All Black Norm Hewitt used a recent NZ-on-Air documentary, Making Good Men, to unpack his violence and the day he unleashed the volcano inside and delivered a substantial pummelling to a classmate.

When Hewitt is just a small child in the story, he recounts hearing his mother being beaten by his father. It’s his mother’s voice that resonates.

She says: “Not in front of the children.” He’s five. By nine he’s gone from witness to victim. At 14 he’s become the bully.

Telling the story that’s the crux of the film Hewitt says: “I lost so much control. It reminded me of what it was like looking into my father’s eyes when he was standing over me and I knew he couldn’t stop.”

In turn his father talks about his own childhood beatings at the hands of his father:

“He pulled me out from under the bed and gave me such a thrashing I thought I was going to die,” he says. “I had no role model to show me it was different.”

A Hawke’s Bay story

Hewitt’s is a Hawke’s Bay story; he was born in Hastings, raised in Central Hawke’s Bay, schooled at Te Aute. His mother is Māori, his father Pākehā.

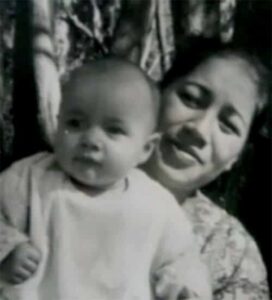

Early on, the film throws up a black and white still of Hewitt as a baby, a typical Hawke’s Bay baby in many ways, he’s not from a stereotypical ‘poverty’ household, he’s cradled in his mother’s arms, his father puts food on the table, there’s family around.

“I lost so much control. It reminded me of what it was like looking into my father’s eyes when he was standing over me and I knew he couldn’t stop.” – Norm Hewitt

Let’s look at this baby: born with 50 million neurons, he will never produce any more. What he will do is grow neural pathways, and fast.

Paediatrician Dr Russell Wills explains the link between this and what happens next:

“From 0 to 3 years you make millions of connections every minute. When needs are met promptly and appropriately we learn to trust, to delay gratification. If you are born into a stressful situation you are still making connections but they are different: gratification needs to be immediate, there’s a strong flight or fight reflex, there’s no trust. And that is hard-wired.”

Breaking the cycle

Hewitt’s story happened 40 years ago, but elements of it are playing out through Hawke’s Bay every day. We have one of the highest rates of family violence in the country, and with much anecdotal evidence to say abused children – or even children who are simply witnessing family violence – grow up to abuse, it’s a vicious cycle.

Everyone, from the health sector to the Police to social services to Women’s Refuge accept this as fact, but there is very little long-term help. There are ‘bandaids’ and the allegorical ambulance at the bottom of the cliff, but no robust, on-going, government-resourced assistance to help people ‘break the cycle’.

Size of the problem

Of the one million children in New Zealand, 90,000 have been the subject of a ‘report of concern’ to Child, Youth and Family (that’s 150,000 reports of concern a year). There are 50,000 investigations.

“When you look at the growth of reporting, it has grown four times in a decade,” says Dr Russell Wills.

“All that growth is in children witnessing family violence.”

Māori represent 25% of all children, but 50% of CYF children and 60% of children in care. The statistics say 55,000 children are resident in a home where the Police have been called because of violence; that’s one in 20 children. But it’s estimated that only one in every seven incidents is reported. “While there is a massive increase in referrals, there is still under-reporting,” explains Wills.

The largest rate of family violence is in the eastern regions – that’s Hawke’s Bay and Tairawhiti.

“Ours is the only region with an increase in family violence,” says Wills. “In other regions there are lower rates and they are dropping. We have the busiest Police and the busiest Child, Youth and Family.”

Detective Sergeant Daryl Moore is the coordinator of the Police’s Family Violence Team in Hawke’s Bay.

There are 5,500 FV incidents here a year, 15 every day; the figure has doubled in six years.

The increase in incidents is coupled with an increase in reporting, “The message is getting out there, but also the tolerance for family violence is lower. People don’t want to get involved but they will call,” says Moore.

The statistics once the family is ‘in the system’ are startling too. More that 60% have been referred before and on average they have been referred 4.5 times.

