When in November 2012, the Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI) reported that New Zealand’s fisheries were ‘in good shape’, many people with intimate knowledge of Hawke’s Bay fishing shook their heads in disbelief.

“How would they know?” says Wayne Bicknell. “Their stock reports are from 1997 data. And that data is from what was landed by commercial, and doesn’t include what was dumped.”

Rick Burch is clear, “We don’t have the research. All we’ve got is this slogan, ‘We’ve got the best quota management system in the world,’ and it’s bullshit.”

Rick has been commercial fishing out of Ahuriri for over 30 years, and Wayne is a member of the Hawke’s Bay Sport Fishing Club and Guardians of the Hawke Bay Fishery, a charitable trust promoting sustainable fishing. Both men are passionate in their endeavors to protect our fisheries.

Their frustration with the Ministry and the politics out of Wellington is simmering as they can’t understand why successive governments have done little to remedy obvious holes in the Quota Management System (QMS).

“We have to land every gurnard we catch, and the small fish end up in the dump or crayfish pots,” says Rick, “but when it comes to snapper, trevally, and tarakihi, we have to throw the small fish back, and those fish are not recorded, and most of them are dead.” Why the different treatment? Rick and Wayne don’t know. They’ve asked the Ministry, and they don’t know either.

“Another hole in the system is deem value,” says Wayne. Deem value is paying for over catching.

Rick explains. “Not long ago trevally was being caught over quota by 76%, and the Ministry made them pay a small fine per kilo for over-quota, but they sold it on for $8 to $9, so it’s worth it to catch what you want and pay the fine.”

“What’s more,” says Wayne, “instead of taking the over-catch off the following year’s quota, you start off with a clean slate, but if they under-catch, it gets passed over to the next year.”

Both men shake their heads, and I join them, because it doesn’t make sense.

“In a sustainable fishery you need past data to look back on,” says Rick, “but that hasn’t been available since the quota management system came in 1997. What they’ve done in other countries, like the UK, is they’ve been going up and down the same patch twice a year for 25 years, with the same net, at the same time, and after 25 years you see a trend. We haven’t done that so how do we know the fishery is sustainable.”

New Zealand’s reputation for sustainable fishing was badly tarnished by mismanagement of the orange roughy fishery in the 80s and 90s. And according to Dean Baigent, Director of Compliance in MPI, “Orange roughy is a good example of where market perception (of unsustainability) has pushed down the price.”

The consumer’s perception is in fact, a reality, and substantiated by the Supreme Court. In their 2008 decision, Elias CJ, Blanchard and Anderson JJ, ruled in favour of Antons Trawling Company Limited, who disputed the Minister of Fisheries right to reduce their Total Allowable Catch (TAC) of orange roughy.

“Of relevance was the absence of any evidence that orange roughy is under immediate threat,” said the Judgment of the Court. The Fisheries Act required an accurate population assessment. The Ministry hadn’t done the research, and couldn’t produce data to convince the Court. And this is a decade after the orange roughy boom collapsed.

In 2010-11 the total allowable commercial catch of orange roughy was 6,941 tonnes. In 1988-89 the catch was 54,000 tonnes.

Rick Burch fished for orange roughy. “We knew in 1987 it wasn’t going to last,” he says, “and we told the Ministry then, ‘You can’t keep pulling out 100 ton bags.’ They hadn’t done the research and assumed there were plenty of fish – then bang, gone. There was a 90% cut in quota.”

A consequential effect of the orange roughy collapse was that the big trawlers changed their operation to in-shore fishing.

100,000 hooks a day

“You can’t blame the fishermen,” says Rick. “But,” says Wayne, “Those bigger boats can fish in weather the smaller boats can’t, trawling bigger nets faster, setting more lines, and the Ministry don’t seem to appreciate that as fish stocks come down, size decreases, so you have to catch a lot more fish to make up the tonnage. That’s what’s happened with improved technology and trawler size.”

“I’ll give you an example,” says Rick. “When I came here 30 years ago this was one of the richest fisheries I’d ever seen, and I’ve fished all over the world. I was invited to go to sea with Sparky on the old Patricia Jane. I looked at the boat and the gear, and thought, ‘my God, this is out of the ark.’ The droppers were anchored with railway iron and the lines had 60 hooks, yet when we fished out from Bare Island in about 240 fathoms, 60 hooks went down and most would come back with a fish on. We had 10 droppers, 600 hooks went down a day, and there were five boats fishing that area.”

