Our councils are pretty much like the power company.

We pay attention to them on only three occasions – when they fail to deliver the promised service (major electricity outage … or, for councils, unsafe drinking water), when they inconvenience us (ripping up the streets … both guilty), or when they send us the bill (both guilty).

Otherwise, for most of the time, 99% of the population (I’ll come back to the other 1%) is happily walking our dogs, innocently enjoying our reserves or wine/beer/cappuccinos, worrying about our household bills, afflictions or kids, and only occasionally puzzling over – ‘How did that happen?!’ – when it’s too late to affect the outcome.

And that’s when issues of council performance and accountability generally make it onto the broader public agenda.

When accountability fails, it’s because much of the day-to-day governing process is inherently invisible … and designed to be that way.

Here are some of the forces at work.

The planning process

Fortunately the era of ‘big surprises’ is mostly over.

For example, our five councils in Hawke’s Bay have just finished their long-term planning process, yielding their 10-year LTPs. One would be hard pressed to find fault with the public consulting that was undertaken, either in scale or (in most cases) in detail provided. Councils have become commendably adroit in using social/online media to test their ideas.

[On the other hand, ‘consultation’ on Māori seats was a farce – no ‘pros and cons’ or context were provided, all done in haste to tick the consultation box in a (hopefully) legal manner.]

LTPs, with their associated rates increases and grand visions are where any ‘big ideas’ should surface.

There’s nothing wrong with grand visions when huge challenges confront the community – modernizing infrastructure, addressing climate change, mitigating social inequities in health care and housing, future proofing our regional agrarian economy. These are complex systemic challenges that will take many years and dollars – and often fundamental changes in entrenched habits and mind sets – to tackle seriously.

Rightfully, we should expect our councils to identify genuine needs, attach realistic costs against those, design and implement appropriate strategies and timetables, and then be held accountable for meeting explicit milestones.

But it’s this last part where the public gets shorted – before starting afresh and asking ratepayers to bear more, what progress has been made against past plans and promises?

Not surprisingly, LTP-time is the time when councils meekly apologise for not yet getting done what they said they’d do the last time around. Sometimes the reasons are excusable – Covid-19 being the most obvious disruptor.

But other unkept commitments may have simply been abandoned, their faults admitted after much wasted expenditure – e.g., the grand plan for the Napier (oops, National) aquarium, the Ruataniwha dam. Other projects get more complicated than first understood. Others slowed by lack of available expert help. Others are victims of public rebellion – Napier aquatic centre, Te Mata track. Others simply botched – e.g., CHB’s floating wetlands, museum sprinklers.

Whether forgivable or dumfounding, what is missing is any clear and consistent accountability mechanism for judging performance. Sometimes the responsible chief executives ‘move on’.

Sure, if things get bad enough, we can ‘throw the bums out’ at election time. But even that – to be targeted effectively – requires insight into what went wrong and who was accountable? And if heads should have fallen, perhaps they were within staffs, but these public employees are totally shielded from public scrutiny. No one was held accountable for the Havelock North campylobacter disaster at either the elected or staff levels.

As a former regional councillor, I appreciate that various reports are pulled together by staff to keep councillors reasonably informed (usually not high on any meeting agenda) … or at least manage councillors’ expectations. But these are not prepared in a style that would truly inform a more casual reader. Try this one in the council Annual Report you surely keep by your bedside: ‘LTP Level of Service Measures and Strategic Plan Outcome Targets’. Frankly, many of these reports bury in mind-numbing detail what’s actually critical to know.

Just taking the Regional Council, how would the average ratepayer know:

- Whether Lake Tūtira clean-up is on schedule or not? Ditto Karamū Stream and other former ‘hot spots’.

- What pollution enforcement actions have been taken, who are the culprits?

- What will the new batch of money requested for fixing the Ahuriri Estuary accomplish that the last batch didn’t – and why didn’t it?

- Is the ‘wall of wood’ arriving by train from Wairoa as scheduled?

- Of all the funding won by HBRC from the Ardern Governments, how much has actually been spent to date, to what effect?

- Right now, today, in what ways are our four territorial authorities failing to meet HBRC environmental requirements? What is the environmental cost of these regulatory transgressions and the ‘transaction costs’ of councils fighting each other over them?

My point? We don’t learn anything about what has not happened, excusable or not.

