[Editor: This article first published in Jul/Aug BayBuzz mag.]

After what has seemed like an endless procession of target-setting, establishing a Climate Change Commission, interim reports, nation-wide consultations, draft discussion documents and more targets, it seems that New Zealand – or at least our current Government – is (almost) ‘ready to roll’ on mitigating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and adapting to climate change.

And Hawke’s Bay is snapping to attention as well.

The Government’s official Emissions Reduction Plan (ERP) for the next three-year window has been released, with $4.5 billion raised by the Emissions Trading Scheme earmarked for climate-related programmes. I note ‘almost’ ready because the Government still must make its final decisions regarding agricultural emissions, the elephant in NZ’s GHG room. More on that in a moment.

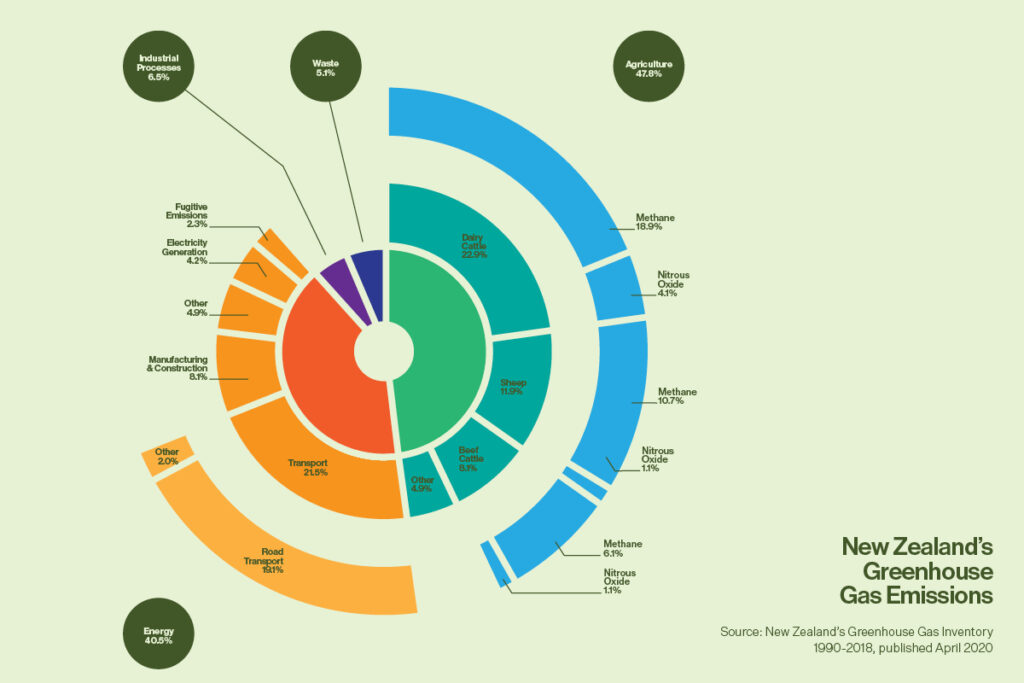

See the diagram below for our current profile.

The ambitiousness or intensity of NZ’s GHG reduction effort is driven by the degree to which our Government in power and citizens perceive and support a need for our country to ‘do its part’, or even provide leadership, as a global citizen in addressing this global existential threat.

On the international stage, countries are expected to declare and meet ‘Nationally Determined Contributions’ to reducing and/or offsetting their carbon emissions.

In any scenario for NZ, we will need to shop aggressively overseas for carbon offsets (e.g., planting trees in Indonesia), given the scale of our agriculture-generated emissions, especially biogenic methane. For these offsets, we will pay $6-14 billion. The alternative is far deeper domestic reductions in GHG emissions at costs to the economy and forced changes in our consumer behaviour that are deemed politically unacceptable.

