[As published in May/June BayBuzz magazine.]

“everything, everywhere, all at once”

With so many developments to absorb on the climate change front, it’s perhaps best to start with the big picture and work our way back to how New Zealand and Hawke’s Bay presently fit in.

Global scene

In the last few months, international debate has been driven by the ‘Synthesis Report’ issued by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in March. In 37 pages it summarises the 10,000 pages of research the IPCC has released over the past five years. It sets the stage for COP 28 at year’s end.

Said UN Secretary Antonio Guterres: “Humanity is on thin ice – and that ice is melting fast … This report is a clarion call to massively fast-track climate efforts by every country and every sector and on every timeframe. In short, our world needs climate action on all fronts – everything, everywhere, all at once.”

The IPCC report observes:

• “Global GHG emissions in 2030 implied by nationally determined contributions (NDCs) announced by October 2021 make it likely that warming will exceed 1.5°C during the 21st century and make it harder to limit warming below 2°C. There are gaps between projected emissions from implemented policies and those from NDCs, and finance flows fall short of the levels needed to meet climate goals across all sectors and regions.”

• “Limiting human-caused global warming requires net zero CO2 emissions.”

• “If warming exceeds a specified level such as 1.5°C, it could gradually be reduced again by achieving and sustaining net negative global CO2 emissions. This would require additional deployment of carbon dioxide removal, compared to pathways without overshoot, leading to greater feasibility and sustainability concerns. Overshoot entails adverse impacts, some irreversible, and additional risks for human and natural systems, all growing with the magnitude and duration of overshoot.”

• The report emphasises that nations must address both mitigation (actual reduction of GHG emissions) and adaptation, noting: “Delayed mitigation and adaptation action would lock-in high-emissions infrastructure, raise risks of stranded assets and cost-escalation, reduce feasibility, and increase losses and damages.” Without mitigation, adaptation options will become increasingly constrained and less effective.

“The choices and actions implemented in this decade will have impacts now and for thousands of years.”

• “The choices and actions implemented in this decade will have impacts now and for thousands of years.”

In short, the panel says the world must cut GHG emissions to 60% below 2019 levels by 2035 (and emissions must peak before 2025 for a 50% chance to hit 1.5C with little or no overshoot) – or we’re screwed … and collectively nations are nowhere close to doing that.

Authors do emphasise that the technical know-how is available to meet the challenge. Even Guterres calls the report “a how-to guide to defuse the climate time-bomb”. What is lacking is political will.

Under the Paris Agreement, nations were required to submit commitments (Nationally determined contributions – NDCs) regarding the GHG emissions reductions they would make by 2050. The next round of NDCs must be made in 2025, and nations will begin to formulate fresh commitments as the next global climate conference (COP27) occurs this December.

Guterres wants developed countries to reach net zero by 2040, not 2050. He calls for no new coal plants by 2030, an end to burning coal in rich countries that same year and all countries by 2040, and ceasing all licensing and funding of new oil and gas.

In the meantime, China has approved more coal projects than all other nations combined in 2022, while the US proposes new oil drilling in Alaska.

New Zealand lags

So how is New Zealand faring?

Since 1990, the base year for all nations reporting to the UN, New Zealand’s gross emissions have increased by 19% and net emissions by 25%. Only the waste sector’s emissions have decreased (by 18%) since 1990, as we have got better at managing solid waste at municipal landfills. NZ has had the second-highest increase in net emissions since 1990 of industrialised nations, behind Turkey. We rank fifth in the OECD for total emissions per capita.

During the 2017 election campaign, Jacinda Ardern asserted: “We will take climate change seriously. This is my generation’s nuclear free moment.”

Newsroom senior reporter Marc Daalder counters: “I don’t think that the action we’ve seen from the Government over the past two terms, or over any term of Parliament ever, has been consistent with Jacinda Ardern’s proclamation.”

Our Climate Commission has been quite grumpy that its recommendations for tougher emissions policies have not been accepted by the Government.

However, NZ does now have the Zero Carbon Act and the Climate Change Commission, as well as its first Emissions Reduction Plan, a roadmap for emissions reductions over the next 15 years (arguably sufficient to meet NZ’s current NDC commitment under the Paris Agreement). And we’re a world leader in renewable energy – only Norway and Brazil generate a higher share of renewable energy.

