A partnership between Hastings District Council, government ministries, mana whenua and community groups has been established to address the acute shortage of affordable housing in Hastings and its social consequence of homelessness. December 2022 is the third anniversary of the Hastings Place Based Housing Plan.

BayBuzz investigates how well it is working.

‘Place-based’ acknowledges local challenges require local solutions and best outcomes are achieved when community stakeholders have a seat at the table with local and central government.

The Plan’s core partners, who meet six weekly, are Hastings District Council (HDC), Ministry of Social Development (MSD), Ministry of Housing and Urban Development (MHUD), Kāinga Ora, Te Puni Kōkiri (TPK), Ngāti Kahungunu Iwi (NKII), Te Taiwhenua o Heretaunga (TToH), Heretaunga Tamatea Settlement Trust (HTST), and Hawke’s Bay District Health Board (HBDHB).

The ministries

MSD, the social welfare ministry, is responsible for assisting homeless into accommodation. They administer the Emergency Housing Special Needs Grant for the cost of emergency accommodation, mostly in motels.

More than fifteen hundred people are currently in emergency housing in Hastings.

Highest earners from the Special Needs Grant in the year ended March 2022 were Hastings Top 10 Holiday Park, $3.08m, and Frimley Lodge Motel, $1.15m. Top 10 has imported container houses to meet demand.

MSD also manage the Public Housing Register, the waiting list, with over 800 current applicants in Hastings, and MSD determine income-related rents for public housing tenants (25% of net income).

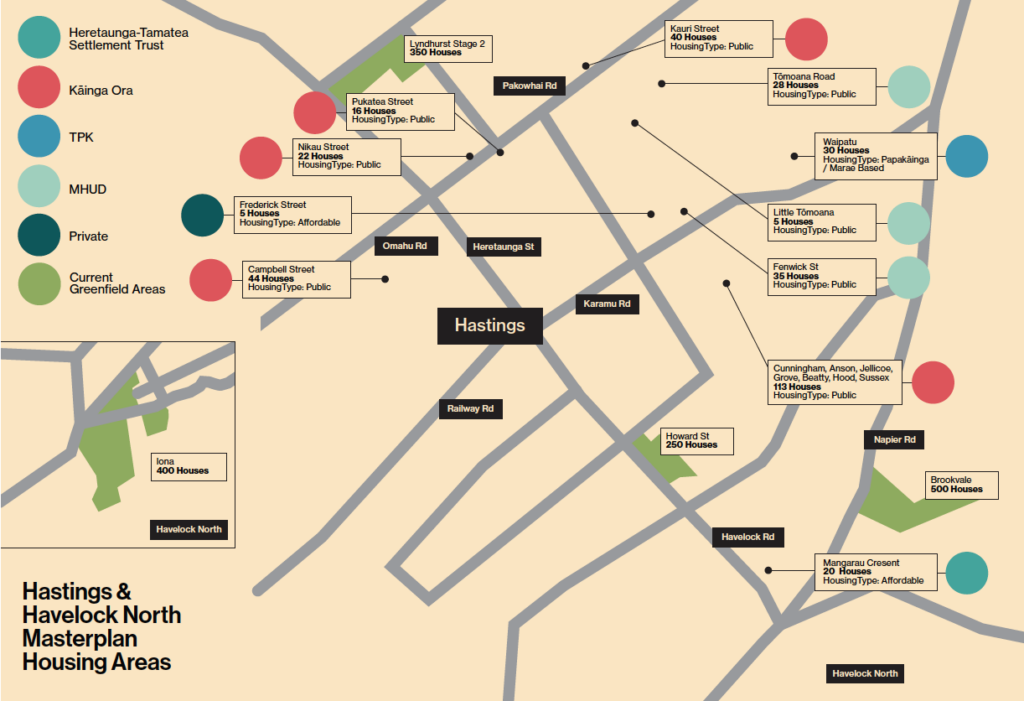

Kāinga Ora manages the social housing portfolio, renovates existing homes, builds new social housing, and is funded by MHUD. In Hastings, since September 2020, they have delivered 188 social houses, 62 transitional, and 133 houses are currently in design and construction stages. (KO 22/07/22)

At a hearing before Commissioners at HDC in September, a Kāinga Ora spokesperson said their 2021-24 target of 400 homes was on course, and that 75% of need was for one and two bedrooms.

