Talk of a national screening programme presents another time bomb, the chronic shortage of specialists, including gastroenterologists and surgeons, the only ones qualified to perform colonoscopies (internal bowel or colon tests).

Department of Health figures for 2012, released in October 2015, show colorectal cancer is the third most prolific cancer (3,016), but more die from it (1,283) than breast and prostrate cancer combined.

This is the highest rate per population in the OECD; only lung cancer produces more fatalities in New Zealand (1,628 deaths).

Despite being given ‘top priority’ and demand exceeding specialist capacity, Health Minister Jonathan Coleman has put a ‘business case’ to Cabinet for a staged screening programme from early 2017, although Bowel Cancer New Zealand suggests nationwide coverage may realistically take until 2020.

Hawke’s Bay general and colorectal surgeon Bernard McEntee and Hawke’s Bay District Health Board (HBDHB) endoscopist Malcolm Arnold have been briefing their peers in preparation for the roll-out after meeting with Minister Coleman.

The template is a $31 million, four-year Waitemata DHB pilot which began in October 2011 and detected “a large number” of ‘adenoma precancerous polyps’ in the target age group. Seventy percent were deemed “amenable to cure” because they were caught in the early stages, says McEntee.

The pilot, now extended for another two years, generated such a huge demand for colonoscopy that keeping up has been challenging. From the 55% response rate, more than 6,000 colonoscopies have been performed.

“There was a 20% increase in symptomatic referrals for endoscopy [rectal tests] and in Hawke’s Bay we’ve already had a few positive results from the lab in Australia after people purchased kits from local pharmacies,” says McEntee.

If those detection statistics were replicated nationwide it would be “a massive saving”. If caught early 75% of bowel cancer is curable, left undetected there’s a high risk of it requiring extensive chemotherapy or becoming untreatable.

There’s no disputing that early detection screening is the most cost-effective way to get to the bottom of the problem before more expensive procedures are required.

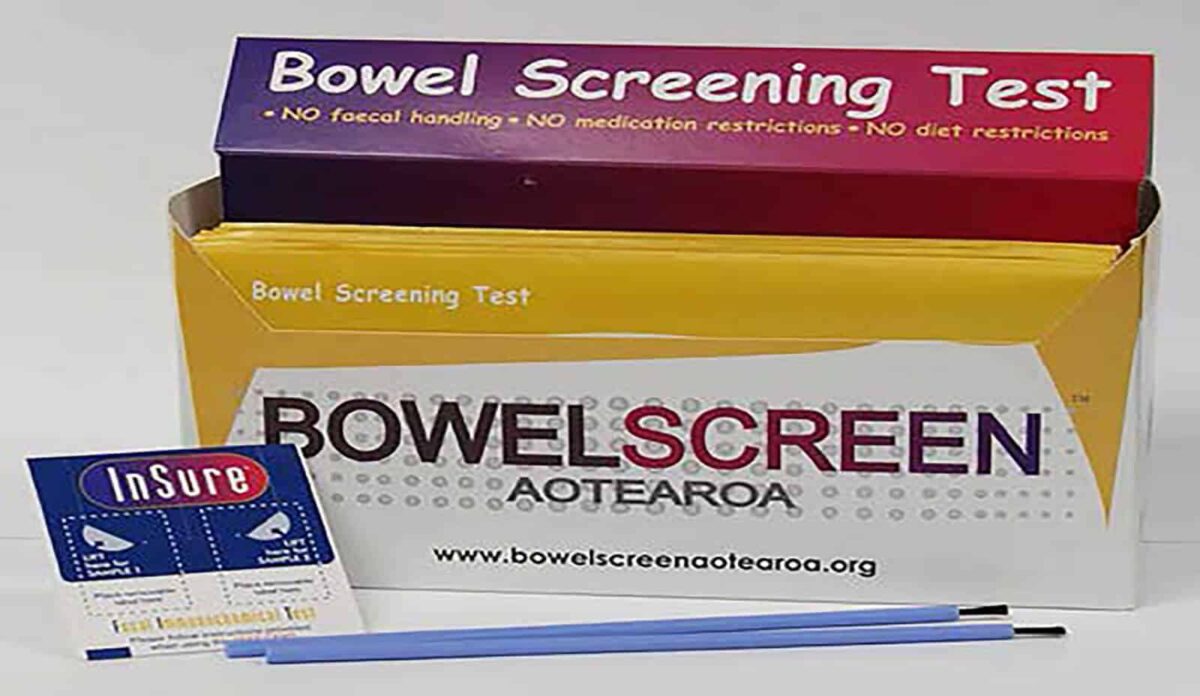

Already though, existing awareness campaigns, including Bowel Cancer Month in June and the demand for self-testing kits ($60-$70 each – “less reliable than those used in Waitemata”), are stretching resources, including in Hawke’s Bay.