We aim to be carbon neutral by 2050, with biogenic methane emissions at 24-47% below 2017 levels. All farms were to have measured their GHG emissions by the end of 2022 and have mitigation plans in place by 2025.

Some good news from the Ministry for the Environment is that NZ gross GHG emissions in 2021 were down 0.7% from 2020, after a 3% decrease in gross emissions in 2020 compared to 2019.

With the country’s transport fleet responsible for 39% of total domestic CO2 emissions, the rapid uptake of electric vehicles is a positive trend. Our car fleet is one of the dirtiest in the OECD. About 20% of the 100,000 light vehicles sold in New Zealand last year were battery electric. There are more than 69,000 EVs – plug-in and full-electric – on the roads, a more than 80% jump compared with the end of 2021.

A new national EV charging strategy recently announced by Transport Minister Michael Wood aims to provide charging hubs every 150-200 kilometres on main highways, a public charger for every 20-40 EVs in urban areas, and public charging at community facilities for all settlements with 2,000 or more people. This would see tens of thousands more EV chargers across the country.

The Government also plans to revise consenting rules related to wind and solar installations, after a March Infrastructure Commission report said that NZ needed to dramatically speed up the consenting process for new power projects to have any chance of meeting its 2050 GHG emissions targets.

Announcing the planned rules, Environment Minister David Parker said: “We are not saying that everything should be consented, but it needs to be easier than it is now.” The new rules provide for fast tracking wind/solar consent applications and address issues like ‘amenities’, where ‘outstanding landscape’ concerns have prevented the development of wind farms in particular. The discussion document says: “[It would] enable renewable electricity generation activities in other areas, including where there are potential adverse effects on local amenity values, so long as effects are avoided, remedied or mitigated to the extent practicable.” Parker says the need for renewable energy must be recognised and every region needs to do its bit.

Alongside a promising trend with respect to EVs, we’ve had declining coal use, with less coal burned in the last quarter of 2022 than any quarter since 1990.

However, the Government is yet to finalise terms with respect to pricing agricultural emissions, our biggest problem. A levy structure for farm emissions was outlined late last year, and a pricing system must be in place by 2025, but details are yet to follow. Until this is resolved, it’s impossible to envision how NZ meets the aspirations of the UN and, more critically, the needs of the planet.

Will we toughen up on climate action?

It wasn’t a good sign when the Cabinet dismissed the recommendations of the Climate Commission and Climate Minister James Shaw late last year and suppressed the possible price of carbon in NZ’s Emissions Trading Scheme. A higher price range, as recommended, would have incentivised decarbonisation.

Commission Chair Rod Carr wrote to Newsroom: “… If the Government chooses to constrain price discovery, the NZ ETS will play a weaker role and the Government – now and in the future – is more likely to need to adjust the emissions reduction plan to include further regulations and other policies to drive emissions reductions and ensure budgets will be met.”

And if we do not actually reduce emissions more aggressively, NZ will need to try to buy its way to net zero by purchasing offsetting overseas carbon credits, at a cost that could hit $24 billion, according to a Government report in April.

With a slowed and inflationary economy, politicians as a breed are loath to support initiatives that involve near-term costs with long-term benefits. And the NZ consumers who elect them seem to be no different. The percentage of Kiwis committed to “living a sustainable lifestyle” has dropped from a 13-year high of 43% in Kantar’s 2022 report to 32% in this year’s survey, Better Futures 2023. Climate change does not rank amongst the top ten concerns of New Zealanders (although extreme weather events ranks eighth).