That’s 3,000 baits. “But then,” says Rick, “The big boats came, with the capability of setting 100,000 hooks a day.”

Not all the big boats came from the bust of the orange roughy boom. Some were specifically commissioned to maximize fish catch, like Chris Robinson’s 31 metre stern trawler Pacific Explorer.

Chris has a science degree, and has been a commercial fisherman in Hawke’s Bay for 30 years. His commercial arrangement with Ngai Tahu and other partners went bust last year. He lost his boats, and $12 million.

“What’s the state of the fishery?”

he responds to my question. “I believe it’s very healthy within the bounds of the QMS.”

Chris Robinson doesn’t accept there’s over-fishing. “Our quota management system allows a fishery to go into depletion and allows it, in time, to rebuild,” he says. “Quite a few of the major fisheries have undergone cycles of depletion. There are annual cycles in availability, and then there are major cycles of depletion, when for some unknown reason the fishery hasn’t been successful in recruitment. It may have spawned fine, but the conditions might not be right for the juveniles to feed, or the weather conditions, or currents are wrong, and the resulting year class from that recruitment might not be present, or small. This has happened to the gemfish, the hoki, and it’s happening now to the bluenose fishery.”

To a layman that sounds like over-fishing. But Chris assures me that, “Within the fishing sectors in the Bay, recreational and Mãoridom, very few people understand the life cycles of a lot of the fish. Gurnard for instance only live to three or four years old. John Dory was once believed to live to 35, 40 years but it’s actually only three years old. The significance of that is the fishery has an incredible capability of making benefit from the right spawning and growth conditions. When those significant year classes occur, everyone’s happy. It has to do with prevailing wind, water temperature and conditions.”

Chris Robinson’s explanation of why recreational fishers are finding it harder and harder to catch fish is not due to depletion, but sea conditions and weather. He says, “When we get poor weather the fish get dispersed. The fish are scattered, and commercial fishers wait for the fish to congregate into the areas where we know they should be. My observation is that when the fish are scattered it’s easier for the amateurs to catch them because they’re dispersed everywhere. Converse is when we’ve had long periods of settled weather, the fish congregate where the feed is massed, and unless the amateurs know where the fish are, they find it hard to catch them.”

Chris Robinson’s theory is difficult to reconcile with the experience of long time recreational fishermen in Hawke Bay. In a recent survey conducted by the Guardians of Hawke Bay Fishery, over 90% of respondents attested to a decrease in fin fish availability in the last five years, and 80% think that if current management continues the fin fish stocks will ‘have significant decrease’.

The net makes a difference

With overwhelming opinion that fish stocks in Hawke Bay are declining, the concern for our fisheries felt by Rick Burch and Wayne Bicknell is palpable, but rather than walk away, both men are determined to make changes.

“Many trawl nets are the same as they were at the turn of the century,” says Wayne. And he means the 19th century.

