This update is entirely about water. Some Hawke’s Bay issues – like water and the condition of our health care – simply require revisiting over and over because of their crucial significance to the overall wellbeing of our population.

We’re now spending millions on long-neglected water infrastructure, but can’t spend it fast enough or without significant cost overruns … and chafe at our rates.

We’re excited about storage schemes, but unwilling to embrace serious conservation measures that would curb consumption.

We’re thrilled to live by the sea, but nonchalant about dumping waste into it, whether intentionally (wastewater disposal) or accidentally (industrial discharge, stormwater).

We hyperventilate about water uses we find particularly galling (like exporting it in plastic bottles in pure versus adulterated form … think juice), but resist any regulatory attempts that might assign societal priorities to water use.

We want it safe and pure, but public health measures considered routine by some – like chlorination and fluoridation – are seen as toxic by others.

What is a poor councillor to do?! Here’s the state of play of the key water issues immediately challenging the region.

Water quality/safety

As much as we care about native fish, trout, macroinvertebrates and swimming in clean rivers, let’s begin by cutting to the chase … providing safe drinking water for humans.

Havelock North’s most enduring ‘gift’ to the nation was a gastro-disaster that triggered an overhaul of drinking water regulation, with a new operational and enforcement structure planned, and placed a spotlight of decades of malfeasance on the part of local councils throughout NZ who neglected their water infrastructure.

Later this year, a dedicated national regulator of the three waters, Taumata Arowai, will take over, a Crown agent empowered last year by enactment of the Water Services Regulator Act. Further clarification of responsibilities, for example regarding rural drinking water schemes, will be set out in a Water Services Bill later this year.

The functions of Taumata Arowai will be to:

• Oversee and administer, and enforce a new, expanded and strengthened drinking-water regulatory system, to ensure all New Zealand communities have access to safe drinking water, and if need be hold suppliers to account.

• Provide oversight of the regulation, management, and environmental performance of wastewater and storm-water networks, including promoting public understanding of that performance.

In the meantime, a government infrastructure review now underway at last count has estimated our defective water systems – drinking, waste and storm water – will require up to $46 billion to bring to First World standard … and maybe more.

Consistent with this, a study conducted for our region conservatively estimates that more like $605 million will be required to bring Hawke’s Bay’s ageing water systems up to modern standards in terms of safety, reliability and environmental performance.

So, between Havelock North-identified need, the preceding Labour-led Government’s broader urge to support the provinces (i.e., Provincial Growth Fund), and the subsequent flood of Covid recovery money, millions are now allocated for infrastructure upgrades ($50 million so far to Hawke’s Bay councils).

So much money that councils can’t find enough construction workers and materials to spend it on.

As BayBuzz has reported online, these millions are coming with significant shifts in political control.

In addition to creating Taumata Arowai, the Government is planning reorganisation of 3 Waters implementation, putting this spending and operational control in the hands of five or so pan-regional authorities.

The Department for Internal Affairs is analysing detailed information provided by each council in NZ to arrive at a more reliable – and sure to be higher – estimate of cost. Cabinet should be reviewing this bad news about now, and the final reorganisation plan is expected soon.

The Government has made clear it believes local councils have bungled their responsibility by failing to make the needed investments for decades. And moreover, that equity (every New Zealander deserves the same water safety) requires a different funding approach (i.e. rural residents in CHB shouldn’t have to pay grossly more for safe water than their cousins in Napier … and can’t afford to). While policy-makers ponder, we see disturbing headlines with regularity – a key water main bursts in Central Hawke’s Bay, cost overruns in Hastings for new drinking water infrastructure, and Wairoa at odds with the Regional Council over wastewater discharges.

So, while councils have been told they would have the opportunity, after consultation with their respective constituents, to opt out of this new governance scheme, who would dare do so?

Perhaps Napier, in its quest for chlorine free water. NCC’s recent review of options concluded it would take some 20 years and cost ‘only’ about $100 million more to be chlorine free than the $178 million required to build a fully health-compliant drinking water system, still using chlorine. A key caveat to these costs was the study’s observation that Napier had some 487 kilometres of antiquated underground piping, so the repair bill could easily climb.

And after all that, shutting off the chlorine would require a Government exemption.