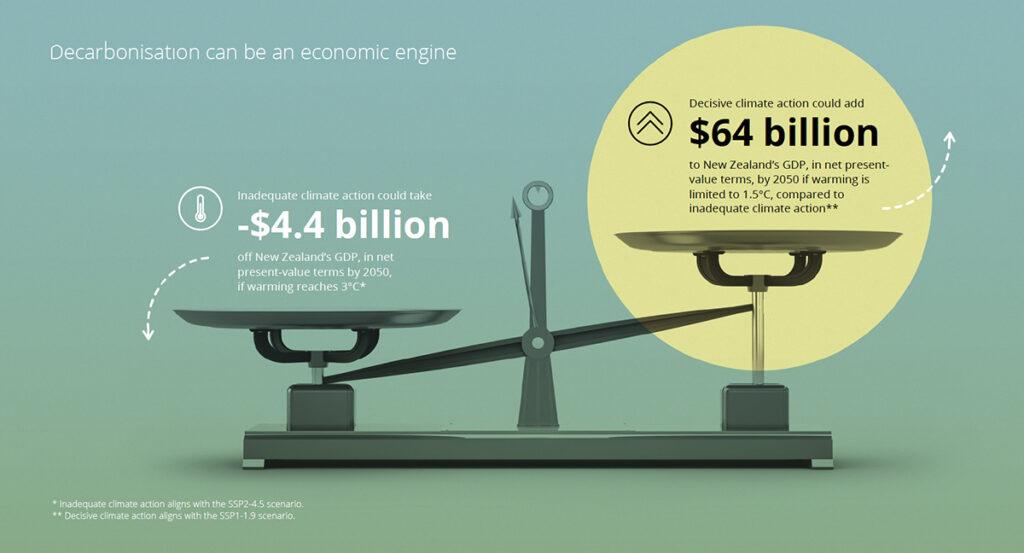

Choosing a more aggressive path to reducing NZ emissions is confronted by that reality. Yet the cost of not tackling GHG emission aggressively is daunting. A March report by Deloitte – Asia-Pacific’s Turning Point – says that a business-as-usual approach will actually reduce GDPs.

Looking at New Zealand, Deloitte says: “This report challenges the assumption there is an additional cost burden to decarbonising New Zealand’s economy over the next decade, by showing the direct connection between decisive climate action and future economic prosperity.”

The report estimates a $4.4 billion loss in NZ’s GDP from ‘inadequate’ climate action by 2050 (escalating to $48 billion by 2070) versus a $64 billion gain from ‘decisive’ action (i.e., action that kept temperature rise to 1.5C). The ‘turning point’ for NZ where the benefits of rapid decarbonisation outweigh the costs could occur around 2036 says Deloitte.

Says Deloitte: “Under ‘decisive action’, New Zealand’s greenhouse gas emissions reduce by 75% in total by 2050 compared to 2022.” Efforts required include “incentivising investment in decarbonisation in key areas to reduce biogenic methane, set up new markets and infrastructure for renewable energy (e.g., hydrogen), and meet the needs of an increasingly electric fleet (e.g., transmission and rapid charge infrastructure).” Currently we are committed internationally to emissions reduction of 30% below 2005 levels by 2030.

Of special importance to NZ’s export-driven economy, Deloitte warns: “If no change is made and New Zealand falls behind, key exports could be impacted as trading partners commit to net zero targets and start to focus on the sustainability of their imports.” As then-PM Ardern noted last year in previewing the Government’s agricultural emissions approach: “With or without the Government’s proposals the world is changing and New Zealand needs to be at the front of the queue to stay competitive in a market that is increasingly demanding sustainably produced products.

“Tesco, the biggest buyer of New Zealand products in Britain, wants all their products to be environmentally accredited and reach net zero across their entire supply chain by 2050.”

Heaps of economic analyses echo the proposition that the economic benefits of renewable and circular energy products and services (and avoidance of damaging effects) will surpass the losses associated with clinging to carbon.

Is HB hot about climate change?

Not really.

We have a Climate Ambassador, Pippa McKelvie-Sebileau, at the Regional Council. In response to Cyclone Gabrielle, she recently wrote: “But more than ever, we must ask how we can slow this thing down. We’re in a leaky boat and we can’t just keep bailing out the water; we have to try and close up the leaky hole. Slow down the catastrophic events.”

The rhetoric seems more urgent than the action.

Our territorial authorities have appointed staff leads for marshaling climate action in their jurisdictions, having been handed profiles of each jurisdiction’s GHG emissions. And a working group convened by HBRC including these folks and a small number of outside voices are supposed to be developing a regional Emissions Reduction Plan.