Dotted throughout older Hastings suburbs are new Kāinga Ora infill houses, singles and multiples. In Raureka and Mahora, clusters of up to 45 houses, one to six bedrooms, built to Homestar 6 standard, are a model of cohesive social housing design and amenity. In Flaxmere, close to Te Aranga Marae, social, transitional, and private housing are intermixed.

Transitional housing was introduced in 2017 to provide short-term housing for those transitioning from living in substandard accommodation, mostly motels, to finding secure housing. MHUD contracts with developers in transitional housing builds.

In Flaxmere, Soho Group, owned by Sam and Jonathon Wallace, built 18 houses, and at Stortford Lodge, Auckland based Trevor Pearce, has just completed 14 two-bedroom semi-detached dwellings.

A feature of the Pearce build is a Council requirement to install retention tanks to reduce the impact of heavy rain on the stormwater system.

Properties are secured by MHUD with purchase or long-term leases.

TW Property Group, owned by Simon Tremain and Cam Ward, recently sold a cul d’sac development of 28 houses in Mayfair to MHUD. Half are transitional housing managed by Te Taiwhenua o Heretaunga, and half are social housing managed by Kāinga Ora. A feature of the TW build is that ten of the homes are accessible catering for people with mobility needs.

TW Property Group is the parent company of HB Construction, a major contract builder for Kāinga Ora and active in building medium density cluster housing for the private market.

Te Puni Kōkiri (TPK), the Ministry of Māori Development, supports and funds Māori housing initiatives, especially papakāinga, the building on ancestral land with multiple persons ownership.

Having no cost of land component, papakāinga gives whānau easier access to affordable housing, $350-$450,000. Also assisting affordability are favourable mortgages from Kiwibank being underwritten by Kāinga Ora. Currently no deposit is required for a loan below $200,000, but a deposit requirement of 15% for every dollar borrowed above $200,000 applies.

Throughout the district, at Waimarama, Kohupatiki in Clive, Waipuka Ocean Beach, Bennett Road in Waipatu, Paki Paki, and Bridge Pa, papakāinga are completed, under construction, and planned.

At Waipatu Marae multiple infill papakāinga homes are dotted among the existing houses, and across Karamu Road, on land previously the site of Clyde Potter’s Epicurian Supplies, Waipatu are to build up to 30 homes.

Hawke’s Bay District Health Board (HBDHB) is partnered with TPK in delivering the Child Healthy Housing Programme, which upgrades Māori owned homes to be warmer and healthier, preventing childhood respiratory illnesses and rheumatic fever.

The Council

In the first year of the place-based plan, a strategy document on Hastings District’s housing aspirations, policy, and achievement goals was developed in collaboration with partners. The Medium and Long Term Housing Strategy, Kāinga Paneke, Kāinga Pānuku, was signed jointly by Mayor Sandra Hazelhurst and Iwi leader Ngahiwi Tomoana in February 2021.