As a nation, we might respond out of a sense of inter-generational and planetary moral duty, or perhaps more to avoid being ostracized as a political and trading partner by countries committed to heavier lifting.

The latest UN projections in April paint a dire picture, said the report.

Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of climate change

“… limiting warming to around 1.5°C (2.7°F) requires global greenhouse gas emissions to peak before 2025 at the latest, and be reduced by 43% by 2030; at the same time, methane would also need to be reduced by about a third. Even if we do this, it is almost inevitable that we will temporarily exceed this temperature threshold but could return to below it by the end of the century. “It’s now or never, if we want to limit global warming to 1.5°C (2.7°F),” said Jim Skea, co-chair of the IPCC Working Group for this report. “Without immediate and deep emissions reductions across all sectors, it will be impossible.”

Will NZ do its part? No, according to our Climate Change Commission.

The Commission finds that the Government’s commitment (under the Paris Agreement, the current global benchmark) to reduce net emissions by an average of 30% from 2005 emissions levels over the 2021-2030 period is not compatible with global efforts to limit global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.

The Commission observes: “If Aotearoa is to play its part as a developed nation, the NDC (Nationally Determined Contribution) would need to be strengthened to reflect emission reductions of much more than 35% below 2005 levels by 2030.”

Such increased reductions would go beyond the pathways the Commission has recommended for NZ at present. And so the Commission kicks this to touch: “We consider that these judgements, and the decision on the level of international commitment, should be made by the elected government of the day.”

Which returns us to the Government’s ERG, which most environmentalists argue falls short of the urgent action required.

However, the focus of this article is not the ‘macro’ situation, but rather on the changes that announced or likely Government policies might have on our activities right here in Hawke’s Bay. And what we can do here to confront the issue.

At first blush, this brings us directly to that elephant – on-farm emissions.

Our local profile

Hawke’s Bay, which at 3.1 kilotonnes of CO2e accounts for only 4% of NZ’s total GHG emissions, can take some satisfaction over reducing our regional emissions by 7.1% over the 2007-2018 (latest official stats available).

For now, our best regional snapshot of Hawke’s Bay’s GHG profile is derived by extrapolating from national statistics. If the nation’s total dairy herd emits X tonnes of methane, then HB’s herd must emit its proportionate share. The same with auto emissions, etc.

On that basis, in Hawke’s Bay, agriculture accounted for 65.5% of our GHG emissions, while methane accounted for 61.9% of our total emissions. As a region driven by primary production, not surprisingly it’s livestock generating the biggest portion of our emissions.

The policy settings that will dictate the emissions reduction behaviour of HB farmers and growers is outside regional control. By law, all farming operations in NZ must have measured their GHG emissions by the end of this year, and have mitigation plans in place by 2025. There is cross-party agreement on methane targets – as mandated by the Zero Carbon Act, biogenic methane emissions from agriculture (and waste) are to be 10% lower by 2030 and 24-47% lower by 2050 (compared to 2017 levels).

NZ is also signatory to the Global Methane Pledge coming out of the UN Climate Conference last November in Scotland. Signatories to the Pledge are committed to a collective goal of reducing global methane emissions by at least 30% from 2020 levels by 2030.

By the end of this year, one way or the other the Government will set a price on farming-related emissions, perhaps accepting the recommendations of a sector-wide proposal coming out of the primary sector’s He Waka Eke Noa (HWEN) consultation and negotiating process. HWEN accepts that there will be farm-level GHG pricing, with levies beginning in 2025. The new elephant in the room is pricing.

That price will determine how strongly farmers and growers are ‘incentivised’ to reduce their emissions and how quickly. Importantly, the price cannot be set without an eye to global economics. The latest World Bank analysis of national carbon taxes and carbon trading offsets finds that less than 4% of global emissions are currently covered by a direct carbon price in the range needed by 2030 to meet the temperature goal of the Paris Agreement. The Bank says NZ’s prices might need to double.