“We have a massive issue with people being seen again and again and not being sorted,” says Wills. “So we are seeing them, but we are not stopping the violence.”

Service providers

In Hawke’s Bay there are a range of services whose job is to work with children and their families involved in family violence, but each initiative is underfunded, reactionary, limited to restrictive contracts, silo-based and short term.

The individuals working within those services are pushing hard to fix these issues, they step over the line, involve themselves and find essential additional funding (for many services government funding is known as Contributive Funding; for example, Women’s Refuge receives 36% of what they need from Ministry of Social Development).

“If you are born into a stressful situation you are still making connections but they are different: gratification needs to be immediate, there’s a strong flight or fight reflex, there’s no trust. And that is hard-wired.” – Dr Russell Wills

Women’s Refuge is at the front line. Alongside the Police and DOVE (who predominantly work with perpetrators of family violence), Women’s Refuge appears early in the response. Close to 100 women use their safe-house service a year and 2,500 access their 24-hour help desk.

They run a 10-session programme for children involved in family violence, either as witness, victim or participant. This programme’s funding has recently been cut; only 15 spaces are available this year, with 56 in 2015.

Julie Hart, Hastings Women’s Refuge manager, explains the programme:

“It’s for kids who’ve been in a home where violence is happening and where parents have addressed the violence. There are very few services for child victims of family violence. Once they’ve become an off ender there are programmes through youth justice.”

All the children participating in Women’s Refuge-run programmes are there because their mothers (generally speaking) have accessed Refuge services. The Refuge is unable to take referrals from other agencies due to funding cuts.

“It’s a broad range of women who come: from the first time [the violence] happens through to ‘Last night I thought I was going to die’,” says Hart. “The children have often bear silent witness. They have no power of decision making, they don’t have resources, they have to rely on adults. Often, the kids are just forgotten.”

Hart explains that the array of children’s responses to what they’re experiencing is diverse.

“They can range from withdrawn and shy, to having no social boundaries, to kids who are ‘being the parents’ from as young as four. The most common thing is they are angry, frustrated and frightened.”

Julie Hart has worked within Women’s Refuge for 22 years. She says plans for proactive and positive programmes for young people are scuppered by lack of money.

“We keep putting our hope in MSD, but reality is showing us that it’s not going to happen,” says Hart. “We turn to philanthropics and socially-minded business groups.”

She says most programmes are limited. “There’s very little value put on victims of family violence.”

DOVE works with children too, but principally their work is with perpetrators. Malcolm Byford, DOVE general manager, explains: “We have two specific contracts working with children to help mitigate the impact on them and their future development.”

One programme is paid for by Ministry of Social Development; it’s a self-referral programme, available on a one-to-one or sibling group basis. The same programme is offered, through Ministry of Justice funding, to children who are the subject of a protection order.

Malcolm Byford feels there’s a big gap in programmes for young people generally, although there is funding available for children who are acting out.

“You’ve got to get bad enough to get funding to do some programmes,” explains Byford. “But the effect for some children is to become depressed and quiet. It’s a case of the squeaky wheel.”

“There is more thought going into working with children and their anger,” he says. “I’m not sure if the ones who are affected more inwardly get the help they need.”

At the top of the cliff

Another part of the puzzle is the agencies who offer programmes in parenting, and, through schools, work with vulnerable children. Groups like Family Works in Hastings and Birthright in Napier.

If CYF is the proverbial ambulance at the bottom of the hill, then Family Works is part of the fence at the top.

Rose Tweedie is a social worker by training and manager of Family Works, which is part of Presbyterian Support East Coast.

The children and families her team works with are referred from a variety of sources – paediatricians, schools, Police, parents, even the children themselves.

“It’s really difficult. We have had to put referrals on hold. Vulnerable children and families need to be seen quickly, not in six weeks.” – Rose Tweedie, Family Works

A key contract for Family Works is as a provider of Social Workers In Schools or ‘Swissies’. There are ten Family Works Swissies in deciles 1-3 schools in Hastings and CHB. Each works in a number of schools.