Speaking of who’s calling the drinking water shots, it appears the fluoride debate is over. The Government has announced it is placing that call in the hands of the Director General of Health, the revered Dr Ashley Bloomfield. When the necessary Bill passes later this year, there’s little doubt what he will decide.

Water ecology

Meantime, the fate of our waterways in terms of healthy ecosystems sits in the hands of current (for the Tukituki catchment) and pending plan changes (for Heretaunga waterways, Mohaka) initiated by the Regional Council, but now needing to conform quickly to relatively tough national environmental standards.

The Tukituki rules are well into implementation; a second round of updated Farm Environmental Management Plans (FEMPs) were due at the end of May. In addition, some 150 CHB farmers in catchments with high nitrate levels were required to apply for farming (production land use) consents by 26 February, a first in the region. At last report, about 50 had done so.

On the Heretaunga Plains, it’s pretty much business as usual. The infamous TANK process, begun in 2012, filed its recommendations in 2018. This proposed Plan Change 9 got bogged down in HBRC’s Regional Planning Committee, and was not publicly notified until March 2020. Then came Covid delays. Finally, submissions on the Plan Change will commence 24 May and continue in June.

The waters were further muddied by a separate request from some environmental and Māori parties for a Water Conservation Order as an alternative means of protecting the Ngaruroro and Clive Rivers. The resulting process before a Special Tribunal essentially replayed the same evidence and arguments as examined by TANK. The Tribunal’s Order is now before the Environment Court, with a hearing set for 14 June.

So the wheels turn slowly and the waterways of the Heretaunga Plains await their environmental rescue.

A key issue that all parties seem to agree must be addressed is soil erosion, causing severe downstream sedimentation in the catchment. While rule-making is stalled, the Regional Council has embarked on a major $30m programme (region-wide) of erosion protection via fencing and planting. So far, $4.3m of this funding (with farmer matching) has been spent for on-farm improvements, with more committed.

And, as a band-aid, to deal with the sedimentation of the Clive River, HBRC is presently consulting on a recommended $2.8 million dredging proposal.

Down in CHB in the upper Tukituki, gravel build-up is the problem, in this case a natural not man-made phenomenon. Climate change induced high rainfalls could exacerbate the gravel build-up and combined with higher rain volume itself increase the flooding risk to Waipawa and Waipukurau. HBRC is presently consulting on a recommended $2.54 million gravel extraction proposal that would match $4.51 million from Government.

In Napier, the prime water quality issue centers in the Ahuriri Estuary, which with regularity is violated by illegal industrial discharges and stormwater overflows. NCC is stiffening its by-laws regarding run-off from the Pandora area, and violators occasionally get prosecuted; however, resolution of the stormwater pollution unfortunately awaits the multi-year programme of infrastructure upgrades.

It’s hard to see what a $20 million plan to create a Ahuriri Regional Park, as presently proposed in NCC and HBRC pending LTPs, can achieve until known pollution sources are seriously dealt with. Important to that goal will be the ambitious new Marine Cultural Health Programme to be led and implemented by marae and hapū of Ahuriri, supported by Napier Port.

Heading north, a bit of good news recently when HBRC lifted its health warning against swimming in Lake Tutira. However, farther up the road, Wairoa wastewater discharges into the Wairoa River, and associated consents, are an ongoing matter of dispute (two years now) between WDC and the Regional Council. Meantime, the discharges continue.

Water use/availability

As tough as the water quality issues are, water supply issues are even more politically fraught, as here we find competing users and economic interests determined to duel over limited – and perhaps diminishing supplies.

Surprising as it might be, as the region argues over dams, aquifer recharge, irrigation takes and bans, summer municipal water restrictions, and exporting water, we still lack a definitive assessment of the region’s projected water demand and supply.

The water supply (or security) issue has centered on CHB and the Heretaunga Plains.

Starting with the latter, ‘best information’ at the time of the TANK review suggested that the Heretaunga aquifer was in delicate balance, at about 100 million cubic metres of water used annually, and in danger of being ‘mined’ beyond its recharge potential. With, surprisingly, no opposition from commercial and municipal water users, a ban was placed on any new water consents. The legal basis for such a ban is questionable, but it has been observed. A victory, one would think, for the environment.