Our region’s farmers and growers will decide how they can best reduce or offset their GHG emissions. And we do have some ability here in the region to shape what those responses might look like.

HWEN anticipates that there would be an ‘approved’ list of emission-reducing changes (e.g. genetics, feeds, technology) that if adopted would qualify for financial relief.

But not yet included are so-called ‘regenerative’ farming practices, which have demonstrated the ability to build and store carbon in the soil. Here in Hawke’s Bay, a project supported by the HB Future Farming Trust has established that regen practices have increased soil carbon significantly. To further build the evidence base, the Trust plans to replicate this measuring and monitoring regime across a number of ‘paired’ pastoral farms (conventional vs regen) across HB.

This is not a minor matter. Sequestering carbon in the soil could prove to be more economically and environmentally rewarding than planting plantation pine forests, a path most farmers are keen to avoid.

Referring to the significantly more soil carbon (64 tonne/ha) in the HB regen dairy farm studied, soil scientist Paul Smith notes: “To put this into perspective, it converts to 235 tonnes of CO2-e, or roughly the same as a pine forest would accumulate in 8 years. If we can show, with more measurements over time, that these sorts of changes are due to the farming methods employed then the industry can start to incorporate some of these methods into best practice and begin to recognise gains as GHG offsets.” And that is indeed the long-term goal of Beef + Lamb NZ.

Moreover, carbon-rich soils retain much more water, a not incidental co-benefit!

Our region’s expected impacts from global warming reach well beyond pastoral farming. NZ’s first National Climate Risk Assessment observed:

“The primary sector faces risks from extreme events and ongoing, gradual changes. Climate change will reduce the quality and quantity of output across many areas including horticulture, viticulture, agriculture and forestry. Changes in temperature and seasonality influence maturation, length of growing season and the quality (size, shape, taste) of horticulture products; the distribution of pests and diseases and the efficacy of some pest control agents.

The assessment noted that Māori economy would be especially impacted, given its focus on primary production industries.

But while climate change and on-farm GHG emissions are becoming a really big deal to HB’s farmers and growers, and will reshape what the region produces and how, what about the majority of HB residents … townies who don’t get much dirt under their fingernails? What does GHG reduction mean to them?

So, what are we doing?

Starting with local government …

Ironically, the region’s biggest current investment in responding to climate change relates to flood control – global warming will result in more severe and more frequent weather events.

In August 2020, the Government announced $19.2 million in ‘climate resilience’ funding coming to Hawke’s Bay for four flood protection programmes, including Heretaunga Plains (where 80% of the population lives); Wairoa River Scheme (Ferry Road); and two stretches of the Upper Tukituki.

And in terms of planning attention, the coastal protection strategy, focused on our coastline from Westshore to Clifton, has identified protection measures ranging from ‘hard engineering’ to ‘managed’ or ‘planned’ retreat. This planning process, now in HBRC’s hands to implement, is rated most advanced in NZ. Hundreds of millions in protective measures will be on the table over the next 50 years.

Both of these initiatives fall into the ‘adaptation’ column. But that’s hardly all – or even the most critical – we must do. Where the rubber meets the road is ‘mitigation’ – actually reducing our GHG emissions.

The Regional Council has set a goal for the region – achieving net zero emissions by 2050. HBRC completed the first assessment of its own corporate emissions in December 2020, and now publicly reports on these regularly. None of our territorial councils yet do this although there are noises about this happening for NCC and HDC.

HBRC has named a Climate Ambassador, who has begun to assemble benchmark data and an ‘Action Network’ of fellow organisational travellers, and NCC a Climate Resilience officer. A similar role appears in the cards for HDC as it begins to implement its ‘Eco-District’ Strategy.

From the starting point of knowing their own ‘corporate’ carbon footprint, based on work being undertaken by HBRC, by year’s end each of HB’s four ‘territories’ will have their own carbon footprint estimates, built from the bottom up, looking at what emission-producing activities actually occur in each jurisdiction.

