow its merry way un-tapped. HBRC talks of a 30% increase in flow. There is even a vague hope that the river might return to “close to normal flows” (Draft Long Term Plan 2012-2022).

However, the dam will also enable up to 30,000 hectares of additional irrigated land, that is, thousands more hectares of intensified farming. Depending on the mix of land use – how many sheep, cows, apples, grapes, potatoes, dairy – this will cause even more nitrates and phosphates to enter the water. The trickle-down effect, pun intended, is that the water in the Tukituki will have even more nutrients in it, harming aquatic life and diminishing recreational values.

But nutrient run-off from farms is not the Tuki’s only problem. Its other major source of pollution is wastewater effluent from two sewage treatment settling ponds, one in Waipawa and one in Waipukurau, which is discharged into the river.

The Environment Court has put new limits on what can be pumped into the river and by 2014 Central Hawke’s Bay must clean up its act. CHB’s first option, pumping half its discharge onto land and the rest into the river, has been opposed by 20 of 23 submitters on the scheme and, for the moment, is tabled. A second option – using worms to eat up offending nutrients – is being reviewed as we write. Whatever option CHB pursues, clearly the clock is running and environmentalists are determined to force compliance with the Environment Court’s more stringent standards.

“The Tukituki is not broken”

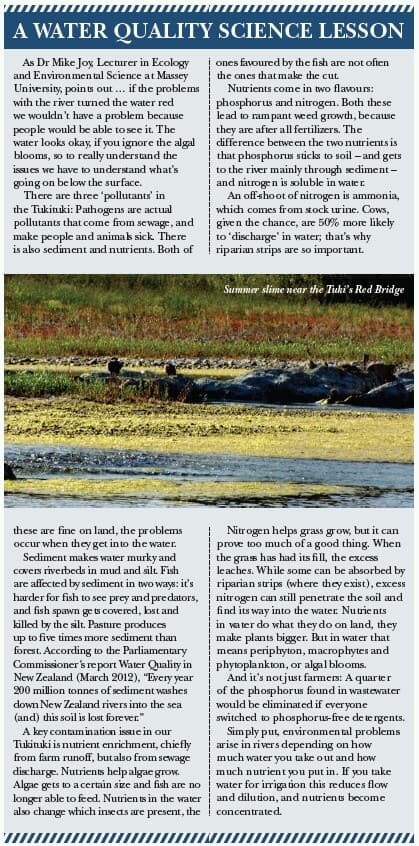

In a recent Ministry for the Environment league table for nutrient levels in New Zealand rivers, the Tukituki fares quite badly. Of 77 rivers, the Tuki is ranked number 51 overall (measured at Red Bridge). For nitrogen it takes 61st place; for phosphorus, 39th; and biological health, 56th.

However, Iain Maxwell (HBRC’s Group Manager of Resource Management, who looks after water quality), believes the Tukituki is not polluted … or at least not seriously so.

“The Tukituki has some need for intervention to manage community expectations, but we’re not at a stage where it’s broken, it’s not.” He does say the Council is putting a lot of effort into nutrient levels and what sensitive species can cope with.

Maxwell stresses Council has a classic balancing act to maintain between community expectation and management of the river.

“As a nation we need to earn our way in the world. It’s a balance to get the mix right. However, we cannot go back to an unmodified environment, we live in a modified environment. But it’s about enabling communities; giving them tools and resources to earn a living, as well as go for a swim or a fish.”

Maxwell, as a keen fly fisherman, understands the importance of fish to the Tukituki, and to those who enjoy getting out into the river.

He warns against something called ‘Prestige Bias’, slanting statistics around fish stocks, size, condition and numbers.

“Anglers will always remember the biggest fish caught on their very best day. It’s fair to say that the trout fishery has changed, but nobody could confidently say how it’s changed. With any fishery there’s a bell curve, fish do respond to some additional nutrients in a positive way. Some nutrient is not entirely a negative thing.”

Fish and Game’s Regional Manager Pete McIntosh sees the quality and quantity of fish in the river is about much more than simply anglers’ braggadocio.