Let’s look at the biggest collective failure of local government in New Zealand for some insight.

Infrastructure debacle

Infrastructure – could there be a more deadly dull topic? Until people actually die!

The Government has been studying ‘3 Waters’ infrastructure closely – drinking water, wastewater and stormwater – and has concluded that the existing structure for managing these matters (i.e., leave it all in the hands of local councils) is an utter failure that must be replaced.

The latest cost for fixing decades of council neglect is now estimated at $185 billion nationwide (revised from ‘only’ $46 billion estimated six months ago), and that process, once set in motion will itself take decades.

As we’ve reported previously, a study conducted for our region conservatively estimates that more like $605 million will be required to bring Hawke’s Bay’s ageing water systems up to modern standards in terms of safety, reliability and environmental performance. That number has probably gone up just like the national one.

Here’s a case where councillors all over New Zealand have chosen to spend ratepayer money on glamour projects over core systems. Presumably at their service have been ‘asset management’ staffs who should have known better what was happening to their pumps and pipes and plants. But giving them the benefit of the doubt, they don’t vote the money.

The latest annual National Performance Review, from Water New Zealand gives a full picture of the scale of the problem and at least one clue as to how this has happened.

Councils with responsibility for water supply, wastewater and stormwater serving 88% of NZ’s population provided data for the report, including Hastings and Napier (Central HB and Wairoa councils did not participate).

Some ‘nuggets’ from the report, generally covering the 2020 fiscal year:

$2.3 billion was collected to fund water services, primarily through rates and volumetric charges. The average residential charge for water and wastewater services in 2020 was $878.88 (including GST).

The systems reporting have 88,108 km of piping, 4,023 pump stations, and 573 treatment plants. The average age of the pipes is 34-37 years.

Not surprising then that 21% of water supplied to networks is lost on its way to end use (and susceptible to infiltration)! Possibilities to mitigate water loss exist in at least 83% of service districts.

397 instances of non-conformance with wastewater treatment consents were reported, but only 29 enforcement actions taken against those. The report observes with understatement: “…formal processes to remedy non-conformance are rare”. The same experience with stormwater consents is noted.

Dry-weather wastewater overflows occurred 1,939 times in 2019/20. Another 1,278 weather-related overflows occurred in that period. And here is the unfortunate conclusion cited by the report about those:

“Current monitoring practices, knowledge of networks, and the wide range of approaches to regulation of wastewater overflows mean that, under current settings, it would not be possible to benchmark regions or engage in basic performance improvement metrics to drive better performance. Consistency in approach across all these areas would lead to considerable benefits.”

The consequences?

After Havelock North, we’re on top of drinking water, right?

The most recent Health Ministry report on drinking water safety released in June – Annual Report on Drinking-Water Quality 2019-2020 – found various ‘failures’ on the part of Hawke’s Bay councils to meet drinking water standards:

CHB: Pōrangahau failed the protozoal standards because the infrastructure available was inadequate. Takapau failed the bacteriological standards because sampling was inadequate. It failed the protozoal standards because there were gaps in monitoring. Waipukurau failed the bacteriological standards for unknown reasons. It failed the protozoal standards because there were gaps in monitoring and turbidity levels at times were too high. Farm Road Water Supply Ltd failed the bacteriological standards because sampling was inadequate. It failed the protozoal standards because compliance was not attempted.

Hastings: Hastings Urban failed the protozoal standards because the infrastructure available was inadequate. Waimārama failed the protozoal standards because the infrastructure available was inadequate and there were calibration issues. Whirinaki, Hawke’s Bay failed the protozoal standards because the infrastructure available was inadequate.

Napier: NCC’s municipal supply met all standards. However, Raupunga (supplied by Ngāti Pāhauwera Incorporated Society) did not take reasonable steps to protect source water from contamination, failed to meet drinking-water monitoring requirements for the supply, failed to keep adequate records, failed to adequately investigate complaints and did not take all appropriate actions to protect public health after an issue was discovered. It therefore failed to comply with the Health Act. Raupunga failed the bacteriological standards because sampling was inadequate. It failed the protozoal standards because compliance was not attempted.