Back to the adage: You can’t change what you don’t measure.

And this will enable a focus on what local businesses and major enterprises (like the hospital, EIT and our schools) are doing to reduce their carbon footprint. And what you and I should do as consumers.

I suspect many of us would be surprised at the extent of business leadership in the region on this front. Here are a few examples.

Napier Port is committed to net zero emission by 2050 and has an extensive sustainability programme to back that up.

Hawke’s Bay Airport trumps the Port, committing to net zero by 2030. Ours is the first regional airport in NZ to achieve an international standard – Airport Carbon Accreditation Level 2. A key aspect of the Airport’s strategy is construction of a 24.2 megawatt solar array on its site, capable of powering the airport and more.

Given the importance of meat production to the region, the plans of Silver Fern Farms are especially noteworthy. SFF was the first red meat company in NZ to adopt a sustainability programme, verify its carbon footprint and set an emission reduction target — total GHG emissions this year were 13% lower than last year and 20% lower than three years ago. Their target: 30% reduction on 2005 levels of the GHG emissions intensity of operations per tonne of product before 2030; and 10% reduction of energy use per kg of product produced. So far energy use is down 7.7%. And since 2017, 6% less fossil fuel used per kilogram of product.

Hence the PM pitches SFF’s ‘Zero carbon Angus beef’ to Americans via Stephen Colbert’s ‘Late Show’.

Then there’s another HB product, wine. Most of it is bottled by Hastings-based WineWorks. Last December founder Tim Nowell-Usticke told BayBuzz: “We committed to Carbon Zero a year ago, and this is in response to the whole wine industry recognising that sustainability is seen as a very important plank in our export customers’ buying decisions.

“So not only does it help us sell our product, but from our team’s perspective it is the right thing to do. We have started with a 30% net reduction per annum, which we are achieving, and a year ago we started investing in carbon credits here in NZ (native plantations) to offset to Carbon Zero.”

I have no doubt other HB companies are stepping up as well (and would love to hear from you). Civic responsibility and smart business go hand in hand. Better use of energy and less waste of all kinds yield better bottom lines both commercially and environmentally.

It would be great to see a bit of healthy competition arise – in full public view, perhaps with a ‘scorecard’ reported by HBRC – as our local companies out do each other saving money and the planet.

That leaves you and me

Two years ago, the Regional Council surveyed residents on their climate change awareness and concerns. When asked, ‘How concerned are you about the impact of climate change in our region?’, 29% replied ‘somewhat concerned’ and 33% ‘very concerned’. An OK starting point, but we need to do better.

Our ‘contribution’ to global warming is as consumers. And chiefly we drive petrol and diesel vehicles, heat the air around our poorly-insulated homes, and generate enormous amounts of waste.

In 2018, transport emissions made up 36.3% of total long-lived gases. The Climate Commission noted that emissions from domestic transport have continued to rise even as emissions from other sectors stabilised or decreased. It said NZ can cut almost all transport emissions by 2050 because the technology already exists and is improving fast.

Commendably the Government has incentivised electric vehicle purchases and will disincentivise gas guzzlers. Conversion to EVs is picking up nicely, but they are still a very small share of the car pool.

The Climate Commission said: “We want to see the majority of the vehicles coming into New Zealand for everyday use electric by 2035.” And recommended that no further internal combustion engine (ICE) light vehicles should be imported after 2032. The Government’s ERP ducked that recommendation.

Meantime six major automakers, accounting for one-quarter of global sales, have announced end-dates to their production of ICE vehicles, and 30 countries have announced phase-out dates. The European Parliament is considering a total ban by 2035 of ICE vehicles.

Whether we like it or not, in a generation or less, we’ll be all-EV.

If you’re not ready or can’t afford to drive electric, you can always drive less! One study by the University of Auckland study estimates if just 5% of all short, vehicle-based urban trips were done by bike it would save about 22 million litres of fuel and reduce GHG emissions by about 54,000 tonnes. This would be the equivalent of permanently taking 18,000 cars off the road.