However, when modeling suggested users could reduce their use by another 10 million or so cubic metres a year, and Māori sought to have that lower ‘cap’ written into the TANK Plan, a political impasse ensued. At the same time, an estimate was produced suggesting the mid-term annual gap between supply and demand might be around 5-10 million cubes, not a huge number in the scheme of things. Which raises the question of whether saving water might be a better (or initial) strategy instead of harvesting and storing more. And indeed the TANK Plan specifically barred any dams on the Ngaruroro River and its key tributaries.

So that’s where matters stood, putting mighty pressure on HBRC to come up with a more rigorous assessment of present and future water needs.

Consequently, a formal Regional Water Assessment has been underway since 2019. As stated in a HBRC paper, here is the philosophy guiding it:

“If developed in isolation, water storage has proven to be a complex and divisive endeavour … and gives rise to fears that water storage only delivers ‘more of the same’. However if developed as part of a package of solutions, storage can and should rightly be included in the use of the region’s freshwater over the next 30-50 years.”

At the same time, the PGF – full of coin and in the building business – came along and was awarded $11.2 million for investigating water storage options on the Heretaunga Plains. Eagerly sought by HBRC, fresh questions were raised as to whether storage once again won the inside track over savings.

So now the HBRC is pushing hard to complete its water assessment (aiming for spring), diligently quantifying ‘accounts’ for all water uses, present and future, while also consulting in its proposed LTP on spending $1 million to investigate non-storage options and their potential for filling some part of the expected gap the assessment will more reliably establish between long-term supply and demand. In this context, such options include water conservation, efficiency measures, farm systems and land-use change, allocation policies, and recycling and re-using water Common sense and smart politics are aligned on this enlightened approach!

While the ‘savings’ side of the equation unfolds, leading the pack as a water ‘supply’ option for the Heretaunga Plains, with fresh money ($5m) allocated for feasibility study by Government, is a proposal to expand an existing private lake. Using harvested high flow waters from the Ngaruroro, it would provide greater water flow for depleted streams in the Bridge Pā area, ultimately feeding into the Karamū Stream.

The concept was initially developed at his own expense by owner of the lake, Mike Glazebrook, and was first mooted during the TANK process. At the time, all the relevant parties in the TANK process — environmentalists, Māori, water users, council planners — visited the site, heard the case, kicked the tyres and, it appeared, were positively inclined toward it.

The scheme would store water at little incremental cost, and release it into lowland streams typically depleted in summer, a significant environmental gain.

Now, however, with some Māori and environmentalists digging in against water storage, we’ll see if the ground has shifted.

Down in Central Hawke’s Bay, the original epicentre of dam controversy, the waters seems calmer.

Efforts to revive the original Ruataniwha Dam have failed, and a Tonkin+Taylor review of other smaller scale storage sites offered little prospect. The Regional Council closed (or parked?) the matter, passing this resolution:

“Council acknowledges that staff will not progress, at this stage, a business case for pre-feasibility for above ground water storage sites, but will progress cost and benefit assessment of smaller scale storage and the Managed Aquifer Recharge Pilot Study.”