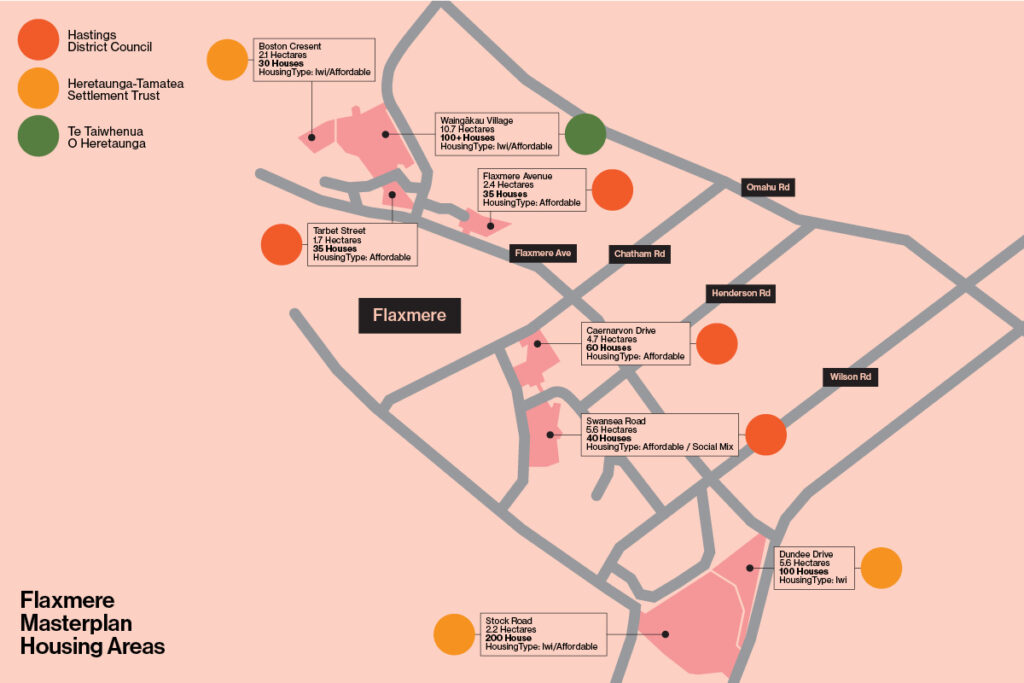

Kāinga Paneke, Kāinga Pānuku, is a detailed masterplan of housing development in Hastings District with a goal of meeting projected demand of 7000 new houses over the next ten years, 2500 of those being medium density.

HDC actively encouraged medium density cluster housing and smoothed the consent process with their 2020 Residential Intensification Design Guide, and HDC was one of the first councils to include papakāinga building codes in its district plan.

HDC is also a developer. Three sites in Flaxmere, yielding 135 sections, are being formed in stages. Council have contracted out the infrastructure build, roading and services, and are currently in negotiation with developers.

By end 2022, it is Council’s intention to have entered into agreement(s) with building developer(s) who will buy the land and build new affordable housing. HDC have stated they would like to see 20% of homes as dedicated social housing.

Being the local authority, it is HDC who collate and publish regular updates of the place-based partners’ work stream. The initial goal of 650+ homes, currently stands at 499 either completed, under construction, or site ready.

HDC hosts the six weekly meetings of the place-based partners, and chief executive, Nigel Bickle, appointed in 2019, is well qualified for his role, having had a thirty-year career in the civil service with senior positions in the Ministries of Housing, Immigration, and Social Welfare.

Mana whenua

Ngāti Kahungunu are represented in the partnership by NKKI, the Iwi’s governance and enterprise organisation. Nigel Bickle credits former NKKI chairman, Ngahiwi Tomoana, as instrumental in Hastings being chosen as the first district to trial a place-based approach to housing supply.

NKKI are active in the housing sector through their land development and construction company K3 Kahungunu Property. In Napier, K3, is in partnership with government (MHUD) and a private developer (David Colville) to lead the staged subdivision and building of up to 600 homes, expected to begin in 2023.

K3 has an emphasis on providing training opportunities for Māori by way of trade apprenticeships, and creating business opportunities in the design, materials, supply, manufacture and construction processes.

In another project, agreed June 2022, K3 Kahungunu Property has partnered with MHUD and Te Puni Kōkiri, who are funding $45.3m to build 131 new homes in Ngāti Kahungunu rohe, which stretches from Wairoa to Wairarapa. A long-term project, where, when, and how many of those houses will be in Hastings, has yet to be determined.

Heretaunga Tamatea Settlement Trust (HTST) is the governance body managing the Treaty of Waitangi settlement with the Crown. The settlement acknowledges multiple Crown breaches in land purchases that left Heretaunga Tamatea whānau virtually landless.

One of the Trust’s first investments was the February 2020 purchase of 22 hectares on the eastern fringe of Flaxmere. Combined with a neighbouring 5.6ha site HTST are planning a subdivision yielding up to 400 homes.

Discussions about partnering with relevant ministries is underway and HDC is supporting the land use plan change.

Two more properties, in Havelock North and Flaxmere, were purchased in June 2021, and are now included in the place-based plan work stream, supplying around 50 new homes.

Te Taiwhenua o Heretaunga (TToH)

Our meeting begins with karakia, a prayer, invoking spiritual guidance and protection.

Te Taiwhenua o Heretaunga, “is a Kaupapa Māori organisation. There is philosophy in everything we do,” says chairman Mike Paku. “Our basic core values are the building blocks on which everything sits. We don’t do anything without referring to our kaupapa, our philosophy.”

Established in 1987 as a charitable trust, Te Taiwhenua o Heretaunga (TToH) is the largest of the six taiwhenua in the Ngāti Kahungunu rohe, with over 9,000 registered members.