Apparently that plan will include: Waste, Working with Nature, Transport, Emissions efficiencies in the rebuild. Will the plan have some real grunt, or will we simply be urged to recycle, cycle for recreation and scooter around Napier more?

HBRC is working on a Climate Change Risk Explorer, a spatial-based risk assessment tool that layers hazards, assets and other information under different climate scenarios, potentially of use in informing recovery plans.

The working group has no primary sector representation. Addressing the region’s agricultural emissions seems to be in the ‘too hard’ basket. Precisely at a time when re-thinking the ‘how, where and what’ of our region’s agricultural economy should be a top priority.

Fortunately, the gap in council leadership has not stopped businesses like Napier Port, HB Airport, Pan Pac, Silver Fern Farms, WineWorks and others – from progressing major sustainability programmes that include reducing their carbon footprints. BayBuzz has been reporting on these initiatives online.

Climate work has undoubtedly been slowed by cyclone emergency demands on council staffs. But perhaps of greater worry is the public’s apathy and competing worries, like inflation.

This warning is raised by the Kantar survey, which observes in its conclusions: “Perhaps the issue of greatest surprise is the 24-39% of those who were affected by Cyclone Gabrielle who still do not rate Extreme Weather as an issue of concern.”

Reports and economic analyses from the UN and the likes of Deloitte and virtually every global food producer/marketer are not at the top of most consumers’ reading lists.

But if this cyclone event in our own back yard hasn’t served as a blaring alarm that we cannot proceed business-as-usual, it’s hard to imagine what might spur more urgent action in all sectors, by all players, to both mitigate and adapt to global warming.

As UN Secretary Antonio Guterres pleads: “… our world needs climate action on all fronts – everything, everywhere, all at once.” If you read nothing else about what must be done.

Read his full remarks here accompanying the Synthesis Report.

Firstly we need to change the language we use around these issues. EVs are not “more sustainable” or “environmentally friendly”. They are “slightly less environmentally damaging”. When framed that way it makes it clear that they are not the answer. They reduce tailpipe emissions at the point of use, but can be more damaging during manufacture.

And the idea that 43% of kiwis are living a “sustainable lifestyle” is laughable. With 8 billion of us on the planet a truly sustainable lifestyle would be something like life was in the early 1800s.

I am all for becoming more environmentally friendly. There is a lot that could be done individually, but all of us driving EVs won’t do it. We have mandated double glazing, for example. What about mandating solar systems on all [almost] new builds? Oh, the cost/benefit analysis does’t work. Well, explain to me how the cost benefit of an elaborate kitchen, with marble countertops etc etc works.

Explain to me, too, how all the effort and cost of reducing carbon emissions locally will help change our climate when NZ’s contribution to the total world emissions is only about 0.17%.

Be careful that we don’t destroy our economy in the process, because our climate in NZ cannot change unless the whole world changes.

You are right Brian, us reducing our emissions will make diddly squat difference to the global climate, however, fossil fuels are finite so reducing our reliance on them will increase our resilience as they start to become less available (which may be quite soon…). The economy is ultimately energy based and renewables cannot replace the ~80% that is currently fossil fuel derived. Tom Murphy does an excellent job of exaplaining why here https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9js5291m Humans are headed for a simpler way of life in the not too distant future

Glen, thanks for the reference. That is probably the best book on the subject that I have seen. It ought to be compulsory reading for all politicians, and journalists.

I recall our lecturer in electrical engineering way back in 1960 telling us that the known world sources of oil would be depleted in the 1980s. The operative word of course is “known”.

It won’t be long before we’ll all be subsistence farmers riding bicycles.

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Oil-field-discoveries-and-world-oil-production-history-6_fig6_260266121

The problem is that we found the easy stuff first and are very unlikely to find huge reserves like that again (which would be a disaster for the climate/biosphere anyway). Plus, the energy required to extract oil has been increasing over time so for every barrel we extract now we get less use out of it https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301421513003856

You might be ineterested in this model/website. https://surplusenergyeconomics.wordpress.com/ which describes the disconnect between our “financial” system (which is more and more built on debt) and the energy which underwrites it. It neatly explains why productivity has been stalling in recent decades as the energy cost of energy has risen.