Wairoa: WDC’s municipal supply met all standards. However, Blue Bay failed to provide adequate safe drinking-water, did not take reasonable steps to protect source water from contamination, failed to meet drinking-water monitoring requirements for the supply, failed to keep adequate records, failed to adequately investigate complaints and did not take all appropriate actions to protect public health after an issue was discovered. It therefore failed to comply with the Health Act. Blue Bay failed the bacteriological standards because E. coli was detected in 100 percent of monitoring samples and sampling was inadequate. It failed the protozoal standards because compliance was not attempted.

Apart from politically-generated neglect by our local elected councillors (i.e., fear of rate increase, infatuation with more visible public baubles), how has this state of affairs developed? Could it be incompetence?

Here is one of the very first observations in the Water NZ Performance review:

“The lack of information on staff training and qualifications is quite surprising and, possibly, quite concerning. Going forward, the thought is that the Regulator will be looking for assurances that the industry is employing the right people with suitable qualifications and training, and a commitment to staying up to date with the latest technologies. Consulting companies have been managing this type of information for some years because it is one of the key attributes when selling services, so there is no reason why local government organisations cannot do the same.”

Under the circumstances, one would think that our local councils would be eager to demonstrate that their teams were totally ‘up to snuff’ when it comes to 3 Waters management.

To the contrary.

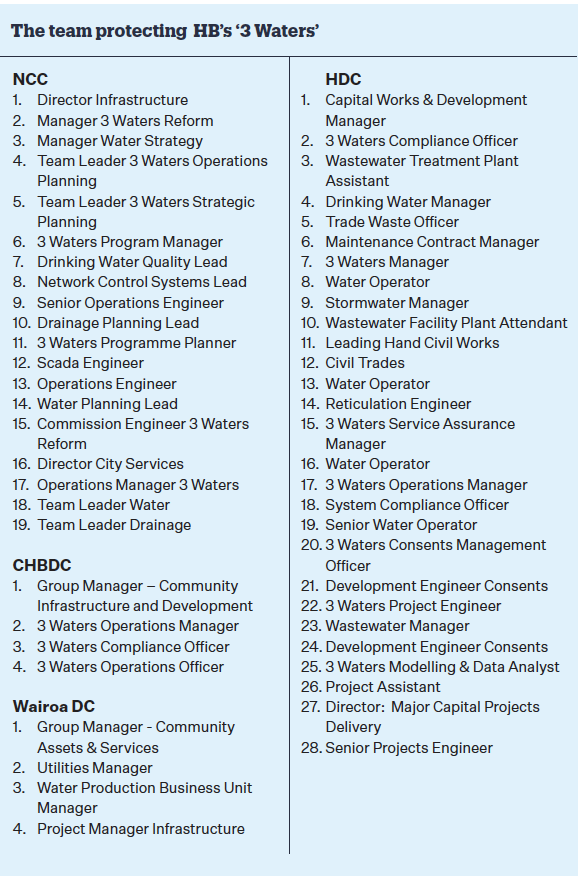

Using the Official Information Act, BayBuzz asked our four territorial authorities to identify the relevant professional credentials held by the staffs currently managing our ‘3 Waters’.

Specifically, we asked: “BayBuzz is hereby requesting from your council a list of the personnel currently employed to manage ‘3 Waters’ service implementation (and associated council policies), their official titles, and the pertinent academic/professional credentials they hold to inform their handling of these responsibilities.”

Each council replied with only a list of job titles (see sidebar) – no qualifications were provided for a combined team of 55 public employees. In each case, councils declined to provide qualifications on grounds of privacy. Here for example is the rationale from NCC:

“Council has decided to withhold the individual names of employees and their academic/professional credentials under sections 7(2)(a) and 7(2)(f)(ii) of the Local Government Official Information and Meetings Act 1987:

– to protect the privacy of natural persons, including that of deceased natural persons; and

– to maintain the effective conduct of public affairs through the protection of such members, officers, employees, and persons from improper pressure or harassment.”

The councils take the view on this request (and most other OIA requests that attempt to pinpoint internal accountability), that privacy considerations are not outweighed by the public interest.

Leaving aside names, without any disclosure of staff (i.e., public employee) credentials and professional competence to manage our water safety, obviously the councils’ responses are worthless. Your doctor hangs her plaque on the wall for the world to see, why not your ‘3 Waters Compliance Officer’? Your councillor can be an idiot; your ‘Operations Manager – 3 Waters’ better not be!

There is no greater escape from accountability than anonymity.

The staff shield

This shielding of staff is not unimportant.