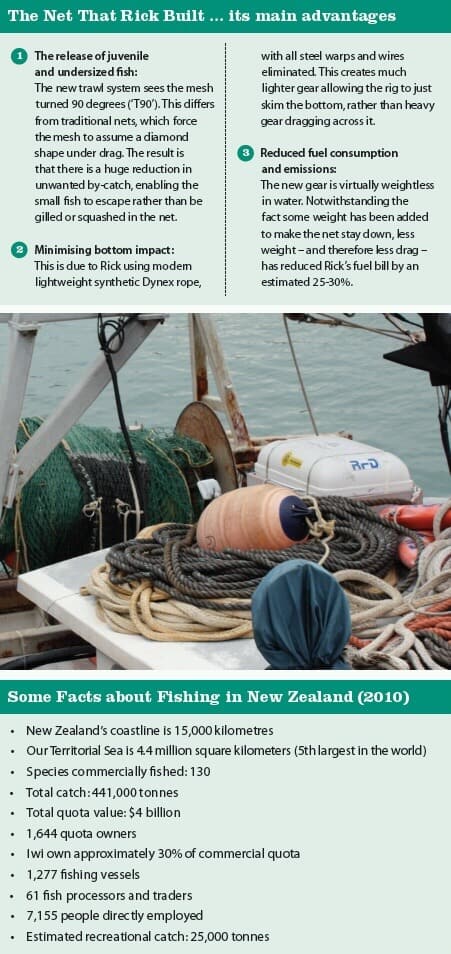

“We should be looking at using a trawl that’s like a spiders web; ultra thin, no resistance in the water, and that lets the small fish escape,” says Rick. A modest man, Rick Burch is hesitant to trumpet the qualities of a net he has designed, so I ask applied fisheries scientist Oliver Wade, who has been involved in the project.

“I was on-board for the first trial in 2011,” says Oliver, “and the net performed brilliantly. It’s world-leading technology. Thing is, that when a net is under pressure the mesh closes off making it impossible for juvenile fish to escape, but with Rick’s net the mesh stays open allowing escape. It has less drag through the water which saves on fuel, and has less impact on the sea bed. It’s a fantastic net.”

Further trials of Rick’s net are planned for the new year. Funding is always a problem. The latest trial is funded by Te Ohu Kaimoana – the Mãori Fisheries Trust, and in the past Guardians of the Sea Charitable Trust and Ngãti Kahungunu Iwi Incorporated have contributed.

Ngãti Kahungunu own quota and have a close relationship with Hawke’s Bay Seafoods, a major processor based in Ahuriri. The other major player in Hawke’s Bay commercial fisheries, Star Food Services, have already adopted elements of Rick’s net on their fleet.

Dr Adele Whyte heads the Iwi Fisheries Unit at NKII, and says, “Yes, we’re involved in testing Rick Burch’s net design. We’re investing time and money. We’re serious. At the moment we want to establish that the net works, it does what it’s meant to do, and that it will be relatively easy to modify existing nets, and get out fishing the next day. Our intention is that all fishers in the Bay use the modified net, and then hopefully it will be picked up across New Zealand.”

She continues, “If it’s catching fish of the sizes you want, and letting the rest go, that’s ideal. We want to know before and after, so we know for sure what’s being saved. If you want to get primary industries onside you need the data, so be it a scientist or a fisherman, they can see the data, see the results, and give it a go.”

I ask Adele her opinion of Rick Burch’s contention that the Ministry doesn’t have the data to accurately assess the fish stocks. “They’re not calculating that juvenile bio-mass that’s effectively gone and won’t breed because they’re dead,” she says. “So how much more productivity could we have in the system if we were able to release the juveniles, so they never get caught in the first place.

Most fishery scientists I’ve talked to say there’s flexibility in the system, even though they’re not counting every fish in the way they do the calculations. But discarding is a big issue. Apparently some of that is calculated, but it would be interesting to see what the calculations would show if you were able to factor that in. Would the Total Allowable Catch stay the same, or go up, or down?”

I mention the concern of recreational fishers, and the deluge of letters to the paper in recent weeks.

“The recreational sector doesn’t provide information of what they catch, so that’s a huge hole in the management. For some species, like crayfish and paua, the recreational take is as big as, if not bigger, than commercial. Recreational point fingers but everyone has to do their bit. We’re all in the fishery together.”

Ngãti Kahungunu is in a unique position as its interests encompass all sectors of fishing.

Says Dr Whyte, “We equally defend our commercial rights, as we defend our customary, and recreational rights.

So when there are lobby groups, we’re in all of them. There are definitely things we can do better but we’re working on those issues. Everyone needs to take responsibility.”

The Ministry man, Dean Baigent, admits that, “Everything isn’t perfect,” and he says an element is, “that there are 4 million fishing experts in New Zealand. It’s a spatial issue,” he says, “People are very protective of their patch.”

As Director of Compliance, he’s at pains to point out that, “Compliance isn’t about what you can’t get away with. It’s about best practice, and we’re trying to achieve this through all sectors.”

Of the future, Dean is optimistic. “Electronic technology, cameras on the boats monitoring the catches, is a possibility,” he says.

With few exceptions, there seems to be willingness from all interested parties to address and remedy the issues facing our fishery. But as Rick Burch points out, “The Ministry has to recognize there’s a serious problem, and they have to put aside the politics if we’re to move forward.”