Given our geographic spread, HB will never be a bastion of public transportation, but we have made an impressive investment in recreational cycling; we need to do the same with regard to work and chore cycling. And hopefully the current MyWay experiment, offering ‘on-demand’ van transportation, will spread in our urban centres. Finally, the buses we do have will all be required electric after 2026.

With respect to other consumption, we simply need to DO LESS as the project launched by Alex Tylee and George Miller urges. www.projectdoless.nz

In economically ‘well-off’ countries like NZ, each person accounts for 19 tonnes of CO2 equivalent per year. To stabilise global temperature at 1.5C, that number would need to be around 2.3 tonnes.

So, before we wave our fingers at cows, we might consider the methane we humans produce via our food waste. According to UN data, 20-30% of food produced is wasted. If global food waste and loss were a country, it would be the third-largest emitter of greenhouse gases on Earth.

New Zealanders generate the fourth highest amount of waste per person in the OECD. The amount of rubbish New Zealanders have sent to municipal landfills over the last decade has increased by a staggering 48% – some 740kg per person. In HB there is a disproportionately high volume of organic waste, which produces the nasty gases, going to landfill due to the amount of primary industry in the region.

The waste from residents of Napier and Hastings – 86,000 tonnes/yr – goes to the Omaruni Landfill, which at least has the distinction of operating a waste-to-energy project. It turns methane into electricity, producing about 1000 kilowatts of electricity a year, sold back into the grid, enough to power about 1000 homes for a year.

But local experts say half of that waste could be easily recycled or composted.

HBRC Climate Ambassador Pippa McKelvie-Sebileau notes:

“Everything that is brought into the house brings with it the emissions related to its production and functioning. If we’re going to think about individual and household actions we can all take, it can be useful to think about emissions this way. Over a third of our household emissions relate to our transport choices; and around a quarter relate to choices we make about what we eat or drink.

“Luckily, these are easier things to tackle. In many cases, we can choose to fly less, use public transport, car pool, walk or bike, or to reduce the number of trips by car that we make. We can think about the food we buy and try to choose products that have been locally produced. While this alone won’t solve the climate crisis, they do give us a sense of control and hope and can greatly reduce our household consumption profiles.”

Remember that regional profile at the start of this article, with HB reducing its emissions by 7.1%? In that same window, household emissions in HB rose 9.4%!

In short, curbing global warming is not all about producers, we consumers are the other side of the carbon ledger.

ADVERTORIAL

Not a toy!

Our personal transportation is one opportunity for each of us to reduce our carbon footprint. Yes, there’s the bus, the bike, the e-bike, but for most of us the challenge still comes from our petrol-powered auto.

So I took up an offer to ‘test’ drive a Lexus UX300e, the electric vehicle offered by Lexus of Hawke’s Bay.

Three words sum up my experience.

Smooth. Supersonic. Silent.

I haven’t driven a ‘high end’ car since moving to New Zealand, and so was a bit out of touch with the amenities I assume are now ‘standard’ on all such vehicles … petrol and electric. Automatic everything, from locks to touchscreens to low/high beams to corrective steering.

But putting all those features aside, I settled in for a weekend of EV experience, with my ‘fuel’ gauge telling me I had enough battery for 300 kilometres. The listed range is 360kms from the car’s 54.35kw battery (total power output of 150kw/201hp), but Oliver my Lexus sherpa told me 300-320kms was more likely in normal HB driving conditions.

So, let’s cut right to the chase … range anxiety. Since the car was a loaner, I had neither a home charger to fall back on, nor an account with one of the nationwide EV charging networks. Consequently, I was quite attentive to my battery reading!