Council staffs generally run the show. They outlast and work harder than most councillors. They control the information flow. They develop their own sense of what needs to be done (with or without public input). And they can get much of it done under the radar, with trusting councillors mostly oblivious until the sheepshit hits the bore.

So it comes as no surprise that council staffs have their own agendas, plans and timetables, which they’d like to pursue – as anonymously and unimpeded as possible – in a cloud of 10-year plans, mysterious reports (vouched for by compliant consultants) and glossy strategies with aspirational titles.

And they are accountable only to their chief executive – they are not even ‘fair game’ for councillors, elected to protect your interests. So even when the same names surface (at least to insiders) over and over for abuse of process, unresponsiveness or outright incompetence, there’s nothing to be done unless the CEO is so motivated … but running large bureaucracies requires HR dexterity.

The second reality intersecting with the first is that supplicants with agendas, who know how the council system really works, are always knocking at the door, looking to advance their agendas, which aren’t necessarily bad, but often private. These are the 1% I mentioned at the outset.

They need council support for their objective and they plot and organise to get it, with the first step being planting the seed and winning the approval of a council bureaucrat. This is not evil doing on the part of those needing council help, but it is clearly a reality that favours the insiders and it can be abused … particularly when plans are ‘co-hatched’ to avoid official public notification.

And before you know it, there’s a staff recommendation for a new track, or hub, or zoning variance, or memorial flame relocation, or closure/opening of something, whatever.

Steps toward accountability?

Where there’s a will there’s a way.

Perhaps a simple ‘Follow the money rule’ applied to any new funding request and duly reported. Like: “What money has been committed previously for this purpose (and spent or not) and what has been the result against the predicted outcome?”

How about an annual report from each council in plain English titled: ‘Top ten things we tried to do but failed.’ Why not formally report non-performance in a format not buried in ‘progress’ gobbledygook?

Maybe a small ombudsman unit, jointly funded by our five councils, with an ample hunting license and open door to council critics.

Maybe a public log, posted online, of meetings held between council staff (at least senior managers) and outside parties.

Maybe a reinterpretation of the ‘privacy protection’ of public servants.

Whatever approach is attempted, the public good – which requires transparency – must trump bureaucratic convenience. Sunlight is the best disinfectant.

Other ideas welcome from readers!

Brilliant! Thanks so much for this enlightening article. Hopefully we’ll collectively find a way to act upon the ideas you’ve floated.

Tom – a great article. I’m distressed that this ‘old labour’ government think that top-down centralisation will deliver better outcomes for health or water. This approach will make bureaucrats more distant and less accountable to our community. The right principle is that control is devolved to the lowest sensible level. I like a world where a bureaucrats’ kids go to the same school as mine and they drink coffee in the same cafe. It gives them a lot more skin in the game.

Brilliant.

Time to call a spade a spade. Time to rationalise the number of bureaucrats filling jobs that are irrelevant, and get back to basics and actually do stuff that is important.

Thanks, Tom. Great in-depth article. So useful to have your view of having been ‘on the inside’. Many of your concerns I carry too.

In the council-provided list, I don’t see NCC ‘Manager, Environmental Solutions team’. These are the small team who do the water monitoring in NCC stormwater waterways/Ahuriri Estuary, liaise with industry to educate and negotiate ‘ environmental management plans’ to treat waste at source, respond to waterway spills (24/7), clean up waterway spills, and decide whether to prosecute based on their own resources to be able to do that, eg. people, time, $$, likelihood of winning a case – it’s a high cost to a small team to follow through. That small team is also dealing with the recycling issues.

NCC currently have their first prosecution in the District Court, for a pollution issue into Tyne St waterway (think drain) 7 months ago. I’ll be watching the outcome with interest. Somehow the NCC need more ‘teeth’ to follow through in these situations.

Angie Denby

Ahuriri Estuary Protection Society

interesting that NCC “complies” with water standards… yet it seems half the time half the people wouldn’t want to drink it! obviously (one assumes) this is because the “discolouration” problems are not actually a health risk, in terms of what is measured. which begs the question: is what is measured/accorded risk status in the water a too-narrow band? and is that part of the problem?

WOW? What an excellent, well researched, well put together article.

You are so desperately needed on Council, Tom!