“The Tukituki is a pretty unhealthy river at the moment,” says McIntosh. “Phosphorus feeds algae, most noticeably periphyton biomass, and that changes the insects in the river, and then the fish don’t grow as numerous or as big.”

But are the trout happy?

For McIntosh, trout are the key indicator for water quality. If the trout are happy then the water is healthy. That means a good environment for the complete habitat and ecosystem, including native fish, migrating eels, glaxids and insects, as well as birds like dotterels and stilts, all of which feed on invertebrates.

“If you’ve got it right for trout you’ve got it right for all,” he says.

McIntosh is also concerned about the dam project and where it lies in terms of the river. He explains that the HBRC did look at sites in gullies (two at that stage) but now have moved to an in-stream dam. This itself can have catastrophic effects on fish and eels, some of which use these ancient river paths for spawning, returning to their own place of birth to lay their eggs.

David Renoulf of the Hawke’s Bay Environment Water Group has been fishing the Tukituki since he was a child and agrees with Fish and Game that trout are a gauge to the wellbeing of the water. He challenges the Council’s monitoring methods and believes the single most important factor in improving the quality of the Tukituki is to stop farmers putting too much nutrient on land in the first place.

John Scott has been fishing for over 60 years, and in the Tukituki since 1970. He is concerned that the proposed dam may add to the issues with the river before it rectifies anything.

“The philosophy behind water storage is a good one but what happens when people use that water? There may be extra water in the river but it’s contaminated – so what’s the good of that? I do not support water storage on its own. It’s got to work with the biodiversity of the river. The environment can’t be an after-thought.” Scott says. He also believes that although the HBRC carry out monitoring and testing in the river, this too is flawed.

“The Regional Council isn’t monitoring all the different types of pollutant, they’re very selective. Monitoring needs to happen. But policing? That’s a good question,” he says.

“The Regional Council set minimum flows but they can’t police them, and when the flow in the river gets low there’s no power in the river to flush out pollutants.”

For Scott there are a number of issues with the Tuki that need correcting before any ‘solutions’ are committed to.

Scott has formed Friends of the Tukituki, a group to highlight issues with the river and tackle them at a Regional Council level. He also sits on the Hawke’s Bay Environment Water Group and is a member of both the Hastings and Napier Anglers’ Clubs. He is an environmentalist, a fisher and also understands the ins and outs of local government, having worked alongside councils on many projects over the years. He believes river users need to become much more switched on to what’s happening in the Tukituki.

“If you don’t look after it, you’ll lose it. Every person in Hawke’s Bay pays Regional Council rates – we all have a voice and we can use it. We’ve got to pick up ownership of the Tukituki. If we don’t, people with money will pick it up and steal it. When you get to my age, you can see things unfolding and with the Tukituki there’s a real risk that it’ll get worse. I live in hope, but I am sceptical.”

Pete McIntosh is very clear on what he wants for the future of the Tukituki: “A river that is swimmable, fishable and safe for food gathering. What we want is higher flows of better quality water – if you can get that you’ve solved it all.”

He adds: “Fish and Game is not against economic development, but it needs to be sustainable. We support a growing economy for the region, but only when it’s achieved and promoted within an environmentally sustainable framework.”

Irrigation impacts

Andrew Newman, CEO of the Hawke’s Bay Regional Council, is also mindful of the careful balance the river demands.

“Irrigation impacts on the flows are an important element of the conversation, particularly in those intense times of the year when really everyone wants access to the river for recreational fishing, swimming, aesthetics, as well as for the agricultural production further up in the catchment,” says Newman.

The HBRC readily admits that taking water from the Tukituki to irrigate exacerbates issues with the river, but sees the dam and water storage as potentially a win/win situation: more (and more secure) water for farmers, together with higher flows supporting a healthier river.

But more irrigated land will put more nutrients and sediment into the river. The nutrient loads will depend on how the land is used. However, it is almost impossible to project how land use will change when more irrigation is feasible.

More dairying, for example? One HBRC projection anticipates that one-third of CHB’s irrigated land would go into dairying. Dairying uses huge amounts of water and discharges equally significant amounts of waste. It needs careful, sustainable and concerted management of stock and pasture. And although no one in the debate wants to finger point: In every industry there are cowboys.