Bowel cancer is most prevalent in the 50-74 year age group and looks to be growing at around 20% a year, with increased risk through genetic and ‘environmental’ factors, possibly including high intake of red meat.

While the Government is committed to a national roll-out “in some form”, McEntee says the age bracket may be narrowed and the sensitivity of the haemoglobin tests tightened to produce less positive tests. “While this might miss some cancers, it won’t be a significant number according to the modelling.”

Urgent cases would still be picked up and through a surveillance programme precancerous polyps could be tested every two years “without overloading the system”, eventually “preventing it happening at all”, suggests McEntee.

The trouble is symptoms are non-specific. “Rarely is there pain and only a little bleeding and subtle changes in bowel habits which people can often explain away by their diet or think they’ve got a bug.”

There’s also a degree of social stigma and for some the idea of taking a sample of their own faeces, placing it in a zip lock bag and sending it off to the laboratory for testing is not an appealing prospect.

“Some don’t want to be screened at all knowing they might be faced with a colonoscopy. You’re never going to get everyone to buy into it.”

In 2014 the Ministry of Health agreed a screening programme would have to be carefully staggered, and urged district health boards to prepare for additional demands as too many were already on colonoscopy waiting lists.

A ministerial report that year showed 40,926 colonoscopies were needed in the 2011-12 financial year but 9,397 people missed out because resources weren’t available. The number of colonoscopies has been increasing at an average of 15-20% annually since the 2008-2009 financial year.

There are only 608 medical professionals able to perform the operation across the wider health sector; 109 are gastroenterologists, the rest are general surgeons who have to fit it in with other duties.

It’s been estimated another 100 specialists would be needed for a national screening programme and the additional 30,000 colonoscopies likely. Current planning only allows for 37 over the next decade.

In the 2013 and 2014 Budgets the Government added $11.4 million to help DHBs reduce waiting times for diagnostic tests, including colonoscopies. Just before Christmas an additional $4 million was added for additional colonoscopy services.

The ministry insists everything is being done to address the skills shortage, including training nurses to perform checks and attracting more gastroenterology trainees.

McEntee says even training a nurseendoscopist takes several years. One way of resolving the short-term problem he suggests is to “get some Brits over”. However, Britain is facing its own shortage of specialists.

Currently there’s only one endoscopy suite at Hawke’s Bay Hospital although a new suite with two rooms is scheduled to be completed in 2017. “It’ll then be a matter of who’s going to do the extra endoscopies.”

Based on the Waitemata DHB trial that could mean an extra 15 colonoscopies a week — typically day surgery — and around 30 bowel cancer operations a year, each taking half a day.

Surgeons might be able to cope with the increased volumes but dealing with the pathology and endoscopy may still present problems. “While surgery numbers drop over time you still need a surveillance programme and to keep on top of what is found.”

And says McEntee, polyp testing has to be processed by pathologists who might also be in short supply. “You can’t have histology sitting around too long unread…it needs to run alongside the quality of service to patients and not interfere with that.”

There are national guidelines in place to ensure urgent cases are triaged within two weeks and others within six or 12 weeks depending on indications.

Around 60% now receive a colonoscopy within the six-week targeted time compared to less than a third in 2014, although waiting times for non-urgent and surveillance colonoscopies are still slightly below target.

GPs can also fail to pick up the signs and there’s variability in how different health boards meet triage guidelines. “We do what we can in Hawke’s Bay and it can at times feel like you’re not doing the best for the patient, but you have to be as fair as possible.”

McEntee says accurate and more detailed information leads to quicker treatment, a quality referral with blood tests can make all the difference, and he urges doctors with colonoscopy patients who haven’t been seen in a timely fashion to “stay on the case”.