Nevertheless, I did quite few trips from home base near the Red Bridge – out to Hygge in Clifton, over to Napier, a jaunt to Clive and into Hastings, and a couple of trips into Havelock village and back. The normal stuff of a weekend. And returned the car with nearly 90kms left on the battery indicator (having covered a bit over 200kms on the odometer). Over two nights I could have readily recharged if I had a home charger. So, no problem at all with day-to-day range. Anxiety cured.

My favourite gadget on this Lexus EV was the virtual ‘instrument panel’ that appeared to sit outside my windscreen above the hood of the car, just below my normal driving line of sight. It displayed just a view basics – the current speed limit (and whether I was over it), my speed, my remaining driving range, and my position in the roadway (the visual reinforcement of the auto-steering).

I felt like I was in the cockpit of a fighter jet. And this feeling was totally reinforced by the power of this EV. Instantly responsive to pushing the accelerator pedal, the car surged ahead. With the power and the ‘cockpit’ effect combined, I felt like – given enough runway – I could have taken off!

With amazing smoothness. No gears shifting – just seamless acceleration. Then, backing off the ‘gas’ pedal (but not braking), smooth deceleration as the motor automatically kicks in to slow the car and charge the battery in the process. The auto-braking feature could be set at four levels of ‘intensity’ to suit the driver.

And it all happens … noiselessly. So noiseless that the car has an ‘artificial noise’ feature you can turn on if you wish a reminder that you are in a moving automobile.

I’m a huge proponent of EVs. But I have to admit, I thought of them still as kind of ‘toy cars’ for those of us more concerned with GHG gas emissions than driving performance. Nice to putter around town in at 30 or 50kph.

However, this Lexus EV has totally changed my perception. Motorheads take note: this EV delivers more than enough power … in fact, your cockpit ‘over the limit’ signal is likely to get a workout until you get used to it!

Not that I encourage speeding, but if you occasionally put ‘pedal to the metal’, with an EV you’ll be doing it guilt free, at least as far as emissions are concerned.

Great article offering insights for everyone to be involved in reducing our GHG emissions. Just wish a car manufacturer would produce a more affordable no-frills ‘EV for those on low incomes. Not everyone needs/wants all the “whistles and bells” and this could significantly increase the uptake of EV’s.

Excellent article Tom!

Glad you enjoyed the EV. They are a great example of how the journey to carbon neutrality can add to our wellbeing and living standards, not detract.

Over time, we will need to find smarter ways to organise our communities and our lives, so that we don’t spend so much time ‘behind the wheel’ – or the heads-up display! But in the meantime, EVs are a great solution for those of us who can afford them, reducing most household carbon footprints by at least 1/3.

Cheers, Xan Harding

The usual compact comment on the Climate Change discussions. Very pleased to see our individual choices a target. Walking is great for those 5 – 10 block trips to the supermarket or the Farmers Markets but for the aged ones amongst us alternative transport is needed to get heavier items home.

So far nobody mentions home vegetable gardens. Until our move to a small multi story apartment e always had a home vegetable garden. Major benefits: cheaper food (though there are costs to gardening) better understanding of seasonality therefore less expectation of year long supply of some foodstuffs and possibility of preservation of foods. This all means training and tool supply.

Pleased to see mention of soil development rather than planting more pines. Have always felt it is too easy for heavy carbon emitters to take an easy way out.

Well done the majority of farmers who, in tthe main are much more responsible about reducing emissions than the average urban dweller .

Thank you Tom, an enjoyable read. It’s interesting to note, in addition, the carbon saving benefits of breastfeeding; there’d be no need to reduce animal numbers on farms if women received adequate support to breastfeed their infants for a time. More research is going on in Australia and Asia on this direction. Something very worthwhile to consider, seeing as less than adequate resources are given to this important matter.

As an urban dweller, I’ve switched to solar power, have only about 3-4 rubbish bags a year, have less lawn and more garden, 20 feijoas trees on my section and want to be an advocate and role model for my family. Keep up the good work on this subject.