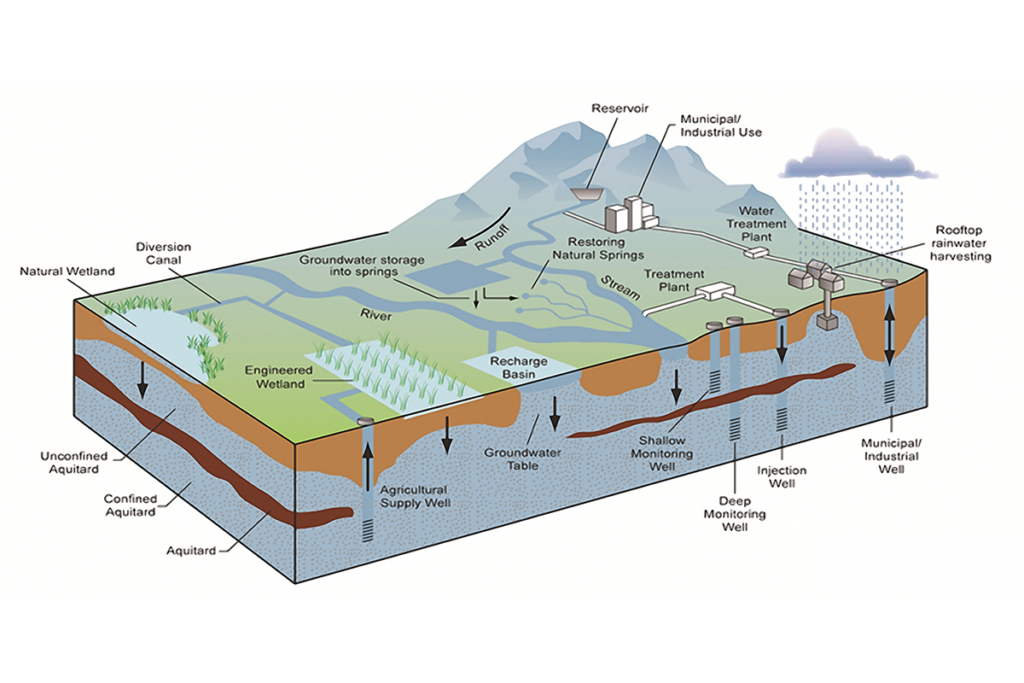

So, sitting on another $14.7 million of PGF ‘water storage options’ funding, HBRC has moved on to Managed Aquifer Recharge, or MAR. The concept is simple: harvest high quality river and stream water during high winter flows, settle and filter that water, and then recharge it into the aquifers below the Ruataniwha Plains.

MAR is widely used in other parts of the world and is being trialled in Gisborne and the Hekeao/Hinds catchment of Canterbury. The pilot project to which HBRC is committed in CHB will probably use two approaches: shallow recharge using a wetland and recharge basin system, and deeper aquifer recharge using an injection well system.

A potential site has been tested and appropriate pre-consultations and negotiations are underway. Consents would be required, affording opportunity for public comment.

Once a site is up and running, the pilot would be run for twelve months. If all goes to plan, the first data from the scheme would be available by the end of 2022.

Lots of fingers crossed on that one!

What vision for HB?

HBRC chairman Rex Graham recently wrote:

“As climate change and a growing economy places increasing pressure on freshwater, all levers must be pulled to secure fairer access to freshwater and protect our streams while protecting the Hawke’s Bay economy.”

Not everyone will agree that continued intensive use of our water resource to benefit economic activity can co-exist in Hawke’s Bay with a safe, sustainable environment.

From the Māori perspective, we are simply over-exploiting and depleting the natural ecosystem when protecting that ecosystem must be our paramount responsibility. Interventions like MAR and water harvesting are merely band-aids that futilely seek to cover the wound, while continuing the source of the injury.

However, Chairman Graham further writes: “Having built two cities, major export industries and world leading horticulture on this water resource, the economic and social effect of pulling the water ‘rug’ out from our community is simply not an option and we will not do this.” At bottom, that’s a statement that economic growth rules over all.

Many in Hawke’s Bay would not subscribe to that view; the more optimistic probably hope that trade-off can be averted. So it is understandable that the Regional Council is pursuing a path that aspires to ‘do good and do well’.

At this point, I believe the Council is proceeding – with broad support from most other political leaders in the region – prudently, transparently and fairly.

And BayBuzz readers know I wouldn’t hesitate to say otherwise if I didn’t believe so!

Brilliant, just two missing items:

the analysis of the projected frequency of overtopping of stopbanks

and

the implications of sea level rise for Hawke’s Bay surface water flows?

Also, No mention of management effects on soil carbon and water cycle in the wider catchment.

Each additional 1% in the top 150mm soil Carbon will store an additional 144,000l of water (give or take depending on other variables). NZ is not as carbon saturated as espoused.

Effective rain is the proportion of the total that infiltrates. Only soils with active fungal activity can build the necessary architecture for both air and water to infiltrate. Ineffective water cycles are not fixed by pouring more on with an irrigator.

Water cycles cannot repair without paying attention to all other ecosystem processes. These are solar cycle, mineral cycle and community dynamics (diversity) as they are all perspectives of overall ecological health.

All the above is either increasing in health and vitality or degrading, rarely static, and totally dependent on management.

Malcolm White is right. The answer to the water availability issue is in the soil. This should be combined with nature-based solutions like riparian planting, wetland restoration, detainment bunds, swales and leaky dams to slow water down. Streams and rivers should be wider and with more natural character. All of these measures can work at scale over the whole of a catchment and provide the added benefits of increased biodiversity and improvements in water quality.