From humble beginnings in a Flaxmere shed, TToH is now based in a sprawling complex, previously the DB Heretaunga Hotel, and provides a range of services in health, education, pastoral care, and housing, has 430 employees, and 2021/22 revenue of $53m.

In the housing sector, CEO Waylyn Tahuri-Whaipakanga says, “We are in a unique position, working across the whole spectrum, from homelessness to being real estate agents selling homes.”

The real estate arm of TToH is Waingākau residential subdivision of 120 homes in west Flaxmere.

The homeless support element, while always being a TToH service, has recently expanded into emergency and transitional housing.

“There’s been homelessness before but now we have homelessness on mass. We’ve always supported homeless whānau, but it’s only in the last four years we’ve had transitional housing. “Emergency housing used to be for victims of domestic violence, needing to move. Now there’s such a chronic shortage (of houses) we have whānau with both parents working, who lose their rental, can’t find another, and end up in emergency housing in a motel.”

Working closely with MHUD, MSD, and Kāinga Ora, TToH are currently supporting whānau in both emergency and transitional housing. With transitional housing TToH, “manages the tenancy, and the social needs of the whānau. We talk about how to be a good tenant, and how to prepare for permanent tenancy. It’s a wrap around service.”

Building community and relationships, whānaungatanga, is a core of TToH kaupapa.

Serena Hakiwai, communications manager illustrates. “An aspect of the Korowai Street transitional housing is it sits alongside Waingākau, our subdivision development, and when the Korowai whānau had all moved in, the Waingākau whānau held a pōwhiri at Te Aranga Marae to welcome them into the community.”

Waylyn adds, “We want people to have a buy into the community, where they know their neighbours and support each other. We’re forming community together where everything’s joined up.”

That Māori are disproportionally excluded from secure housing is an issue TToH are actively addressing with home ownership the ultimate goal.

Mike Paku imparts some background. “You have to remember,” he says, “for a long time Māori have been told you will never own your own home. That’s the message they’ve been given which has led to choosing a lifestyle with the attitude, if I’m never going to own my own home, why should I save for a deposit, may as well enjoy all the consumables.”

It hasn’t always been so, and Mike reflects on his youth. “When I first went to work, I was encouraged by our kaumatua to get my own home, and to talk to Māori Affairs about the pathway.”

The Māori Affairs Department had a property division offering equity assistance and low interest loans but, “when devolution of Māori Affairs took place the housing section wasn’t replaced (1989).

Devolution also saw the closing of the freezing works which were the biggest employers of Māori in the region.” Whakatū closed in 1984, followed 10 years later by Tomoana, with a combined loss of 4500 jobs.

The economic and social damage for Māori from the free market policies of the 1980/90’s was severe and lasting.

The latest census (2018) cited the proportion of people living in owner-occupied dwellings as 64.3% overall. For Europeans it was 70.5%, for Māori, 47.2%. The earliest census data, from the 1930’s, showed 70.5% of Māori lived in owner-occupied dwellings. (info@stats.govt.nz)

“Clearly,” says Mike Paku, “mainstream have failed Māori in housing and there had to be another pathway.”

Waingākau is a destination on that pathway but the journey hasn’t been easy. “There was a lot of push back from the community in west Flaxmere, from those who had built on Kirkwood Road. There was a fear that our development would pull values down. Usual stuff. They’re Māori houses so they’ll be slums. We had to get over that.”

Get over it they did. Twelve houses are completed, several are under construction and forty sections are formed and serviced, ready for the builders.

Waingākau is different from normal subdivisions. “Our model is far more complex than the usual developer who prepares the sites and sells. We start with the whānau .”

Serena Hakiwai explains one initiative. “Sorted Kainga Ora has a great success rate in getting people housed so we made the decision to run a programme internally. We had 42 applicants. There’s a site tour on right now.” All aspects of home ownership are covered, budgeting for saving a deposit, dealing with banks, lawyers, building contracts and catering to individual needs.

Also assisting Waingākau first home buyers is a shared equity scheme, funded by Te Puni Kōkiri, which offers top-up deposit loans, interest free for 15 years.

Of the place-based partnership, CEO Waylyn Tahuri-Whaipakanga says, “For the first time we are kept informed about all the housing developments across the district. We support each other. If there are difficulties we’re working through, someone else might be able to support us, and we are able to support others.”