Thankyou Tom for providing this information. It certainly is an eye opener when you see the amount of resources/staff allocated to the 3 Waters mahi although I am sure not all information has been supplied as alluded to in other comments. I would like to see what consents have been allocated by the various councils to themselves and the monitoring outcomes of these consents and if they have been monitoring themselves. I am interested in further information on Raupunga and will follow up. I am quite sure it does not sit under NCC. Thank you for your excellent article.

Great article. What is lacking is competent people and the loss of competence is directly proportional to the mismanagement at the top. For example, the previous CEO of Water NZ stated to me that he had no idea of how to treat water and nor does he have any knowledge of water treatment. He stated that he employed people for that job. The problem with that is as the employer he has no ability to know if the persons he employs is capable of the job as he has stated that he has no knowledge of water treatment. Clearly he is not competent to know if the employees are actually competent or just a blowhard. Here lies the real problem. We have idiots in charge making statements that we believe to be coming from experts but in fact, the statements are coming from incompetent people often based on hearsay as opposed to real science. We have seen absolutely stupid numbers being put forward for the remediation of the NCC water supply. The reports on the subject appear to be written by a student as opposed to a professional. In my humble opinion, these consultants are doing nothing more than lining their pockets from the public purse and having worked with most of them I have no confidence that they can deliver for our community. I agree with Paul Paynter and that we need to employ competent people who live in our community having skin in the game. Water NZ is a waste of time as they are remote from HB and can do nothing better than make stupid generalised statements that aren’t applicable to our water supplies. As all communities around NZ are realising the fact that water is an extremely complex subject and that no two waters are the same. Our water issues will not be resolved with the addition of chemical solutions. The chemical treatment solutions only add to the pollution problems. Central government feel that adding Chlorine and fluoride will fix our issues, they are so wrong. We only need to look at Carterton and the ongoing E.coli problems even at highly elevated chlorination levels, chlorine failed to disinfect the water. Clearly, chlorine does not protect municipal water supplies from infections like E.coli. Chlorine is not and will not be a solution and this is why advanced countries have or are turning their back on chemical solutions. How many failures will it take before we as a country smarten up and look to properly upgrade our water supplies with 21st-century solutions and not 19th-century solutions?

Thank you, Tom.

Cogent, easy to access the information and thought provoking.

I hope you intend to stand for the newly vacant HBRC seat.

It is my understanding that accountability for risk management of coastal inundation has been sheeted home to the regional council by the Asher ‘review and recommendations for the Clifton to Tongoio coastal hazards strategy joint committee’.

The present LTP seems to be being progressed under any number of processes that remain lacking in accountability. I.e.: LTP’s, HPUDS, the Hastings District Plan Review, changes to the RMA, and a new ‘Spatial Plan’. These processes are progressing without significant input from informed professionals (resource consent applicants or otherwise). Such professionals should be invited by a regional council councillor to contribute at an early stage to illustrate accountability and transparency.

I volunteer.

Tony Maurenbrecher (licenced Surveyor)

Excellent article Tom, well overdue to be aired. The ‘moles in their holes’ need smoking out & you’re the firebrand to do it. I’ll vote for you

Wairoa Mayor Craig Little takes exception to the characterisation of Wairoa’s drinking water status in this article. We note this assessment is taken verbatim from the MOH’s Annual Report on Drinking-Water Quality 2019-2020. We have asked MOH to comment as well.

Here’s Mayor Little’s retort:

I do not understand why Raupunga’s water supply would come under the Napier City Council? Raupunga is in the Wairoa district. This is a private water supply that the Ministry of Health, Wairoa District Council and QRS have supported. Earlier this year, using the Three Waters $11 million, Wairoa District Council paid $12,000 for improved chlorination and dosing of the Raupunga supply and have also supported the scheme through staff and other contributions.

With regards to the Blue Bay supply it was not mentioned that this supply has never supplied a home and has been disconnected since late 2018.

The original Blue Bay water supply was built by a private contractor to meet the requirements at the time. Council inherited the water supply, and it does not comply with today’s standards. The Wairoa District Council has no records of this water supply ever supplying a home.

Council has been diligent communicating to ratepayers the costs involved in upgrading the supply to meet drinking water standards.

The Blue Bay drinking water upgrade will remain on hold until the details of the Central Government Three Waters review have been released and Council has analysed the implications.

While the project is paused Council has chosen not to charge water rates, being the capital, upgrade costs and catchment charges, to Blue Bay property owners.