“The children know the Swissies. But they are thinly spread,” says Tweedie. The affinity the Swissies have with the children in their schools means they are often the first contact point for a child in need.

“There may be issues around truancy, inadequate clothing and food, aggression, changes in behaviour. Often there are multiple and complex needs and a whole box of problems.”

Swissies work with children at school, but also go into the home to complete an assessment that looks at the family’s strengths, needs and risks. This work can only happen if the parents give permission.

The number of children who would benefit from the work the Swissies do exceeds the ability of Family Works to meet the need.

“We’d love to be able to reduce the number of schools each Swissy looks after, and we could easily double the number of Swissies,” explains Tweedie.

Family Works does have other services including counselling, but the need is greater than the resources available.

Rose Tweedie: “It’s really difficult. We have had to put referrals on hold. Anything critical I take, but if there are options I refer on to other agencies. Vulnerable children and families need to be seen quickly, not in six weeks.”

The Family Works model means each family they take on has a key worker. Incidents of family violence are rarely isolated and often entangled with a suite of issues from mental health to truancy, to poverty and addiction. Having one person to call when things derail can mean the issue is sorted before it escalates. But that’s an expensive model and resourcing is thin.

“People forming a trust with you is important to keep continuity, they don’t want to tell their whole story again and again,” explains Tweedie, who says having the will to change within the family is key.

Breaking down those boundaries between the family and social services is a necessary, but challenging, fi rst step. “They can be reluctant to engage with professionals. Sometimes they have been let down by others and there can be a strong distrust of strangers. The most important thing is to get the family on side.”

Protection orders

Few social service providers can get involved in a family in any significant way without the family first agreeing. Often one catalyst for this is when a protection order is filed. This sets off court-sanctioned events than can facilitate a family agreeing to assistance.

When there has been an incident of family violence in a home, the victim can apply for a protection order. They then become ‘The Applicant’. The perpetrator of the violence is known as ‘The Respondent’.

There are two forms of protection order: On Notice and Without Notice. The latter is effective immediately and the respondent finds out about the order once it has already come into effect. This is seen by many agencies as the safest option for victims.

When an order is On Notice the respondent is warned it’s going to happen. There is a trend currently for the courts to decline applications for Without Notice orders in favour of On Notice.

Julie Hart from Women’s Refuge explains why this adds to the problem: “Women won’t do it then, because of what they see as the consequences of that. The protection order can become a danger element and the risk goes up.”

Respondents of protection orders must attend a compulsory sixteen week counselling course. DOVE runs these.

Child victims can access a short term programme if their caregiver applies for it; there’s no compulsory requirement.

Malcolm Byford agrees there is a gap for children who have witnessed violence in their home. Byford says although the course makes a positive immediate impact some respondents find changing lifetime habits difficult. Once the course is complete there’s limited facility to keep working with the perpetrators.

“We have no capacity to do follow up work,” he says. “We’d like to follow up or have a peer support programme like AA. They do make behavioural change but it’s hard to sustain.”

Child, Youth and Family

Central to many family violence situations, especially critical incidents, is the Ministry of Social Development’s Child, Youth and Family service (CYF).

CYF becomes part of the equation either when they’re contacted by an agency or a member of the public with a report of concern, or when the Police is called to

a family violence event where children are at immediate risk.

Currently CYF is undergoing a massive rethink by central government which hints at the situation within the service. Many of the people spoken to for this story shared a frustration with the agency.

Julie Hart, Women’s Refuge: “Individual CYF workers have great love and want to do the right thing but the system doesn’t fit that kaupapa.”

CYF replied to a request for an interview for this story with a written response from their media office in Wellington. This was followed up with a brief telephone interview with Donna MacNichol,manager of the service in Hawke’s Bay, under strict conditions from a CYF public relations adviser.

The CYF response to family violence focuses on involving the wider family. MacNichol explains CYF is a reactionary service involved in crisis situations rather than preventative or long-term solutions.

“We’re a child protection organisation first and foremost, we’re good at assessing safety. If there’s ongoing family violence that’s affecting safety, then we go in.”

CYF then relies on family, community and community-based services like DOVE and Family Works to pick up the need.