There is a fundamental presumption amongst HBRC planners and consultants that there’s significant room for improvement in farming practices that would mitigate the environmental impacts of intensified farming. Obviously, if everyone was already doing the right thing and the river’s already stressed, then there wouldn’t be headroom to accommodate even more farming on the irrigated land.

Farmers and farm scientists know about ‘best practices’ and interventions that can reduce farm pollution. Laundry lists of potential improvements are being prepared as the HBRC readies its case for the dam. But the trick is getting them adopted by the 200 or so farmers who would be served by the dam.

Helen Codlin is HBRC’s Group Manager Strategic Development and the person charged with planning how those who would have consents to take from the river might be required to meet environmental standards (which presently do not exist), how they will be monitored and then held to account.

“To date we have used non-regulatory approaches and what we’ve done in the past hasn’t worked,” says Codlin, who admits that the only people the HBRC has worked with on their resource management practices are those farmers who wanted to be worked with.

Andrew Newman agrees there’s a lot riding on the cooperation of the farming community. “There’s a significant change process for them with this particular journey, but our conversations so far have been open and pretty constructive.”

“We want to return the river to its natural state during those periods of the year when it’s in very heavy use,” he says. “We want to deliver three things: Environmental gains, economic gains, and community resilience. We are also saying that we will bring a variety of interventions into play with which to do that. Some of those are practice based, some of those are regulatory based and some of those are infrastructure based.”

A question that hangs in the minds of many is: If there are rules for farmers upriver participating directly in the dam scheme, will those same restrictions apply to farmers downstream? And, how will farmers take to potentially draconian interventions around what they can or can’t do on their land – for example, limiting cows per hectare or fertiliser inputs?

HBRC claims there are a number of tools in their arsenal in terms of controlling what goes into the river and what is taken out for irrigation purposes. The main concept on the table involves two levels of protection.

First, as required by the new National Policy Statement on Freshwater Management, overall nutrient limits would be set for the first time via the Resource Management Plan for the Tukituki (probably on various segments of the river). Then, based on that framework, farmers’ individual consents to take water – in the form of contracts with the new water company that will own the water storage scheme – would include conditions setting forth required practices.

Of course, environmentalists will be concerned about the stringency of the overall water quality standards, about how protective the conditions placed on individual farmers are, and finally, about how – and how rigorously – they will be enforced.

“Audited self-management should be the way of the future and we have to build that confidence and that trust to get there,” says Newman. “Verification of a system as opposed to compliance of a specific, that’s where I’d like to see the whole regulatory system evolve to.”

“It’s not going to be simple and it will be horses for courses,” says Newman. But HBRC still hasn’t said exactly what the limits will be, how ‘prescriptive’ the conditions placed on water use will be, or what form penalties for breaches will take. Said one HBRC staffer: In Australia, they turn the water off.

Graeme Hansen, HBRC’s Group Manager Water Initiatives, is the project lead on the dam proposal. He’s philosophical about change in the behaviour of farmers.

“We’ve gone from the good old days where we didn’t know what we didn’t know, and farmers were saying let’s just pour it on, it doesn’t matter – be it water or fertiliser. I think there’s a real awakening in this world and in this region.”

What next?

To summarise the issues:

- Will stringent minimum flow and water quality standards be set, and if so, how will they be enforced?

- Will farmers enjoying ample water as a result of the water storage scheme be required to do their bit for the good of the river … or merely encouraged?

- Will CHB deal effectively with its sewage discharge into the Tukituki?

It’s a lot to absorb, and not a lot of time to do it in. The water storage scheme is floated in HBRC’s Long Term Plan, which must be adopted by June 30. Yet key decisions about water quality standards, allocation mechanisms, and mitigation practices and enforcement are yet to be made.

In fact, the key land use and environmental studies have not been completed and released to the public.

Yet the public’s opportunity to comment on the dam proposal will end on May 16. It seems the Regional Council has put the cart before the horse … perhaps leaving its process open to challenge.

Our picture perfect river setting might appear all right on the surface, but swim a little deeper and the future wellbeing of our wairua may not be so clear.