Mike Paku concludes. “All the partners have a shared vision to uplift whānau by putting them into homes. It’s a shared vision we all work to enable.” And he adds, “What is good for Māori is good for everybody.”

No home

In a timber panelled room at Saint Andrew’s Hall on Market Street are a row of lockers. The keys are held by rough sleepers. The lockers are the closest they have to a home, somewhere they can store valuables, clothes, medication, sleeping gear.

The initiative is part of the support offered by Warren Heke who recognised the need when he became Pastor of Hastings Church. “One of the first things I realised was that the best place to impact the community was right at the front door. There were people in very real need, disenfranchised, disconnected from community.”

The Church in Heretaunga Street invited rough sleepers to drop-in, to rest, have a coffee. “On Sundays the congregation shared lunch after morning service and because guys had been coming to the church during the week, they came one Sunday and asked what was happening. I explained and invited them to eat with us. They piled plates with food and stuffed food in their pockets.

“It was a meeting of two very different cultures, one of normal society and one of desperate need, which led me to thinking about how we could connect.”

Discussion with the congregation was challenging.“They’re very un-polite.”

“How polite would you be if you were starving?”

“They’re so unclean and smell.”

“You’d smell too if you had nowhere to wash.”

Christian values prevailed and the congregation welcomed their homeless guests, who soon learned there was enough food for everyone, and containers were provided so they could take some away. Later homeless were offered use of the kitchen and laundry.

“We earned some credibility with a section of our community that was notoriously hard to engage with by getting beyond the transactional relationship.”

Transactional relationship? “Yes, look at all our Social Services. They define people based on what they lack, and if they reach a certain criterion they are supplied with their need, so it becomes a transaction where the currency is your lack.”

By building trust and mutual respect Warren Heke says, “guys share information about themselves they’d never normally talk about. Backgrounds, relationships, trauma, addictions. It helps us, help them, in making good decisions about their caring.”

In talking to rough sleepers about their housing needs, Warren says, “The standard Kiwi dream of a house on a piece of land is the farthest from their aspiration. The responsibility of that situation is overwhelming. When you’re managing a raft of problems you don’t want to add any more. For people with addictions and mental health issues managing any sort of accommodation can be difficult.”

What about a shelter where they can sleep, wash, cook? “Shelters are an anathema to many, especially councils. There’s almost a stigma attached to having a shelter in your city, as if it means you’re not dealing with the problem.”

His attitude is pragmatic. “We can’t solve homelessness, but we can help lessen the suffering.”

Warren Heke encountered the Hastings Place Based Housing Plan in 2020 when in discussions with council about homeless policy in the Medium and Long Term Housing Strategy, Kāinga Paneke, Kāinga Pānuku.

“The government’s national plan, Housing First, wasn’t working. They were trying to solve a local problem with a national solution. It doesn’t work that way. We needed a local solution.”

Council commissioned a report on homelessness in Hastings. “The results of the study was to create a day space where the homeless community feel safe, connected and included.”

A partnership was formed. “I’d met the Bishop of Waiapu at council, and together we called a meeting of the faith-based communities to talk about homelessness and what, as people of faith, we could do to help.” Consequently, Anglican Care Waiapu, council, and Warren Heke had, “weekly meetings all year and together, collaboratively, we’ve worked out what needs to happen.”

Their goal for the new premises “is to create an integrated community hub. Integrated in the sense of bringing the communities of providers and users together, with a common way of connecting.” Already service providers, like MSD and TToH, come to their homeless clients in the hall, and a health service is provided on site thrice weekly.

A heads of agreement has been signed, “where I will lead the response, and council and Anglican Care Waiapu will give me the resources and support to make it sustainable, and to do it well.” What is different about this initiative is that Warren Heke is not a service provider. His role is “to host and chaperone” the relationship between homeless and the agencies that can help them, and as such, “doesn’t fit in to any of the existing funding pathways.”

At a recent meeting with council and Anglican Care, Warren was introduced to an MHUD place-based plan representative from Wellington. She told him she’d heard about his work, and asked, “Is there anything we can do to help?”

He told her their “budget was only half-way there.” She asked him to send the details, and “I’ll see what we can do.” Connections and relationships are core to the place-based approach.

As Warren Heke points out. “I’m a Pentecostal, partnering with Hastings Council and an Anglican bishop, working from a Presbyterian building, and the CEO of Anglican Care is Catholic.”

Photos: Florence Charvin