“Let’s say we find scary things going on, then we bring in the wider family and look at whether family members will step up and take [the children] on,” says MacNichol.

“It’s good to have family involved, even just in decision making. If they wish to be they can stay involved in decision-making even if they can’t take the child.”

CYF is notified of every incident of family violence. They will remove the child from the home only if there is immediate risk to that child. From there family is involved to look at what happens next.

Then community-based agencies step in. Long-term assistance for family violence victims and witnesses is non-existent.

CYF relies heavily on service providers, but MSD, of which CYF is a part, fails to fund them to any credible level. Also, providers are constrained in their practice by their contracts for service, which often stifl e a genuine, considered approach to creating solutions suited to the individual family.

Change ahead

One of the key issues with the system– within CYF and the support agencies – is the focus on the role of the victim. In many cases it is up to the victim to find the strength to get help; it’s seen as their responsibility to keep themselves safe.

Victims, most often women and their children, must actively seek protection through applying for protection orders. Programmes for children, whether run by Women’s Refuge, Family Works or DOVE, focus on preparing ‘safety plans’ identifying what to do, where to go or who to turn to when the proverbial hits the fan.

Malcolm Byford believes the whole system needs a mind shift. “You don’t want the responsibility of the victim’s safety to sit with them. If we’re asking them to keep themselves safe, that’s a very vulnerable situation to be in. That’s something that needs to be changed.”

Julie Hart says her programme for children does have a number of elements requiring the child to identify their safety plan, but programmes for perpetrators of violence are just as crucial.

“It takes work with the violent partner. The victim can’t do that. She doesn’t have the power to change that,” says Hart.

Future

Much work has been put into making the significant changes needed within the system for addressing family violence.

Paula Rebstock’s Modernising Child, Youth and Family report of a year ago kicked off a whole ‘about face’ for CYF. But seeing changes embed and begin to impact culture, society and the lives of individual families is a long way off and needs a lot of hard work.

The Police, Women’s Refuge and DOVE are three parts of the Family Violence Interagency Response System in Hawke’s Bay, which meets weekly to discuss incidents reported to the Police. This coordinated, wrap-around approach signals the type of change all those involved hope to see more of, but it needs appropriate resourcing.

Malcolm Byford, DOVE: “We are still fragmented. We need a system that integrates responses to family violence… we’ll make best progress when all components are working in a good joined-up way. We are attempting to do that now but with slim funding and it’s off our own backs. We need leadership around this stuff , from all levels.”

Many feel it’s vital to put in place pre-emptive programmes for pre-teens across all schools. Julie Hart at Women’s Refuge would like to see this made a priority; Malcolm Byford salutes the work of a few fledgling programmes that have started in schools already.

Daryl Moore of the Police agrees that starting young and working in a preventative way would help; “It’s about understanding power and control. We teach kids to read and write but not what they need to know in terms of healthy relationships and knowing what bad and good look like.”

He continues, “In the past there’s been lots of bandaids on lots of cracks, so there’s this real push for a whole new system. The current process is not working, it’s broken and it needs to change.”

Dr Russell Wills agrees that getting in early is the key. “The most cost effective way is to identify the family before the baby is born and wrap around that family and child while parents’ own trauma is addressed and nurtured, then put support in place through the birth and on.”

Currently Hawke’s Bay has a Maternal Wellbeing Programme, led by DHB, that loops in midwives and agencies. It’s the first in the country and so far there are high success rates. It’s a service focusing on specific women identified as vulnerable. About 20 women are discussed at each weekly meeting. Care continues until the baby is six weeks, but Wills says this will soon increase to two years old.

“Most parents want to change, most consent to receive help, most engage and most get better, which is an absolute joy,” says Wills.

Wills believes that multi-strand, robust training across the full ‘children’s workforce’ – 370,000 people in New Zealand – is necessary.

“Clinicians are trained in family violence or mental health or addiction, but clients have issues in all three,” explains Wills. “The better trained we are, the better skilled we are to have the difficult conversations, the better we are at having trusting relationships as professionals, the fewer people will fall through the gaps.”